It was the early 1890s and Scottish-American industrialist Andrew Carnegie was already one of the richest men in the world. Anxious to do something for what he called the “toilers,” the laborers and steel workers of Pittsburgh who enabled him to amass a fortune worth over $300 billion in today’s dollars, Carnegie decided to build a free library.

It was around this time that Carnegie broke the Steel Workers Union during the violent Homestead Strike in which seven workers were killed. Carnegie was sensitive to criticism surrounding his involvement in this. Some have speculated that it may have inspired the gesture, or at least accelerated the process of its completion.

Whatever the inspiration might have been, Carnegie, who had already built libraries in Braddock and Allegheny City (today’s North Side section of Pittsburgh), envisioned a far bigger operation in Oakland.

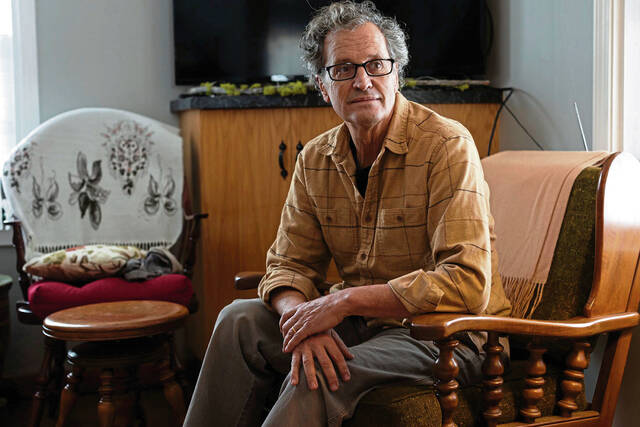

“This was his city and he really wanted to give back here,” said Mary Frances Cooper, president and director of the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh. “I think his vision of having something that was more than just a library was really important.”

On Nov. 5, 1895, Carnegie opened the Carnegie Institute, the building that today houses the Carnegie Museum, Carnegie Library and Carnegie Music Hall.

“He really wanted the people of Pittsburgh to experience architecture and art and dinosaurs and other items that they may not be able to travel around and see,” Cooper said. “I think he thought that bringing this together in a place where you could have music and art and science and literature all flourishing would be wonderful.”

Carnegie provided the seed money to build the library complex. The original structure cost just over $1 million, equal to $23.5 million today. Carnegie also donated all of the steel. His name can still be seen engraved on the beams.

However, he did not endow its operations. It was up to the community to furnish financial support.

“He was very explicit that this was a gift to Pittsburgh,” said Steven Knapp, president and CEO of the Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh. “It was inspired in part by his sense that he had not had the opportunity for a formal education, and he wanted to make the resources of the world, the arts and sciences and learning available to people who wouldn’t otherwise have the opportunity to experience them.”

The original building was modified a dozen years after it was built because Carnegie was said to have hated its design.

“He didn’t like the architectural effect of having this one long, narrow building with two towers at one end,” Knapp said. “He thought they looked like donkey’s ears. And so he decided to take down those towers and added a new wing that was perpendicular to the original one.”

“When you have a lot of money, if you don’t like it you can change it,” Cooper said.

One thing that remains from the original building are the 47 names of scientists, authors, artists and musicians inscribed along the top of the exterior of the building. Among them: Newton, Galileo, Shakespeare, Milton, Homer, Michelangelo, Brahms, Chopin, Tchaikovsky and Dvorak.

“It seems obsolete because, of course, our conception of art and culture extends way beyond the boundaries of Western European and American culture,” Knapp said. “But at that time, it very much reflected a 19th-century conception of art and science as these twin, but separate, disciplines.”

By placing the museums of art and natural history side by side, Knapp said, Carnegie “made it possible to explore the relation between art and science in a way that probably wasn’t so much what the 19th-century conception involved.”

Before the Carnegie Institute opened its doors in 1895, Pittsburgh did not have a symphony, let alone a place for one to play.

But that soon changed. Carnegie, who had served as president of the New York Symphony Society and had given Carnegie Hall to the City of New York, founded the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra.

“He was convinced that the Pittsburgh Orchestra ought to ‘take a permanent place among the great symphonic organizations of the country’ when few cities in America had one at that point,” said Melia Tourangeau, president and CEO of the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra.

The Pittsburgh Symphony’s first concert was Feb. 27, 1896, at Carnegie Music Hall in Oakland, where it performed regularly until 1910 before moving to the Syria Mosque elsewhere in Oakland, and later Heinz Hall Downtown. It’s now the fifth oldest major orchestra in the country.

“Carnegie was very proud of Pittsburgh and he wanted Pittsburgh to be a destination city like New York or the big European cities,” Tourangeau said. “So, if you wanted to have a city of that caliber, you had to have an orchestra, you had to have a museum, you had to have these cultural icons in your community.

“And the establishment of a symphony orchestra, at least in the late 19th century, was seen as proof to Americans and Europeans alike that it was a great city to come to and live and work.”

Carnegie built branch libraries all over Pittsburgh. He went on to build libraries in other parts of the country and other parts of the world. But it was the Carnegie Library in Oakland that became the significant jumping-off point for that work as well.

“ ’Free to the people.’ That’s what it says over our door, and we take that very seriously,” Cooper said. “It means that it is open for everyone. And it doesn’t matter who you are, where you come from or what you want or need, we will serve you.

“You’re welcome, and we will serve you.”