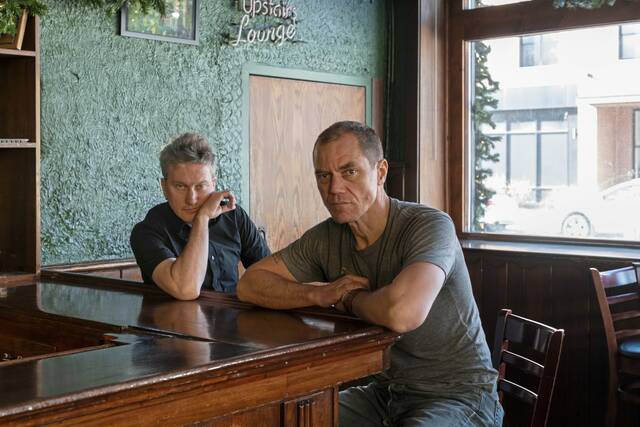

It might feel like Colin Hay is taking the first part of the title of his latest album, “Man @ Work Volume 2,” a bit too literally.

There were a pair of tours playing in Ringo Starr & His All-Starr Band earlier this year, plus Men at Work’s summer package tour with Toto and Christopher Cross, which visited the Pavilion at Star Lake on July 24.

Now, he’s in the midst of An Evening with Colin Hay solo tour, with a stop on Nov. 4 at the Carnegie of Homestead Music Hall.

“It’s just the way it’s worked out this year, a lot of touring,” Hay, 72, said earlier this month. “I think I still have a problem saying no.”

A native of Scotland, Hay first made his name in the 1980s with Australia’s Men At Work, with songs like “Down Under,” “Who Can It Be Now?” and “Overkill.” After the band’s breakup in 1986, Hay launched his solo career, with 16 studio albums. His latest, May’s “Man @ Work Volume 2,” includes new takes on songs from Men At Work and his solo career, as well as a new song, “We the People.”

In a Zoom conversation from California, Hay spoke with TribLive about his solo show, Men At Work’s demise, Ringo Starr and more. Find a transcript of the conversation, edited for clarity and length, below.

How do you view those solo shows versus the bigger package tours? Do you have a preference on which one you like better?

They’re just very different. I have a particular love of the solo touring because when I was dropped, I think it was 1991, by MCA Records, I didn’t really know what to do. There was no label or agents or anything like that, so I just went out on the road and played shows and just developed this touring life, which was quite under the radar so to speak and just building an audience from square one really. It’s still building, so that’s really what the solo thing is and people just come along and they they tell other people. It’s not based on any kind of high degree of anything really except people just come along to the show, so it has its own rewards in that sense, and it’s quite quite nourishing. The package tour with Toto was really great because Steve Lukather is a friend of mine, and I know Christopher Cross a little bit, and on the music, there were overlaps stylistically, so it worked really well and it was a lot of fun to do. I love traveling with this band — we travel really well together — so it was a different kind of fun doing that tour, so I don’t really have a preference. They’re just different, but as far as on a personal level, I think the solo thing probably is the closest thing to my heart.

For the tour that’s coming to Pittsburgh, what is a typical solo show like for you then?

Well, this time I’m going to say it’s the same as what I normally do. It’s the same in the sense that I’m standing up on the stage with a guitar and I sing songs and I tell the odd story. This time I think I’m just playing songs that I really feel close to for one reason or another, and it’s kind of a long set list and usually what happens is you start a tour and the set list usually just kind of presents itself, you start playing different songs, and it takes a shape without you even really consciously trying to do that and so probably by the end when I get to Pittsburgh, it’ll be working.

When you went solo, was there another artist that you could model what you wanted your career to be like, or was it all this new territory for you?

It was pretty new territory, really. When the old band broke up, which was a long, long time ago, really my old band was over at the end of ‘83. So it was very short lived in the original band format. We limped along for another couple of years and made another record, but it was really done by then. We just didn’t realize that at the time, but I’d been playing solo, guitar and singing songs, publicly since I was 14. So for 15 years, I guess, I’d been playing solo. So when the band broke up and I found myself on my own, it was familiar territory. I was quite happy to be on my own. I didn’t really mind at all. But then what I discovered was, I was gonna have to find an audience. That’s where the hard work came in really, in just going out on the road and finding an audience. That’s kind of what I’m still doing. In one sense, I was gonna say it’s been a hard slog. I mean, it hasn’t really been a hard slog. It’s been a lot of work, a lot of miles traveled. But there’s something addictive about it. There’s something addictive about that kind of battle. It’s quite spare, it’s quite a bare thing. It’s usually just me and a tour manager. We drive a lot of miles and we turn up in a town and we check in somewhere, and it’s all about those two hours at night. There’s something quite addictive about it. I don’t quite know what it is, but it has its own rewards.

You just released “Man @ Work Volume 2” earlier this year. So what sparked the sequel 22 years after the first one?

I think it was the record label that mentioned it to me, Compass Records. I think that was the first record that I made with them. When I first started working with them, they said, well, look, no one really knows who you are, your name anyway. People know what Men At Work is, but they don’t already know your name. So would you consider doing a record called “Man @ Work”? And obviously, it had come to mind before. I think I’ve had a couple of tours that were called Man At Work as well. So it’s quite an obvious way to go, so that’s what we did. It’s still probably the most successful solo record that I’ve done. So they suggested doing a sequel to that, or another volume. Plus the fact I don’t really think that I had another album of material. I released two albums during the pandemic, one called “Now and the Evermore” and then a covers record. I liked the idea of mining the rest of the Men At Work material and seeing what I could do with that. I think I’m pretty much done with that now. There’s not really that many more songs to reimagine, if you like. Then the rest of the songs, I just recorded songs that I really liked myself, so I re-recorded them. I think there’s a couple of things that I kept, maybe the strings on one song. But I re-recorded all the vocals and guitars and things so they’re basically new versions of those songs. They’re just songs that I like myself.

Related

• Q&A: Wolfgang Van Halen on Mammoth's new album 'The End'• Q&A: 'American Idol' winner Abi Carter bringing No Amount of Dark tour to Pittsburgh

• 2025 Pittsburgh area concert calendar

Whenever you do that, do you feel like it breathes a little bit of new life into those older songs?

Yeah, because there’s always things about songs that you think, well, yeah, I could do that a little bit better. Or you might even just get a different microphone that you like to sing into that you think, oh, this sounds cool, and you record it and it has a different flavor to it. Or you’re working with different musicians, and they bring something else to it as well.

How hard is it to change or modify a song that you’ve been playing for 30 or 40 years? Is it hard once you start playing to get out to get rid of the muscle memory?

A little bit. I usually don’t really think about that too much. I think that songs just usually change a little bit on their own without you consciously trying to. And especially, I’ve been working with the same musicians now for seven or eight years, and there’s something great about that as well, just in the sense that there’s a comfort level and you start to play. It’s difficult to explain, but I think you’ll probably understand. It’s like when you work with a certain set of musicians, after a little while, something else takes over where everyone starts to play with one another, but it’s not really consciously trying to do that. There’s the shifts and it’s got breath in it, and it’s got life in it, and a certain set of musicians, it kind of develops its own life after a little while, but you can’t force that and you can’t make that happen. It just either happens over time or it doesn’t. So I think that that’s what I have now with this particular set of musicians. It’s like that.

Are you thinking that there’s going to be a third volume of “Man @ Work” somewhere down the line?

No, I’m not thinking about that. No, I think I’ve pretty much mined all the Men at Work stuff. I think there’s life in the Men @ Work moniker, just because of the fact that Men at Work is still a more powerful brand, if you like, if you want to get into that whole thing of branding, which I don’t feel particularly sophisticated about. But people still probably know that name more than they know my name. So if you call something “Man @ Work,” whether it’s a band or a record or even just whatever it is, it tells the story, OK, well, it’s that guy from Men at Work and he’s on his own. It’s a solitary thing. So it’s kind of self-explanatory. So I think there’s life in that name, in some way, shape or form, but I don’t know whether I’ll make another record called that. Who knows? I’ve got no idea at this point. This one just came out, so I’m not thinking about another one at this point.

Twenty years down the road, you’ll be good for No. 3.

Yeah, if I’m still walking around. (laughs)

Speaking of Men at Work, what do you think the legacy of that band is? Do you think that it had more to give? Was there more there if you had stuck together?

Oh, yeah, I think there was definitely more there. I think we could have done a couple of other things, or who knows? The particular dynamics of the band, if you like, I think the problem with a lot of bands, certainly the problem with our band, was that there was a distinct lack of being able to communicate properly. I think that when you have five or six men together, there’s an inherent difficulty in the communication skills of men. So what happens is that whatever problems you have tend to fester. Our manager was my friend. He didn’t have great skills in trying to keep the thing together. He was more concerned about me, and he really cared about me more than he cared about anyone else. So you didn’t have a facilitating force that was going to keep the whole thing together. So it all kind of imploded and fell apart. The rhythm section got sacked was what happened first, at the beginning of ‘84. And that left three of us, Greg (Ham) and Ron (Strykert) and I and Russell (Depeller), the manager. But we were done. We were done. The band was really the five musicians and Russell, the manager, that was what the band was. And that’s how we conquered the world. That should have been what stood, and that should have been what kept going forward, but it wasn’t to be.

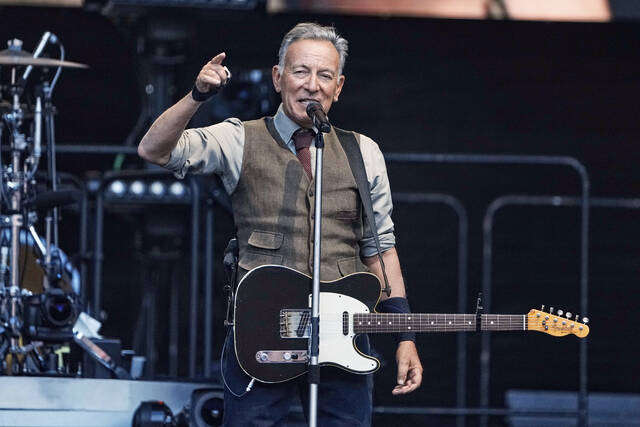

Touring with Ringo Starr, how long did that take to be “normal” for you to be like, oh, that’s Ringo?

Oh, it’ll never be normal. (laughs) It’s Ringo. He was in the Beatles. Come on, it’s never going to be normal.

So could you ever imagine writing a song for him, with “What’s My Name?”

Well, it just seemed at the time when I wrote that song, I checked to see whether there already was one, because he used to say it every night, and indeed still says it every night, and I thought surely there’s going to be a song called “What’s My Name?” and there wasn’t. So I just wrote one, and he liked it, and so he recorded it.