The music industry has been turned on its head since James McMurtry released his first album, “Too Long in the Wasteland,” back in 1989.

“The business model at that time was you would tour to support record sales in the hopes that you would sell enough records to live off the royalties. That never happened for me. I didn’t sell enough records,” McMurtry said recently from his home in Texas. “So very quickly it got to where the road had to provide revenue. So we had to tour it. We had to tour it cheap. We had to scale it down. And we learned to do that.”

That paid off when Napster came along in the early 2000s and continued as musical preferences shifted to streaming services over physical media.

“The royalties for digital media are next to nothing. So you can’t really hope to make it on that. You got to profit off the road,” he said. “And we already knew how by the time everything switched around. So we’re still doing this, just four guys in a van most of the time. We are a band and crew. At the end of the show, we put on our crew clothes and start loading (stuff).”

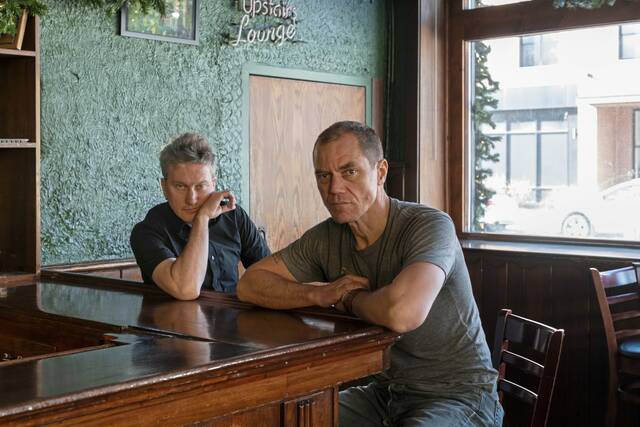

The acclaimed singer/songwriter will bring that approach to a free show on Aug. 16 at the South Park Amphitheater as part of the Allegheny County Summer Concert Series.

In recent years, McMurtry has made regular appearances at Club Cafe in Pittsburgh, noting he missed Rosebud in the Strip District and a now-closed Indian restaurant in the Days Inn on Banksville Road.

Although he’ll be flying in to Pittsburgh for this show and another in Buffalo, it sounds like he’d prefer to be in a van.

”I hate flying. Absolutely hate flying. And it’s gotten worse and worse,” said McMurtry, who acts as his own travel agent. “I think it’s getting where you almost can’t carry a guitar on, because you’ve got to find the TSA line that allows oversized. You’ve got to get in line behind all the people with strollers and whatever else to go through the scanner.

“And then you’ve got baggage fees that we didn’t use to have. In the ‘80s, it was easy to fly. You could fly a whole drum kit, just bribe the sky cap and get it on the plane.”

His most recent album, “The Horses and the Hounds,” came out in 2021, with “Canola Fields” being nominated for Song of the Year by the Americana Music Association.

McMurtry touched on his place in the music world today, the Americana label, putting his beliefs (or leaving them out) in a song and his new album:

Where do you think you fit into the music world today? Do you feel like there’s a spot for you?

I just did a sold-out tour. We’re doing great now. I think part of it though, I looked at the crowd one day and was wondering why we used to, we generally always sold out on the weekends and we kind of struggled through the week. Now we’re selling out all week long. And I finally figured out that, you know, I’m 62. And the median age of the crowd is about my age. There’s some younger people, some older, but a lot of them are retired, so they can go out all week long. They don’t have to clock in in the morning.

They can go out and have a good time and don’t have anything to worry about the next day.

Ray Wylie Hubbard said it’s the night people’s job to get the day people’s money, so that’s what we do.

Do you think that your music qualifies as Americana? Is that label OK with you?

I don’t really care about labels. If it helps sell, it’s fine. And Americana, when it started, it seemed to be another word for scruffy white guys with guitars. Now it has expanded. The last AMA award show I went to was really pretty cool. Brandi Carlile was ruling the roost, and we had a lot of women artists, a lot of black artists, gay artists, straight artists, everything. It was like, it finally opened up.

When you look at the current state of the country, does that give you a lot of material to write about?

I don’t know. I don’t pick any set type of material to write about. I get a couple of words and a melody, and I follow it wherever it leads. And I try to stay true to the character that I hear singing it. And a lot of times, the character would not agree with me if that character were real.

So it’s not just your personal feelings and beliefs coming out in these songs?

It can’t be because if you do that, you’re going to write a sermon. Every now and then you can get away with it. Steve Earle does a really great job of getting his point across through his characters. But you can’t break character in the song, or you’ll lose the song. It’ll be less effective. And so I’ve got a song called “Carlisle’s Haul.” It’s written from the point of view of a kid growing up in a commercial fishing town where everybody’s cracking about government regulation over fisheries. Well, I happen to believe we need those regulations if we’re going to have fish. But I’m not trying to pull my livelihood out of a bay or the ocean. So I can understand how somebody that does that might think differently. And there’s also a certain amount of group think that goes on. You know, if you have other thoughts, a lot of times you can’t reveal them because you’ll be ostracized. So I didn’t break character in that song. And it’s a pretty good song.

It’s interesting because a lot of people, they have one political opinion and they can’t bother to see the other side. And it doesn’t sound like that’s the case with you.

Well, I mean, I can sort of see the other side. I might not respect you. I certainly don’t agree with it a lot of times. But my job is to write the best song possible. So a lot of times I’ll have to look past my own point of view. And you have to give the song its head. You don’t want to rate it and regulate it too much. It’ll get boring if you do.

Related

• Interview: Former Ultravox frontman Midge Ure brings Band in a Box tour to Pittsburgh• Review: Sleater-Kinney shakes off vocal woes in Pittsburgh stop of Little Rope tour

• 2024 Pittsburgh area concert calendar

Have you noticed any blowback from making political statements with your songs or wearing the dress (in 2023 in Nashville)?

Certainly. Years ago I put out “We Can’t Make It Here,” and a lot of people took it as an anti-Bush song, which it was really anti-outsourcing and I started writing it during the Clinton administration. But I didn’t finish until (George W.) Bush was in. Didn’t really matter who was president, I didn’t think, but I remember somebody booing us when we started that song at a show in San Antonio. And he didn’t realize he was surrounded by a bunch of Veterans for Peace, which was an organization and they shouted him down pretty quick. But yeah, of course it happened, but I mean you gotta be willing to (tick) people off or you’re not making any kind of art. To put it most simply, I’ve said it before: it’s not our job to be loved, it’s our job to be remembered.

Back in 1989, John Mellencamp said that you write like you’ve lived a lifetime. Do you feel like a better songwriter now that you have even more life experience?

Certainly, the main thing that improved my songwriting was taking voice lessons, which I did not to try to be Pavarotti, but just to keep from losing my voice on the third gig out of every tour. … So I went to Mady Kaye, who’s a great Austin voice coach, and one of the things she taught me is you’re writing for an instrument. The voice is an instrument. It’s not like poetry where you can read it or it can be spoken. You have to sing those words, and so you want to write words that sing well. You don’t want to do weird vowels and diphthongs that will tongue-tie you. And so when I started writing for the voice, my songs got better.

It was six years in between “Complicated Game” and “The Horses and the Hounds.” Do you think there’ll be more new music (soon)?

I’ve got most of the new record in the can right now. The thing about “Horses,” we tracked that before the pandemic. We tracked it in 2019 and had most of the overdubs done that fall. We had some keyboards left to do in the spring. We had a session booked, and California shut down. So we had to do all the keyboard kind of piecemeal over, like having tracks emailed in from various places. And so it took a while to mix, and then they didn’t want to release it until we could tour. So there was a couple of years between the recording of that record and the release, which had happened a couple of times. Early on, my second record was shelved for two years after it was made, which is where I learned that there’s no such thing as a release date until after it happens.