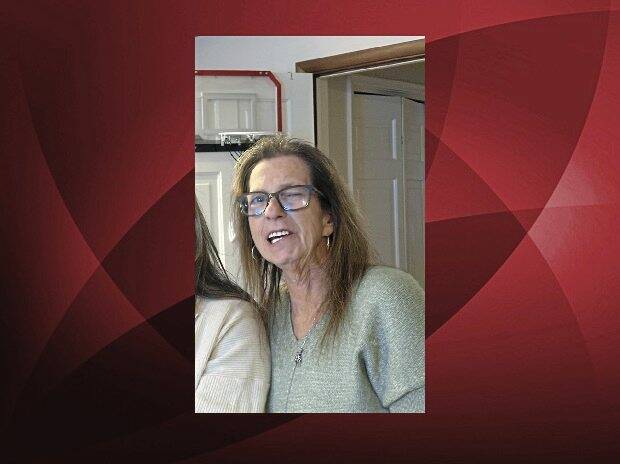

Dannielle Brown and Duquesne University President Ken Gormley appear to want, in principle, the same resolution to Brown’s two-month hunger strike: to keep students safe and to find closure surrounding the 2018 death of Marquis Jaylen Brown.

In practice, the two — one a grieving mother and the other an educator overseeing 6,000 students — both feel they must seek that resolution from different directions.

Brown began her hunger strike on the Hill District’s Freedom Corner on July 4, and she splits her days between that corner and Duquesne’s campus. She recently secured an apartment — she’d been sleeping in a tent for months — to retreat to as the nights get colder. She has said she is taking vitamins and drinking fluids, but she is not eating.

Her son, known to most as JB, was celebrating his 21st birthday Oct. 4, 2018, when something — some suspect synthetic marijuana — caused him to act erratically and ultimately jump through his dorm room window on the 16th floor of Brottier Hall.

“I would like to see Dannielle find peace and closure,” Duquesne University President Ken Gormley told the Tribune-Review. “I really do care about her. I care about her mom and dad. I care about her other son, Jamal — the whole family.”

He said there is no way to change what happened to JB, “but we can always be there for her. And I plan on always being there for her.”

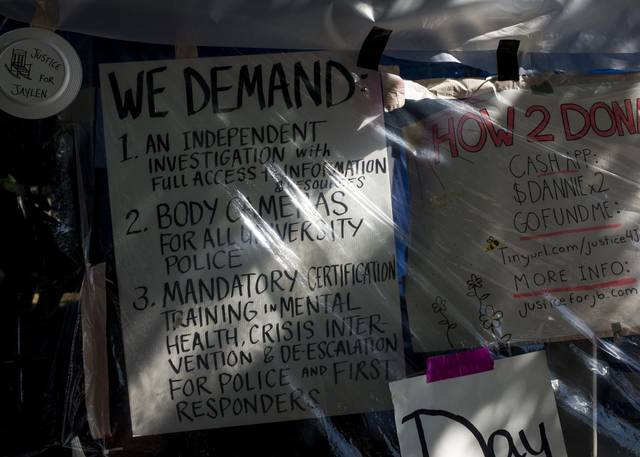

Brown has said she wants to conduct her own independent investigation, believing there is more to the story or, at the very least, Duquesne should have done more to protect her youngest son. She’s demanded the university equip officers with body-worn cameras, and she wants them to undergo better training for how to handle a student in crisis.

On Friday, she and hundreds of supporters marched through Pittsburgh, winding through a number of campuses to honor her son, honor the lives lost on Flight 93 on Sept. 11, 2001, and to call for more protections for students. She wants body cameras and training not just for Duquesne and not just for Pittsburgh-area campuses, but for all campuses nationwide.

“It should never be an officer’s narrative against you all,” she told the crowd. She said the chief of Chatham University police spoke with her before the demonstration started, and she was wearing a body camera. Brown said the chief told her the school had recently equipped their officers with them, in part because of Brown’s movement.

Gormley and attorneys for the school have said the confidentiality agreement is standard and required of the university by law. He said it is meant to protect the mental health of others involved.

“We can’t just sit here and start handing out private documents to people without following the procedures,” he said. “There were other people impacted by this tragedy too, including students who were present … who were deeply saddened and affected by that experience. I have to watch out for them, too.”

He said some are still working through what they experienced that night, and doing nothing to keep their names out of the public spotlight could lead to publicity that might retraumatize them.

Gormley said the process has become more muddied now that Brown’s early attorney, S. Lee Merritt, is no longer involved in the case. Because Brown has set the wheels in motion to sue the university, any conversations not had through attorneys halt the process for even longer.

“Once you are sued, you have to follow the rules that apply to litigation. This is no longer just an information discussion,” he said. “We can’t sit down and negotiate individually with her without a lawyer present.”

Brown in February 2019 filed a praecipe for a writ of summons — a document filled out by someone intending to sue another party that begins the legal process.

Stopped outside Carlow University shortly before 12:30 p.m. on Friday, Brown said she planned to have conversations with all university presidents regarding body cameras.

“I want to know what’s the plan,” she said.

Later, leading her supporters toward Duquesne, she told them to question the university’s narrative. She said she doesn’t have the school, though.

“There’s no hate in my heart,” she said. “I just want people to trust me enough to understand: I want to know what happened to my child.”

She said she’s adopted all of her supporters and college students everywhere in the absence of her son. She wants to keep them safe, she said.

Gormley said that is his goal, too. Right now, much of his focus is on protecting his students, staff and faculty from covid-19.

“Even as I devote all my waking moments to that, I’m always going to care about Dannielle regardless of what Dannielle does because I know there is no way to explain what is going through her mind and how she’s going to reach a point of closure,” he said. “I’m going to help her get there no matter what it takes.”

Brown, for her part, spoke directly to Gormley as she livestreamed her march from Oakland to Duquesne, during which she crossed the athletic field and stopped to speak at the bench dedicated in memory of her son.

“Hey Ken, I know you’re watching. We’re going to visit the bench — the bench the school so beautifully provided. Yet as beautiful as that bench is, I want the answers. I’ll trade the bench for the answers. I’d trade everything for the answers. And body cameras.”