English teacher Anne Loudon knew of the late 1990s feud between playwright August Wilson and theater critic Robert Brustein through her knowledge of Wilson’s 1996 “The Ground on Which I Stand” speech that sparked the dispute.

What she didn’t know — but discovered during her summer research — were the “juicier” details, which she promptly incorporated into a new lesson plan for her Advanced Placement English Language and Composition students.

“I knew that there was this back and forth, but digging into the materials, it was so much juicier. I was like, ‘Ooh! The kids are gonna love this tea,’ ” Loudon said. “There was some bitterness and some bad blood under the surface.”

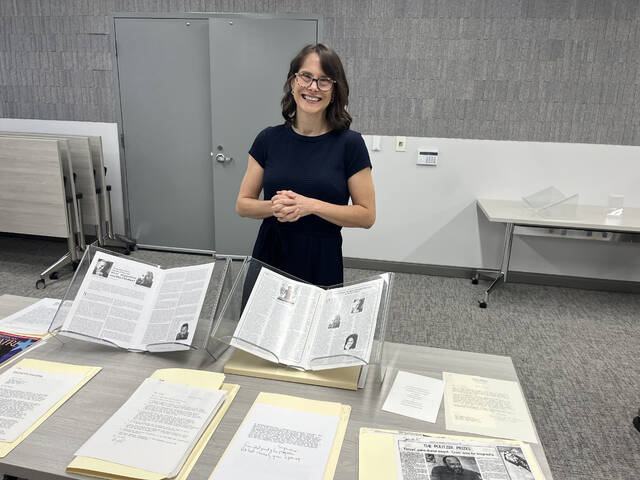

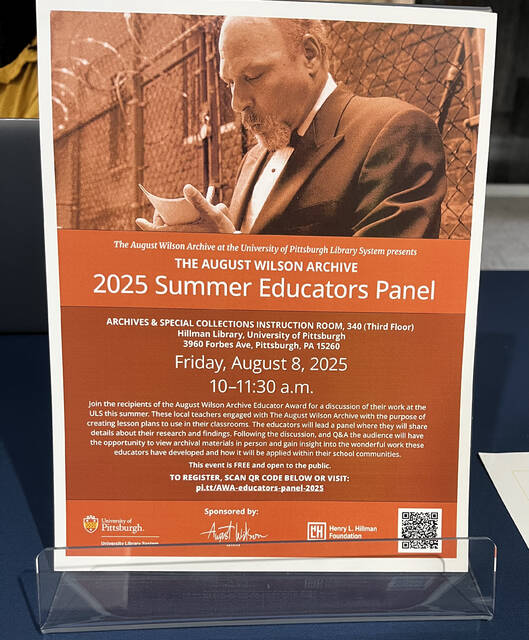

Loudon joined four other August Wilson Archive Educator Award recipients at the 2025 Summer Educators Panel on Aug. 8 at the University of Pittsburgh’s Hillman Library to present their new lesson plans.

The educator awards went to five local high school teachers, allowing them to come into the library over the summer and use the materials in the August Wilson Archive at Pitt’s University Library System for their research into creating new, Wilson-focused lesson plans for their classes this year.

Born in Pittsburgh’s Hill District in 1945, Wilson was a Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright best known for his 10-play series, “The Pittsburgh Cycle” (or “Century Cycle”), which chronicled Black American life in each decade of the 20th century. He died in 2005 at age 60.

Loudon already has taught one Wilson play, “Fences,” for years in her AP English Language and Composition course at Shaler Area High School. The course is designed to develop students’ understandings of rhetoric through reading, analyzing and writing about various texts. Though the texts are usually nonfiction, Loudon includes “Fences” in her curriculum to teach students how to examine rhetoric in fiction as well.

“Whenever I teach something like ‘Fences,’ I have to teach it through an argumentative lens,” Loudon said. “What is Wilson’s argument in this play? What is he saying about race? What is he saying about community?”

After 30 hours of research, she is ready to help students take what they learn during the “Fences” unit and expand on it with her new five-day lesson plan, titled “The Ground on Which He Stood: Wilson vs. Brustein as a Rhetorical Case Study.”

Loudon said she decided to focus on the speech and feud because “the AP Language course is a class that’s rooted in nonfiction argumentation and rhetoric.”

“So selecting a speech and all of the conversations that happened around the speech was just the perfect fit,” Loudon said during her presentation. “My students will already have read ‘Fences’ at this point, and they will have done research on August Wilson’s background, and they will understand who he was as a writer and what his motivations were. So that’s going to lead us into studying his speech.”

In his speech, which he originally delivered on June 26, 1996, at the 11th biennial Theatre Communications Group national conference, Wilson argued for the elevation of Black American art and critiqued the practice of “colorblind casting” — the casting of people of color into roles originally written for white actors — as “the same idea of assimilation that Black Americans have been rejecting for the past 380 years.”

He called out Brustein by name in the speech for insinuating that multiculturalism leads to “confused standards” in the theater world.

“Wilson’s stance was that, in order to truly achieve this diversity, you need to invest in Black theaters, you need to invest in Black artists so they can create authentic Black stories to give Black performers a true creative outlet,” Loudon said. “Brustein disagreed. He’s like, ‘No, you’re moving backward. You’re segregationist. You’re not being progressive-minded. Martin Luther King Jr. would disagree with you.’ And then it went back and forth, back and forth between the two.”

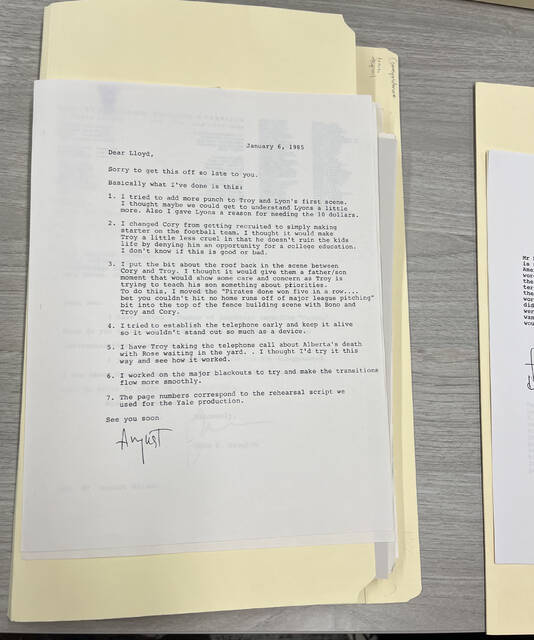

Loudon discovered the potential “bitterness” and “bad blood” behind the Wilson-Brustein feud in some of the news articles and correspondences included in the archive.

According to Loudon’s lesson plan, novelist and theater critic David Richards wrote in a 1996 article for The Washington Post that in 1979, Brustein was replaced as head of the Yale Repertory Theatre and dean of Yale’s school of drama by Lloyd Richards, a Black theater director and frequent collaborator with Wilson.

Loudon incorporates this information into the lesson plan so students can examine the context of the feud — a key step students must take to understand the broader “rhetorical situation” surrounding the original speech.

“Speaker, purpose, audience, context, exigence, choices, appeals, tone. Those are all prescribed by the College Board as part of the AP curriculum, all components of what you need to holistically analyze something,” she said.

Loudon hopes her lesson will help students see how the themes of Wilson’s arguments — race, representation, community, self-reliance, art, identity and more — persist in popular discourse even now, such as in Kendrick Lamar’s 2025 Super Bowl halftime show.

The lesson plan includes an extra credit assignment prompting students to analyze Lamar’s performance and connect its themes to “Fences” and to Wilson and Brustein’s debate.

“I always tell my kids, ‘It all comes back to English class,’ ” Loudon said.