If James McMurtry doesn’t make it to Pittsburgh for his show next week, he already has a sneaking suspicion where he’ll be.

“Hopefully they’ll let us back in from Canada the night before because we got to hop up to Toronto and do a date,” he said. “If we don’t get there, we’re probably at the border.”

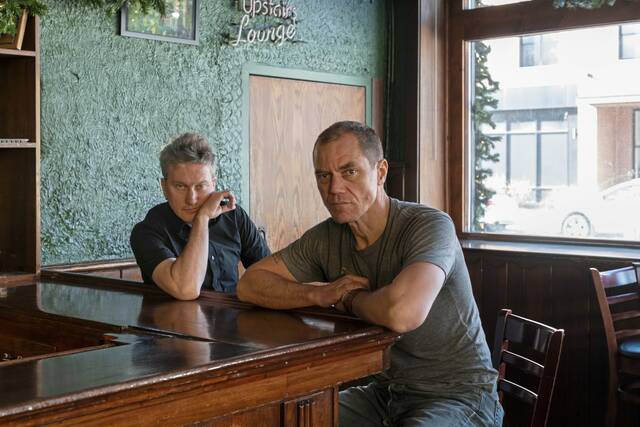

The singer-songwriter hits Pittsburgh with BettySoo opening for a Sept. 17 show at Thunderbird Music Hall in Lawrenceville, a day after a show at Toronto’s Horseshoe Tavern. Frequent touring by the 63-year-old allows him to soak in the country.

“I like seeing the world through the windshield and seeing what crops are growing this year, what the country looks like, because I can usually remember how it looked last year,” he said. “The rainfall patterns are different. Every now and then, we get on a new stretch of highway that we haven’t been across a million times. That’s always nice.”

The touring also creates some striking memories, like when McMurtry was in Los Angeles “two days after the so-called riot” in June.

“The Angelenos told me it consisted of about 200 people and they sent in the National Guard and the Marines. We were staying on Olympic about two blocks west of the 210 freeway, and I got an alert on my phone that said curfew for downtown L.A. from 8 p.m to 6 a.m the next morning,” he recalled. “I looked at the map and the curfew zone starts at the 210 – we’re two blocks west of the curfew zone and after the second day, BettySoo and I had to get up and leave at 5:30 in the morning to go up to Santa Cruz to do radio.

“The quickest way out was up the 210, but that’s in the curfew zone and I’m traveling with an Asian woman and ICE doesn’t care if you were born in Albany, New York, and raised in Houston, so we went up surface streets, took about an extra 20 minutes getting out of town.”

McMurtry, the son of the late author Larry McMurtry, is currently touring in support of his latest album, “The Black Dog and the Wandering Boy,” which featured guest appearances from Sarah Jarosz, Charlie Sexton and more.

In an August call from Lockhart, Texas, McMurtry spoke with TribLive about point of view in his songs, Weird Al Yankovic, why he writes and more. Find a transcript of the conversation, edited for clarity and length, below.

What’s the mood in Texas with all the redistricting controversies, the battles between Abbott, Newsom, all the border stuff? What’s the mood like down there?

Basically unchanged. That’s just how Texas is.

Does that real-life drama help to provide songwriting fuel for you?

No, not really. I write a song, but it’s just following the words. I hear a couple of lines and a melody in my head, and if it keeps me up, then I’ll keep working on it. When I build a song, it’s not really related to anything that’s going on. It can be, but mostly I write songs so I can make records so I can keep touring.

Would you describe yourself as an activist or a political songwriter at all?

Some of the songs I write have political overtones, and I don’t try to keep politics out of my music because politics is part of life. Music is part of life, and, yeah, I’ll make a point when I can. The thing about songs though: most of my songs are written from the point of view of fictional characters who may or may not agree with me. I have to be careful. My main job is to write a good song, and that means if I’m starting with a fictional character, I have to stay in character. If I try to inject an opinion that that character doesn’t agree with and I break character, then I have a sermon, not a song, and nobody wants to listen to it. There are instances where I can kind of get the point across. Steve Earle is brilliant at that. He can really write a political song that says what he wants to say without breaking character. I’m OK at it.

After listening to a song like “Annie,” it doesn’t sound like the song’s narrator is a big fan of President George W. Bush.

Well, of course, Annie refers to Ann Compton, who was a reporter for ABC News, who was on Air Force One when all that was going on. She was covering Bush’s educational promo tour that happened and was there in Florida when he had the children’s book and suddenly something happened and they all got herded back onto the airplane and flew around and finally touched down in Nebraska. And she called Peter Jennings live on the air. And that was his line. He said, “Annie.” She said, “Can you hear me?” He said, “Yes, I can hear you, Annie. What are you doing in Nebraska?” So that’s where I took that line from.

How do you find those references? Obviously, that’s 24 years ago. Does something like that just stuck in your mind and pop up randomly later?

I read it; there was some writeup or something a year or two later. I didn’t hear that live on the air or see it, but it got written up. You can look it up on the internet now, just Google Ann Compton. They still have that clip of Peter Jennings when everybody was just trying to figure out what was going on. And it’s like, American songwriters are required to come up with their We Will Never Forget 9-11 songs. And one of the things I’ll never forget about that day was that we heard from Yasser Arafat before we heard from our own president. And then yet he gets built up as a war hero later on. You know, that’s the power of spin.

With the song “Sons of the Second Sons,” that perspective also might sound like a criticism, to me, of where the U.S. is now.

This also just injects a little bit of history because a lot of what happened here had to do with European primogeniture. If a rich guy died, his oldest son got everything. Everybody else just sort of cut loose. They might have a little money. So a lot of them came over here and became industrialists and started on the pattern of slavery and genocide that led to the modern United States. It’s not just now I’m talking about.

Of all the references you could pull from, where did the Weird Al (Yankovic) one come from in “The Black Dog and the Wandering Boy”?

He did a parody of (Queen’s) “Another One Bites the Dust” called “Another One Rides the Bus,” (sings) “Another one’s on, and another one’s on” – that’s where I took the line. I thought I better footnote it so he didn’t sue me.

Are you a big Weird Al fan?

Weird Al was in the air when I was growing up. I would love to get big enough to get a Weird Al parody. That would mean I made it. (laughs)

I wanted to ask about the line “I can’t stand getting old. It don’t fit me” from “South Texas Lawman” – does that strike close to home to you?

That I took from one of my father’s books, that’s the Sam the Lion character in “The Last Picture Show.” It’s not in the movie, but there’s a scene – the scene’s in the movie but the line’s not there – where they’re out fishing and Sam is remembering his younger days and he just screams out, with an expletive that FCC won’t like, but he goes off, “I don’t want to be old. It don’t fit me. No, it don’t suit me,” but that’s where I took it. I wouldn’t have put it that way, but my father passed away not too long ago, a couple of years back, and that’s just a line that stuck with me.

The chorus of “Pinocchio in Vegas,” it seemed like it was reflecting on memories that are lost, grandmother’s friends and neighbors next door, so do you find yourself thinking more about the past these days?

One of the things that’s happened over the years is all three of my bandmates lost their fathers while traveling with me in the van. And one of them came back and said, I just realized, if I got questions about the neighbors that lived down the street when I was four years old, there’s nobody to call up and ask anymore. You lose somebody, then you lose a lot of access to information, because there’s stuff that only they know.

Related

• 2024: James McMurtry on scaled-down touring, Americana and more ahead of free Pittsburgh show

• Q&A: Superchunk’s Mac McCaughan on the band’s long-awaited return to Pittsburgh and more

• 2025 Pittsburgh area concert calendar

With this new album, what was the process like for creating it? I know you worked with producer Don Dixon, who you worked with before.

The process is, I make a record when my tour draw starts falling off because the main commercial plus to a record nowadays is I put it out and you guys will talk about it and write about it, and then people will know I’m coming to town and hopefully buy some tickets because all our revenue comes off the road now. Streaming royalties are nothing, and downloads aren’t much better. So we got to have some buzz, and so it was time to make a record. There was a while there in the past where I was producing my own record because nobody else really wanted to, and I’ve learned a lot from the producers that I worked with before.

I came to a point where I sort of just used up all their tricks and was repeating myself methodically, so I brought in C.C. Adcock for the “Complicated Game” record. Then I went with Ross Hogarth for “The Horses and the Hounds.” He had engineered my first couple of records for (John) Mellencamp and then I just thought, well, I’ll revisit Mr. Dixon’s homeroom because my style of producing I pretty much took from him and Lloyd Maines and Mellencamp to a certain extent. They were all good live producers. What Don is really good at is knowing when the good take is happening while it’s happening. If I’m producing myself, I can’t really tell while I’m trying to play and produce at the same time, so we’ll do three takes then we’ll go listen to them and see which one has the most life and then we’ll overdub on that one. With Dixon, he can tell and you finish the take and he’ll just say stay right there, punch the ending, punch that little spot there and then you got it. That saves me the 15 minutes of listening I would have had to do to listen to three takes on my own, and you’ve only got so much time in a day and you’re paying for that time. That smooths things out a lot.

You said the drive to make new music is based purely on touring, but are you always in writing mode? Are you always writing, maybe just not recording?

I might be turning lyrics over in my head, but I don’t really get into writing mode until it’s time to finish songs, and then I usually get a couple more in the studio because of the adrenaline of having to get it down generates lyrics that I wouldn’t otherwise have. The one on this record, “Back to Coeur d’Alene,” that’s the song that this session generated, it just kind of fell together. I just followed the words until it made a story.