Pitt football pioneer Bobby Grier honored at History Center program

On Jan. 2, 1956, college football fans gathered at Tulane Stadium in New Orleans. They were there to watch the annual Sugar Bowl, played between the University of Pittsburgh Panthers and the Georgia Tech Yellow Jackets, but they also got to witness history.

It was the first ever racially integrated Sugar Bowl, a feat achieved thanks to the inclusion of University of Pittsburgh Panther Bobby Grier, a Black player who changed the game.

The Western Pennsylvania Sports Museum at the Heinz History Center in the Strip District honored and explored the legacy of the Pitt legend on Wednesday night with its program “Game Changers: Bobby Grier.”

A panel discussion featured a slate of historians, football players and people close to Grier. Included were Samuel W. Black, director of the African American Program at the Heinz History Center; Rob Ruck, a sports historian and University of Pittsburgh professor; Rob Grier Jr., son of Bobby Grier; Dorin Dickerson, a former All-American tight end at the University of Pittsburgh; and Brandon Miree, a former standout running back at the University of Pittsburgh.

Also in attendance were Bob Rosborough, another member of that 1955 Pitt football team, and the family of John Cenci, a co-captain of the 1955 Pitt Panthers.

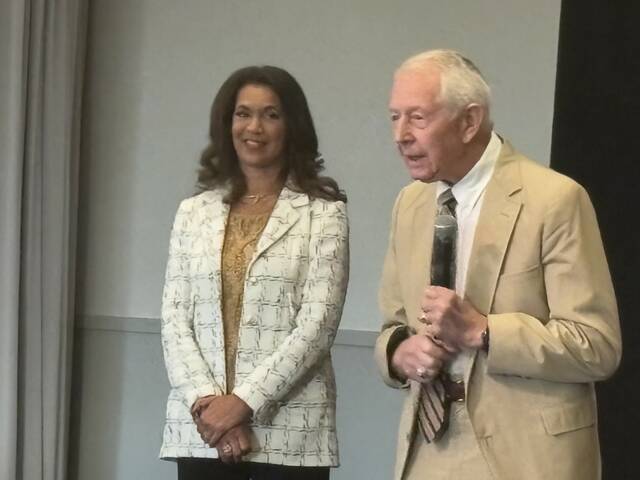

Award-winning CNN anchor Fredricka Whitfield moderated the discussion.

“On behalf of my family, I want to thank you for being here tonight. It is deeply humbling to stand in this space and celebrate the legend of my dad,” Grier said in an introduction. “He was a man of quiet courage and grace who wanted to answer history’s call with dignity.”

Throughout the nearly two-hour conversation, panelists and other attendees shared the story of the Pitt Panthers team and their journey to the Sugar Bowl. They began with some historical context.

Samuel W. Black looked at eight years before and eight years after the game. He cited events, including Jackie Robinson becoming the first Black player in modern Major League Baseball and the Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision, to provide context.

“Most or many of the Northern colleges and universities had integrated sports,” he said. “It wasn’t until 1970, roughly, that you began to see integration in Southern major college football.”

During the 1955 season, several major events occurred in the American South, including the lynching of 14-year-old Emmett Till in Mississippi and his murderers’ subsequent acquittal; and Rosa Parks’ refusal to give up her bus seat, sparking the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

“All of this was surrounding this historic occasion of Bobby Grier being on that Pitt football team,” Black said.

Ruck added to that sense of time.

“The University of Pittsburgh had Black students since the 1890s or early 1900s. … You don’t have a lot of Black players, and that’s the same thing for professional teams in Pittsburgh,” he said.

He theorized that the spotlight shone on Grier changed and opened minds at the time. “I think people are less defensive about racial change in sport, because they assume it’s a level playing field, and everybody should have a right to compete.”

He also pointed out that in the lead-up to the 1956 Sugar Bowl, the segregationist governor of Georgia, Marvin Griffin, released a statement saying in part that “the South stands at Armageddon” and “we cannot make the slightest concession to the enemy in this dark and lamentable hour of struggle.”

As a result of his statement, Ruck said, thousands of students at colleges and universities across Georgia broke into vehement protest against Griffin. “The governor, in all his racist stupidity, provoked, I think, a response that changed minds.”

Whitfield added that the governor sent a telegram to the Georgia Board of Regents to demand that the teams in the state university system not participate in events where Blacks and whites would compete against each other.

“But those Georgia Tech students, they protested,” he said. “And that says a lot, too, because we’re talking about the heart of Pitt and Pitt’s football team, but it also showed that there was heart that was on display.”

“You know, Dad kind of felt guilty, because all the spotlight was on him,” Grier said.

Rosborough stepped up to tell the story of the team meeting that came after Griffin’s attempts to stop Pitt from playing against Georgia Tech in the Sugar Bowl.

“Pitt decided to ask the head coach to call a meeting of the team, and to let the Pitt football team make the decision,” he said. “But we didn’t know that. … The Pitt football team was called for a meeting in Pitt Stadium.”

He said that coach John Michelosen stood up and told the team that they had a bid for the Sugar Bowl. “He said, ‘The good news for you is this: you’re going to decide today whether or not Pitt accepts that bid to play in the game. That’s why you’re here. But, there’s a problem.’”

He explained the circumstances. “If we accept this bid, there could be problems. So if we accept this bid, it might mean that we lose the bid or maybe we won’t be playing with our teammate, Bobby Grier.”

The coaches left the room and let the team decide.

“Guess what happened? Who’s sitting in the middle of the room? Bobby Grier. … Bob said, ‘fellas, I want you to know I want to play in that game with everything in my heart. I’m looking forward to it. But if it means that you can’t play in it, or if it means that there’s all kinds of problems, I guess what I’ll do is just bow out.’”

“That was the nature of my teammate,” Rosborough added.

That’s not what happened.

“We decided as a team that we wanted to do the same thing. We wanted to play in this game together. … If Bob couldn’t play with us, we wouldn’t play in the game, and we voted to accept the bid and to play in it as a united team, white players and one Black player.”

The next day, the coach alerted the administration about the team’s decision, and a telegram was sent to Griffin and the Sugar Bowl committee. The telegram said, “No Grier, no game.”

The son-in-law of John Cenci, who was the co-captain of that Panthers football team, read his father-in-law’s words. “Bobby was my friend, my good friend,” he read. “It was a privilege to be Bobby’s teammate.”

“Bobby had pride in himself and in the team. He was always a gentleman. … We didn’t think of Bobby playing as breaking the color barrier, but just as a group of men who had worked together for the same goal, striving to achieve that goal together.”

Pitt did not come out of that game victorious — they lost 0-7, the only touchdown for Georgia Tech coming after a questionable pass interference call against Grier — but there were still highlights for the first Black player to play in a Sugar Bowl. He led both team running backs with 51 yards.

Grier stayed on Tulane University’s campus during the events of the Sugar Bowl.

“He said that he had a really good time because obviously he couldn’t stay with his team; he did stay at Tulane. And they took him around and they had parties for him,” Grier said.

There was a banquet after the game, and the Georgia Tech team ate with Grier, which Grier said was a meaningful memory for his father.

Growing up, Grier wasn’t always aware of his father’s fame or impact, even when they attended Pitt football games and Grier was asked for autographs.

“I was always proud of him and just thankful, because he was so humble and just a great father.”

Grier is in the Sugar Bowl Hall of Fame and the Pitt Athletics Hall of Fame. He graduated from Pitt in 1957 with a bachelor’s degree in business administration, then joined the Air Force. In his post-military career, he was a supervisor at U.S. Steel and an administrator at the Community College of Allegheny County. Grier passed away in June 2024.

“He saw himself as a father, that’s what he saw himself as,” Grier said. “He didn’t see himself as like Martin Luther King or somebody who was at the forefront of the Civil Rights Movement. But he did know that what the team did was very important, and he didn’t realize how important it was, but people would remind him.”

Dickerson reflected on how powerful the legacies of both Grier and his teammates are for future generations. “That’s why football is the greatest sport on Earth, because everybody has to be one.”

Miree talked about seeing Grier as a trailblazer who has opened the door to opportunities for players like him.

“By doing what you guys did, you gave me more options. … I think, to me, when the collective group of people get together and decide to do the right thing, that’s when society operates at its finest.”

Alexis Papalia is a TribLive staff writer. She can be reached at apapalia@triblive.com.

Remove the ads from your TribLIVE reading experience but still support the journalists who create the content with TribLIVE Ad-Free.