https://triblive.com/business/lawsuit-claims-nippon-failed-to-avert-fatal-clairton-coke-works-blast/

Lawsuit claims Nippon failed to avert fatal Clairton Coke Works blast

A lawsuit filed by the sister of a man killed in an explosion at Clairton Coke Works last summer alleges that if owner Nippon Steel had addressed ongoing, known safety concerns at the facility when it took over U.S. Steel, her brother would still be alive.

Trisha Lynn Quinn, the administrator of Timothy Quinn’s estate, sued Nippon and two other companies on Thursday in Allegheny County Common Pleas Court, alleging negligence and wrongful death.

The defendants are Nippon Steel North America Inc., which took over U.S. Steel in June in a $14.9 billion deal; MPW Industrial Services Inc., of Hebron, Ohio, which had been hired to clean a gas isolation valve that morning; and Valves Inc., of Pittsburgh, which had refurbished the valve in question 13 years earlier.

U.S. Steel and MPW Industrial Services did not immediately offer comment on the lawsuit.

Valves Inc. declined to comment.

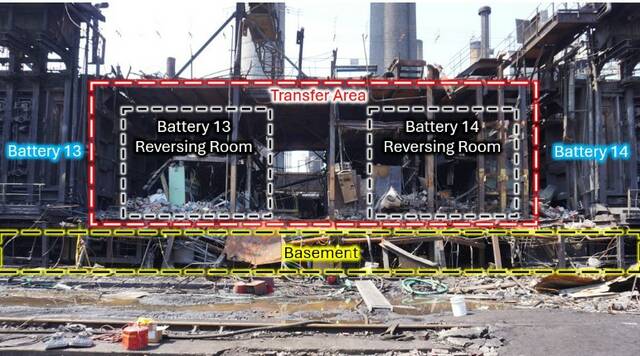

Timothy Quinn, 39, South Huntingdon and Steven Menefee, 52, of East Huntingdon, were killed in the Aug. 11 explosion at the 13-14 Coke Battery transfer area.

Eleven others were injured.

Quinn, a father of three, worked as an operator in the Battery 14 reversing room — a control room for the coking process — and on the morning of the blast was at his workstation 10 to 20 feet above the failed valve and explosion epicenter, according to the lawsuit.

A coke battery, a large industrial structure, houses multiple slot-shaped ovens used to heat coal to 2,000 degrees to create coke for use in steelmaking. It generates flammable, toxic gas.

Following the disaster at the Clairton works, the biggest coke facility, in the Western Hemisphere, two independent investigations determined the explosion was caused by the rupture of an 18-inch cast-iron valve which released coke oven gas into the area and then ignited.

That valve, according to the lawsuit, should have never been in a position to fail the way it did — one of a series of missteps Quinn claims led to the explosion.

The lawsuit also alleges Nippon did not ensure safety standards were followed when it took over U.S. Steel; MPW used improper methods to clean the leaking valve; and Valves Inc. failed to recommend the old cast-iron valve be replaced by more flexible steel.

Last week, following its own investigation, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration fined U.S. Steel $118,000 for 10 violations stemming from the Clairton Coke Works explosion.

Of those, nine were for inadequate safety procedures, employee training and equipment to isolate machines from energy sources. The final violation asserted that U.S. Steel failed to supply the agency with incident reports in a timely manner.

OSHA also cited MPW for nine violations stemming from procedural and training issues, totaling $61,000 in fines.

According to independent probes by the U.S. Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board and Engineering Design and Testing Corp., which was retained by U.S. Steel — the explosion occurred in the “transfer area” between Batteries 13 and 14, which housed control rooms, a break room and personnel shacks.

It was beneath that transfer area, in a confined space called the “basement,” that the high-pressure coke oven gas supply piping ran, feeding processed gas to both batteries.

The operational facilities were just 10 to 20 feet above the “basement” and were not constructed to be blast-resistant, a violation of industry guidelines, the lawsuit said.

‘Catastrophic hazard’

According to the lawsuit, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration requires facility siting evaluations for plants like Clairton Coke Works. The complaint alleges, however, that in evaluations conducted in 1998, 2003 and 2008 — facility siting was not addressed.

In 2003, the lawsuit said, the team conducting the OSHA analysis sent written recommendations to U.S. Steel urging the company to conduct a study of the coke batteries “to evaluate whether occupied buildings were appropriately located relative to explosion hazards.”

However, the lawsuit continued, management at the Clairton location rejected the recommendation, writing that the coke oven gas system was not explicitly covered by OSHA’s regulation.

However, OSHA updated its guidance in 2013, the complaint said, making the requirement clear.

Still, the lawsuit said, U.S. Steel continued to maintain that it was not required.

The layout of Battery 13/14 didn’t change, according to the lawsuit. Employees continued to be stationed in the break room and reversing rooms right above the high-pressure coke oven gas piping “completely unaware they were positioned atop a catastrophic explosion hazard that their employer had been repeatedly warned about and consistently refused to address,” according to the lawsuit.

Nippon Steel, through its due diligence prior to taking over U.S. Steel, should have been aware of the previous facility siting recommendations and U.S. Steel’s failure to complete them, the lawsuit claimed.

Therefore, the lawsuit continued, Nippon should have known the occupied buildings housing workers were improperly sited close to “‘a blast zone’ — the area subject to catastrophic overpressure and structural destruction in the event of a vapor cloud explosion.”

When Nippon took over, the lawsuit said, the company had “absolute authority and operational control to order immediate corrective action.”

Quinn’s lawsuit maintained that could have included completing the facility siting evaluations; temporarily shutting down battery operations until the occupied buildings could be relocated or safely retrofitted; or relocating workers to a safer location.

“Nippon Steel made a conscious corporate decision not to exercise its authority to implement safety corrections,” the lawsuit said.

By failing to take action, the complaint continued, Nippon Steel “adopted U.S. Steel’s prior negligence as its own and assumed direct responsibility for the consequences.”

Other factors alleged

The lawsuit also alleges that Valves Inc., which, in 2013, refurbished the 18-inch cast iron valve that failed, should have known that it needed to be replaced.

The complaint said cast iron is inherently brittle, with limited ability to flex, and that Valves Inc. should have recommended replacement with a modern steel valve instead of refurbishing the original.

At the time of the explosion, the valve was 72 years old.

The lawsuit also places blame for the explosion on MPW Industrial Services, which had been hired to flush residue from the Battery 13 gas isolation valve seat after a coke oven gas leak was discovered on July 8.

Although an outage was scheduled for August 19, MPW decided to “exercise” the gas isolation valve the morning of Aug. 11, the complaint said.

Three employees arrived about 10:30 a.m. However, the lawsuit alleges that they did not participate in a hazard analysis meeting on July 28, nor did they have a comprehensive briefing on the dangers of the coke oven gas system.

According to the complaint, Clairton Coke Work’s written procedures for exercising battery gas isolation valves allows for heating it with steam.

MPW is alleged to have used pressurized water instead — a move the lawsuit called a “fundamentally dangerous principle.” Without an outlet for the water, “the pressure rises instantly and theoretically infinitely until the weakest component in the system ruptures.”

When the MPW employees began pumping the water into the valve, the lawsuit said, one of the valve’s flanges began to leak, indicating the pressure was too high.

But, the lawsuit said, MPW did not stop injecting water into the system.

“By failing to recognize that their specific pump type would act as a hydraulic ram against the closed valve and stopping it when the valve began to fail, MPW turned a routine maintenance task into a mechanical demolition of a critical safety infrastructure,” the lawsuit said.

“Because water cannot be compressed to accommodate the incoming volume, the internal pressure within the valve body spiked violently and immediately.”

Employees soon heard a “pop,” and pressurized coke oven gas rushed out of the failed valve, “rapidly filling the confined basement space and rising toward the occupied buildings 10 to 20 feet above” where Quinn was working.

The workers’ gas detection monitors began sounding, and nearby workers were directed to evacuate.

Less than a minute later, the gas ignited and the coke battery exploded.

“Walls collapsed, the roof was lifted and blown away, and structural elements disintegrated under the explosive overpressure,” the lawsuit said.

“Timothy Quinn was struck by the pressure wave, impacted by collapsing structural elements, bombarded by flying debris, and subjected to the full force of an industrial explosion at close range, and died as a result.”

TribLive staff writer Jack Troy contributed to this report.

Copyright ©2026— Trib Total Media, LLC (TribLIVE.com)