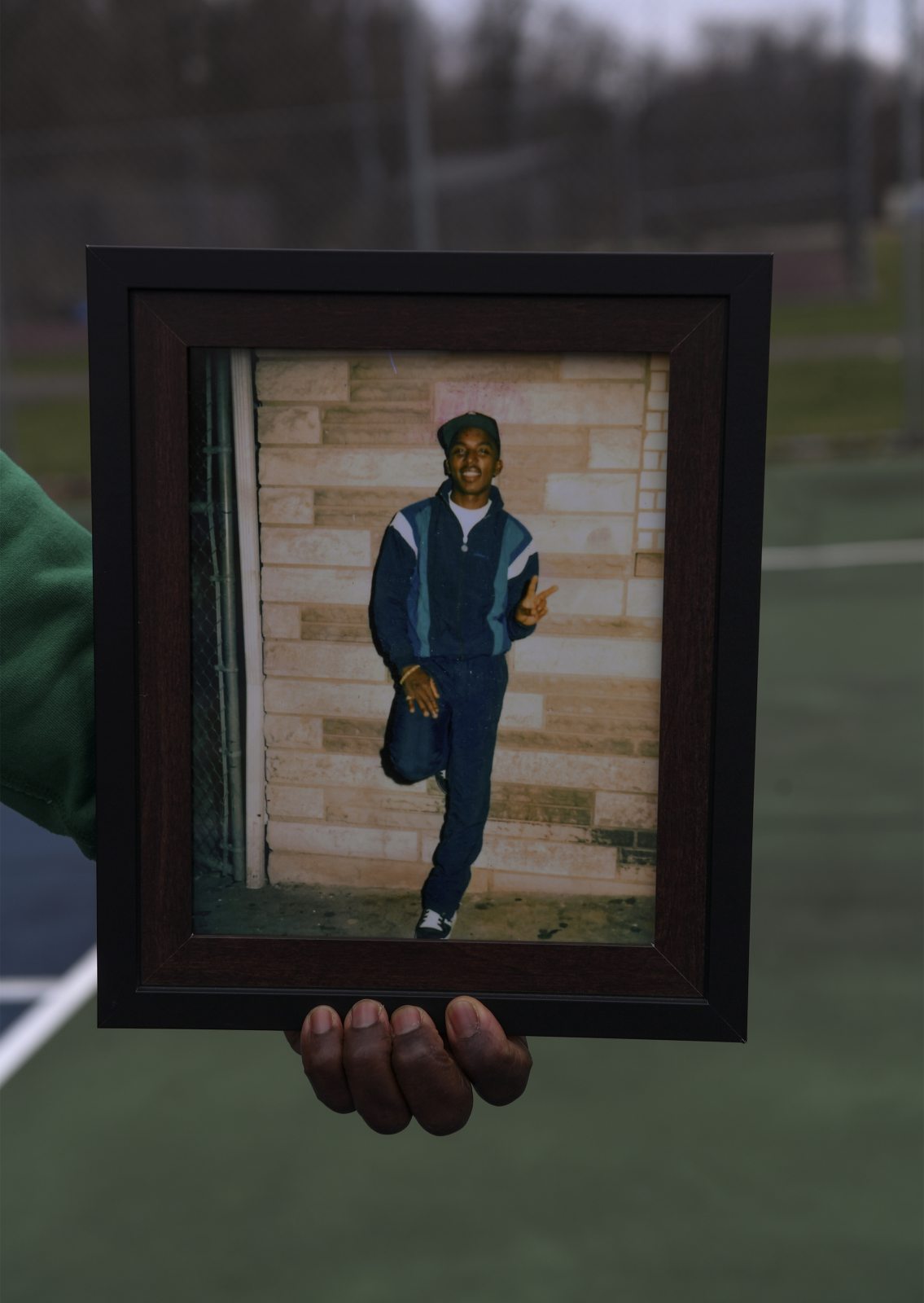

Wesley Smith Sr, 48 of Swissvale, holds two photographs of his brother Deondre “Boukie” Smith at Kennard Field Park in the Hill District section of Pittsburgh on Wednesday, Jan. 6, 2020.

Wesley Smith Sr, 48 of Swissvale, holds two photographs of his brother Deondre “Boukie” Smith at Kennard Field Park in the Hill District section of Pittsburgh on Wednesday, Jan. 6, 2020.

Feb. 6, 2020

Story by JoAnne Harrop | Photos by Louis B. Ruediger

A sibling is often someone’s first friend. The person who best understands the family’s dynamic. Someone who travels through life’s stages, shares memories of childhood.

Many forge lifetime bonds.

The death of a sibling can leave a cavernous hole.

“A sibling’s death becomes an anchor marker,” said Paul Friday, chief of psychology for UPMC Shadyside and president of Shadyside Psychological Services. “The sibling’s life freezes in that time. We try to move forward, but our sibling isn’t moving forward with us.”

The Tribune-Review interviewed five people who lost siblings, from as recently as September to as far back as 1979. They shared stories of heartache, loneliness and the challenges of living without their beloved brother or sister.

Unaddressed childhood grief and trauma can lead to short- and long-term difficulties, including decreased academic performance, mental health issues and early mortality, according to the New York Life Foundation.

In the United States, 5% to 8% of children with siblings experience such a loss, according to a study in the medical journal JAMA Pediatrics.

Sibling rivalries in younger years get resolved in later years and tight, lifelong bonds evolve, said Friday. The “tighter these bonds, the greater the grief when one sibling dies,” Friday said.

The age and cause of death — whether accidental or because of an illness — play a role in how someone navigates grief, Friday said.

“The older one is when the death experience occurs, the more established the next phase of one’s life is,” Friday said.

With the basketball hoops and backboard tattered and broken at Kennard Field Park, memories are vivid as Wesley Smith Sr. recalls games played with his older brother Deondre “Boukie” Smith who died Dec. 4, 2007.

Kennard Field is where the memories come into sharper focus for Wesley Smith Sr.

The stands are full. Everyone is cheering.

Smith’s brother Deondre “Boukie” Smith takes the court. Boukie was one of the best basketball players with his moves during this summer tournament in the Hill District. This playground is where Boukie felt most comfortable, said his younger brother Wesley Smith Sr.

“I can still see him,” Smith Sr. said as he stood at midcourt on a chilly January afternoon. “My brother was larger than life on this court. I remember (former Pitt basketball player) Eric Mobley set a pick on my brother during a game. I jumped over the fence and headed toward (Mobley) and hit him. He was a big dude, but my instinct kicked in to look out for my brother.”

Wesley Smith Sr, 48 of Swissvale, holds a photograph of his brother Deondre “Boukie” Smith Wednesday, Jan 6, 2020.

Boukie was usually the one who protected his younger sibling.

Boukie died of congestive heart failure on Dec. 4, 2007, two years after his medical issues were discovered. He was 41.

“My brother was everything to me,” said Smith Sr., 48, a carpenter with the Allegheny County Housing Authority. “When I come to this park, I see him so vividly.”

Smith Sr., a native of the Hill District who lives in Swissvale, said the memories at the park are happy ones.

He still remembers the call from his brother’s girlfriend — the call that changed his life.

“It was 6:17 a.m.,” said Smith Sr., who has older sisters Carmen Smith and Kelli Smith. “My brother was pronounced dead a few minutes earlier at 6:14 a.m. When you lose a sibling, there is no more normal. Life is never, ever, ever, ever, ever going to be normal again. And no one understands that unless it’s happened to them. He was my big brother. I looked up to him. He was my protector, sometimes too overly protective of me. My dad wasn’t around, and my stepfather was a drug addict. So my brother was the man of the house: my brother, my father and my friend. People tell me I sound like my brother.”

He likes when he hears that.

His brother was a sharp dresser. Everything had to match. If he wore an Adidas shirt and shorts, the shoes were also Adidas.

It is important for Smith Sr. to talk about the loss.

When Boukie died, the family learned he had no life insurance.

Smith Sr. put his brother’s photo on jars and took them to bars and barbershops that he frequented to collect money. The donations were many.

“He was admired by a lot of people,” Smith Sr. said. “I love to talk about him every day. I love to reflect on his life. I don’t want people to forget. He got taken away from us. I feel him here … on this basketball court … driving to the hoop to take a shot … the crowd going wild.”

Christian McDowell, 16, lost his sister Caileigh four years ago to undiagnosed Crohn’s disease. Christian’s grieving continues for his only sibling.

Caileigh McDowell’s dad bought her a teddy bear.

“Teddy” went everywhere with the little girl, including her final days in the hospital.

On April 2, 2016, at age 17, McDowell died of complications from undiagnosed Crohn’s disease.

On the day of her funeral, her younger brother, then 11-year-old Christian, gave “Teddy” one last hug. He took its photo, then placed the stuffed animal in the casket.

The gestures brought tears to his mother’s eyes. He continues to amaze, Lori McDowell said, despite the toughest loss of his life, his big sister.

Christian, 16, has a locket with a photo of him and his sister.

Christian McDowell holds a locket with a photo of him and his sister Caileigh who died in 2016 from undiagnosed Crohn’s disease. Christian was 11 at the time of her death.

“It is hard for someone to understand the pain and the loneliness of losing your only sibling unless you have gone through it,” said Christian, of Oakmont.

To honor his sister, he dressed in a white suit to accept her high school diploma at Woodland Hills High School. She would have worn a white dress that day.

Christian plans to use his sister’s backpack for his senior year. It sits in her bedroom, untouched like so many of her belongings. Christian entered her room many times in the fall to turn on the lights on Fridays during high school football season. Caileigh loved the feel of “Friday night lights,” he said.

Christian, who plays football, wears No. 56 — because 5 + 6 = 11. Caileigh’s birthday is April 11.

Portraits hang in the living room at the McDowell home on Dec 1, 2020. Christian McDowell, 16, lost his sister Caileigh four years ago to undiagnosed Crohn’s disease, Caileigh was 17 when she died.

“Hold your loved ones close because every day is not promised,” he said. “Little fights aren’t worth it.”

The first Christmas without his sister, the family went to a hotel. Staying home would have been difficult. Christmas is never the same. No holiday is ever like it was.

“If you know somebody who has lost a sibling, they need your support,” he said. “I think of all the things she will miss. She won’t be here for my first prom or when I go to college or when I get married and have kids. I will never be an uncle.”

Siblings are supposed to make it all the way to the end with each other, said his aunt Lynn Banaszak.

Christian recalled holding his sister’s hand as she lay on the bathroom floor, fighting for her life, before the paramedics arrived to take her to the hospital one last time.

A cherub angel and dried flowers are placed near a photograph of Caileigh McDowell who died of undiagnosed Crohn’s disease in 2016.

Isolation in the house during the pandemic makes the grief much more difficult, Christian said. He feels a close bond to his cousin Colin McDowell, who is like a sibling.

“I admire Christian,” Banaszak said.

Banaszak said a therapist told the family that the death of a child affects the entire family. It’s like they were all on a ski trip and everyone breaks their legs and arms. They have no way to help each other because they are all in pain.

The family created The Caileigh Lynn McDowell Foundation, which facilitates a monthly bereavement meeting where families can support one another. Lori McDowell said it’s a way to carry on her daughter’s memory.

“It is hard to push through each day,” he said. “Not the kind of hard to push through another rep in the weight room. It’s hard to explain. You have to fight every day. It’s like a 16-round fight every day.”

He talked about honoring his sister’s memory and why he placed “Teddy” in the casket.

“She needed ‘Teddy,’ ” Christian said. “He went with her. It would have been selfish of me to keep ‘Teddy.’ ”

Lorri Lankiewicz pictured Friday. Dec 11, 2020 at St. Stanislaus Cemetery. Lankiewicz lost two siblings, a brother Ricky in 2012 and a sister Darlene in 1979.

At age 11, Lorri Lankiewicz delivered newspapers to an assisted living facility in Bloomfield. On the morning of April 17, 1979, when she returned home, her older sister Darlene would have already left for school.

“I was like, ‘Why are you still here?’ ” said Lankiewicz, now 53, a physical therapist and owner of Dr. Lorri’s Health Store and Fyzical Therapy & Balance Centers in Butler. “She told me she was running late. She left and came right back. She said she felt bad for not saying goodbye, and she kissed my whole face, which I pretended I didn’t like, but I really did.”

That was the last time Darlene Lankiewicz would kiss her little sister’s face.

A sophomore at Sacred Heart High School in Shadyside, Darlene took a bus after school to volunteer at Central Medical Pavilion in Downtown Pittsburgh. As she crossed in front of the bus, she was struck by a car.

She died two days later. She was 15.

A photograph of Darlene Lankiewicz rests on a granite bench at St. Stanislaus Cemetery. Darlene died in 1979, when she was 15 years old.

When Lorri received the call about the accident, the person driving her to the hospital, Nancy, told her she had to be strong for her mother.

“I was with her constantly when I was little,” Lorri said. “I idolized my big sister. And one day she walks out the door and never comes home.”

Lorri said her life has been inspired by an autobiography her sister wrote for a high school project.

“My sister Lorri, who is 11, always reminds me of concern and love. She feels that we should be working on new beginnings instead of reaching endings,” Darlene wrote.

In 2012, Lorri once again experienced the death of a sibling. This time it was her brother Ricky, who died of a heart attack at 52. She found support from her older brother Jeff and her wife, Melissa McCue, who make the emotional days — and there are many — more comforting.

Her cousin Renee recently sent her a card.

“I think of you often and my heart hurts for you. … You have experienced so much loss in your young life,” she wrote.

Lorri said her sister’s death initially felt like part of her had been ripped away.

“Over time, you don’t feel so ripped apart,” she said as she stood near her sister’s grave at St. Stanislaus and St. Anthony Cemetery in the Etna/Millvale area. “You start to feel like part of you is being stitched back together again. But the loss is always there. It resides in the depth of your cells.”

It begins with the first birthday, the first Christmas, the first year after she died. The grief grows.

“You think, ‘Oh my God, it’s been 40 years,’ ” said Lorri, who also lost her father Richard and most recently her mother, Antoinette “Toni” Lankiewicz, in 2019. “Grief has been a companion of mine since I was young. I keep it close but do not let it rule my emotions.”

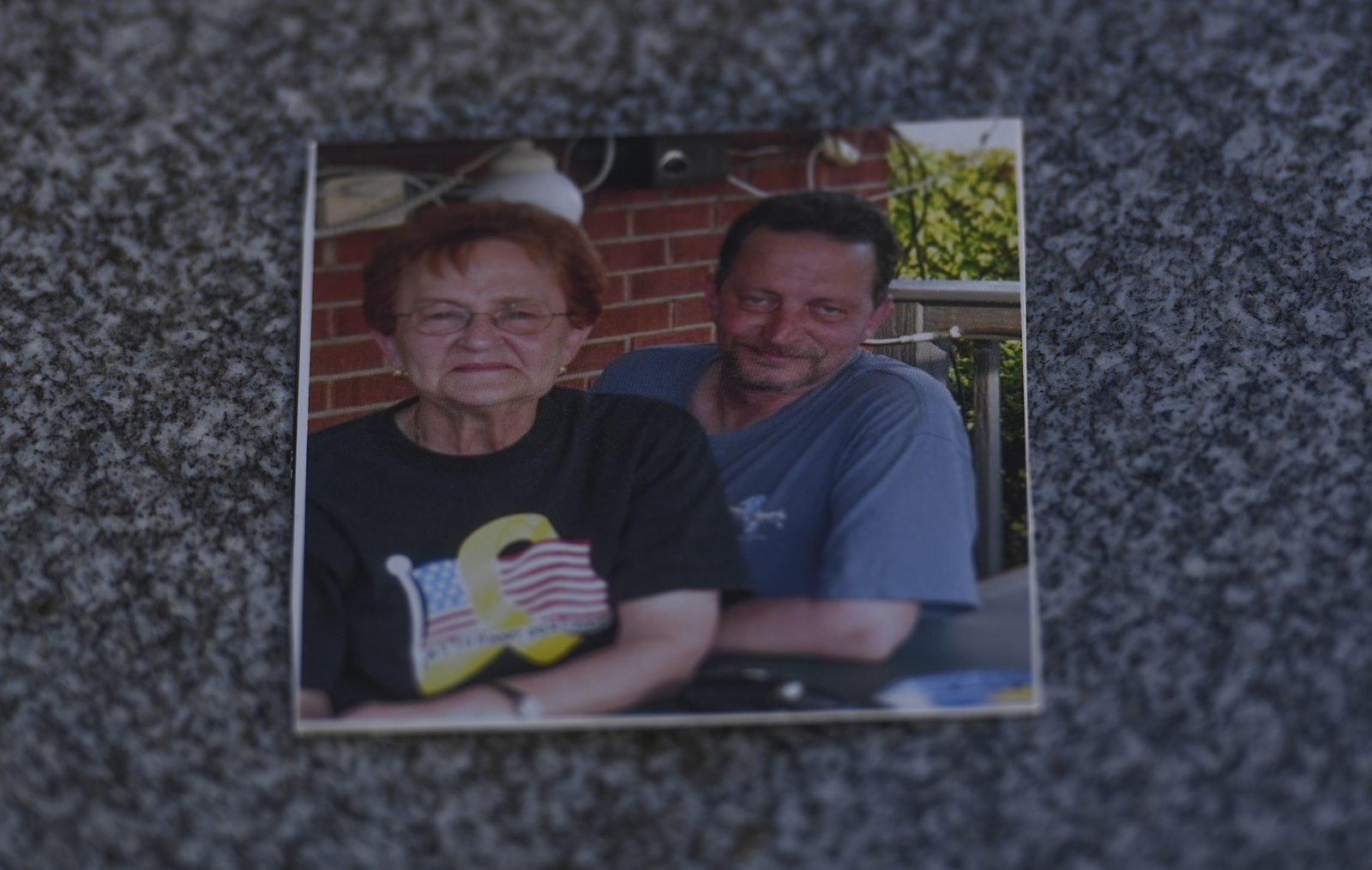

A photograph of Lorri Lankiewicz’s mother Antoinette “Toni” Lankiewicz and her brother Ricky Lankiewicz rest on a granite bench at St. Stanislaus Cemetery.

Seeing Darlene in the intensive care unit, a ventilator breathing for her, connected to tubes and machines, is a picture forever in Lorri’s mind. Darlene was an organ donor.

“The one person I wanted to talk to wasn’t there anymore,” she said. “There are so many things that happened to me in my life that I wanted my sister to be there with me.”

She often recalls their final day.

“I wonder, why did Darlene come back in to say goodbye to me that day?” Lorri said. “Did she sense something might happen? I will never know the answers to those questions until I see her again.”

Natalie Shiffler, 26, of Hempfield holds a photograph of her brother Judson, 18, who died in a car accident on Dec. 30, 2014.

A knock on the door woke Natalie Shiffler.

“When I opened it, there was a policeman who said, ‘There has been an accident involving a car registered to this house,’ ” said Shiffler, 26. “I was half asleep and didn’t know if my mom or dad or brother was driving the car. It’s all kind of a blur.”

Her brother Judson had been flown by medical helicopter to UPMC Presbyterian in Oakland.

The date was Dec. 29, 2014.

He died the next day. Judson was 18. He was an organ donor. Natalie’s parents Meg and Bill Shiffler shared the story of their son helping to save others’ lives in a March 2015 Tribune-Review story.

“It’s such a traumatic experience, you don’t know how to handle it, so you repress some things and you think, ‘that should have been me,’ ” she said. “I was his older sister. I was supposed to be his protector.”

Shiffler said it was difficult going back to Penn State University after the funeral. She was a member of the track and field team. It’s important to check on the mental health of someone after a life-changing event, she said. She wants to break the stigma around mental health, especially in athletes.

“I experienced that firsthand,” she said. “I went back to school the third week in January and competed in a meet. I was in shock. My coaches didn’t sit me down and tell me if I needed time to take it. I lost my love for the sport. It wasn’t fun anymore.”

She said mental health checks should be done like regular yearly physicals.

“Your body can be fine, but you need your mind in the right space,” she said.

Shiffler recalled that, a year later, her Aunt Kim asked whether she was OK.

“You sometimes feel like you are walking on eggshells because some people don’t want to talk about it,” Shiffler said. “There were times I didn’t feel like I was seen.”

Two days before the accident, she and Judson went to Forbes State Forest with their cousin Adison and their nan, Sally.

“It was our last adventure together,” she said. “It’s marked on my right side forever.”

She had the coordinates tattooed on her right ribs.

A photograph of Judson Shiffler after he became the WPIAL 50-yard freestyle champion in 2014, on display in his families home on Feb. 16, 2015. (Tribune-Review file)

“I tell my friends if they are fighting with their siblings to call them,” she said. “I would give anything to get a call from my brother. It was just me and my brother. Sometimes it feels like forever, and other times it feels like yesterday. I struggle with my emotions. It wasn’t like he was sick and we knew what was coming. It was like ‘Boom,’ and he was gone. You think he is going to walk through the door.”

There is a cross at the crash site at Route 136 and Millersdale Road, down the road from Hempfield High School. Judson was an elite swimmer and earned a college scholarship.

“It was very hard not being able to watch him compete at the collegiate level because I know he would have dominated,” she said. “He would have also been a great student and teammate.”

She said she has friends who have been like a brother, but it’s not the same. She wishes she had more videos of her brother so she could hear his voice.

Shiffler tells her friends to not fight with their siblings because you never know the news you might wake up to.

“When I arrived at the hospital, Jud looked fine,” she said. “I won’t know what really happened until I see him in heaven.”

Angie Van Every, 29, of Cheswick holds a photograph of her brother Warren Van Every, 31, who died of a heart attack on Sept. 25, 2020.

As Angie Van Every was planning for her wedding, there was one person even more excited than her and her groom.

“My brother was so looking forward to our wedding,” said Van Every, 29, of Cheswick. “He was so excited.”

On Sept. 25, the day she was picking up her gown, she received several text messages asking about her whereabouts.

“When I got home I was so excited to talk about my dress, and my parents told me my brother died,” she said. “It wasn’t supposed to happen this way. To know he wasn’t going to be at my wedding hurt so bad. This is horrible to say, but I am glad he left me first because I would not wish this on him. It is the hardest thing ever.”

Warren Van Every died of a heart attack at 31 — three weeks before his sister’s wedding. The Aspinwall volunteer firefighter “was one of the kindest people you would ever want to meet,” his sister said. “He was so devoted to the fire department. He was a friend to everyone.”

To honor him at her wedding on Oct. 16, she placed a picture of him on the chair where he would have sat, along with a corsage and candle.

Angie Van Every and husband Patrick Saunders pose for a photo on their wedding day. In between them is a photo of her brother Warren Van Every, who died a month earlier. (Courtesy of Ashley Sara Photography)

“We served him dinner,” his sister said. “And we had a pie table, so I made sure he got a piece of pie, Oreo cream. It was an extremely difficult moment but also a tender moment.”

The next day, she and her husband dressed in their wedding attire and went to her brother’s grave.

“I danced on his grave, holding his picture,” she said. “It was a moment I will never forget.”

Losing a sibling at a young age is something you never think is going to happen to you, she said.

“It feels like I am in a movie sometimes,” she said. “It doesn’t seem real. When we have a baby, he would have been the best uncle. The holidays are extra sad without him.”

She said her heart broke the day her brother died. She thinks about him every single day, she said.

“I am so proud of him and all that he did for his family, friends and community,” she said. “I hear that the pain in my heart will soften with time — and I look forward to that day.”

Van Every said what was most frustrating on her wedding day is people would tell her, “He is with you in spirit.”

“I didn’t want to hear that,” she said. “I wanted him to be here. I still want him to be here. It’s been an emotional 2020. This was supposed to be the year I got married and started a wonderful life with my husband Patrick, not the year I lost my brother. Patrick loved my brother like his own brother. On our anniversary, I will think about my brother and how much he wanted to be at our wedding. It’s just not fair that he wasn’t.”

Never use the phrases “You should,” You have to,” “You must not,” or You better not,” or give advice on what you would do if you lost a sibling, said Paul Friday, chief of psychology at UPMC Shadyside.

The most helpful thing that someone can do is listen.

“There is a far, far more consoling aspect to listening intently with compassion than with telling someone what they can do to feel better,” he said.

If appropriate, touch and hug. Sit if the person is sitting or stand if he or she is standing.

“Sibling loss, like any significant loss, just like gravity: it sucks,” he said. “Time helps, but the pain is palpable in the loss of part of you that can never be recaptured.”

JoAnne Klimovich Harrop is a Tribune-Review staff writer. You can contact JoAnne at 724-853-5062, jharrop@tribweb.com or via Twitter @joannescoop.