There’s a weed growing in a bucket on Pittsburgh police SWAT Officer Tim Matson’s porch.

It saved his life.

Months after he was shot multiple times responding to an active shooter at the Tree of Life synagogue building in Squirrel Hill, Matson said Wednesday, he remained in a dark place.

Shot in the head, both legs, and arm, he was in constant pain.

Matson, who is about 6 feet 5 inches tall and weighs 315 pounds, knew he’d never be the same.

He contemplated taking his own life.

One day, after his friend had weed-whacked for him, Matson walked outside of his house. He saw a fishing bucket he’d left in his yard.

“There was this weed,” he told the jury.

It was growing in the bucket.

“Man, that’s one tough (expletive) weed,” he said he remembered thinking.

Nobody cared about it, Matson said. Still, there it was growing.

Something struck him.

He remembered all the people in his life who cared about him — even strangers.

“It’s time to get to work,” he said to himself.

As he rededicated himself to recovery, Matson put the weed in water in the bucket. Once it formed a root ball, he put it in potting soil.

And now it’s growing in the soil on his porch.

“I see it everyday,” Matson said.

He was one of five witnesses called to testify Wednesday in the sentence selection phase of the trial for Robert Bowers, the man found guilty of killing 11 people and wounding four police officers Oct. 27, 2018, at the Squirrel Hill synagogue that housed three congregations: Tree of Life-Or L’Simcha, Dor Hadash and New Light congregations who were worshiping at the synagogue that day.

Killed were Rose Mallinger, 97; Bernice Simon, 84, and Sylvan Simon, 86; brothers David Rosenthal, 54, and Cecil Rosenthal, 59; Dan Stein, 71; Irv Younger, 69; Dr. Jerry Rabinowitz, 66; Joyce Fienberg, 75; Melvin Wax, 87; and Richard Gottfried, 65.

The government is seeking the death penalty, while the defense argues their client’s mental illness and troubled childhood mean he ought to be sentenced to life in prison.

The prosecution, which called 22 witnesses as part of victim impact testimony, rested Wednesday afternoon. Immediately, the defense began its case in mitigation, calling an expert in clinical psychology and trauma who conducted a psychosocial history of Bowers, including reviewing 21,000 pages of documents and interviewing 17 of his family members, neighbors and others who knew him.

She spent about two hours on the witness stand, describing for the jury the defendant’s tumultuous family history and chronicling traumatic events throughout his early childhood.

“This is what we could call an extraordinary dose of trauma and risk for someone who’s not yet 2 years old,” said Dr. Katherine Porterfield.

She will return to the stand on Thursday.

‘Will I be normal again?’

Matson, who spent about 30 minutes testifying, detailed for the jurors the injuries he suffered, describing in graphic detail images displayed for them showing his wounds, x-rays and the surgical repairs he’s endured.

He was shot in the head and had to have a surgery to place a drain in the wound.

He was shot in the left leg and had an external fixator — rods and screws drilled into his bones on the outside — to hold it together.

He had the same on his left arm for his shattered elbow and cut tendon.

His skull and jaw were fractured.

He was deaf in his right ear.

His right knee cap was shattered.

He had compartment syndrome in his arm and leg and had to endure a fasciotomy and later skin grafts to try to close the wounds.

“Will I walk again?” Matson said he asked in the hospital. “Will I be normal again?”

On a pain scale of 1 to 10, he told the jury, he was at a 15 or 20.

“It started taking its toll on me,” he said. “Since the incident, I haven’t had a day without pain.”

His new normal, Matson said, is a 4.

After the attack, he spent 16 weeks in the hospital and rehab and another six weeks living in a SWAT team member’s basement because he couldn’t maneuver steps.

He had to learn to walk again. Because he can’t feel below his knee, he had a drop foot. It felt like walking on a flipper, Matson said.

It took him two years before he could return to work. He has had 25 surgeries, and No. 26 is scheduled for after the trial.

In describing the psychological impact, Matson said he goes to therapy — he calls it “happy school” — twice a week.

He cries every day.

“There’s a stigma in law enforcement,” Matson said. “I’m pretty sure nothing about me says weak. I’m in touch with my emotions.”

‘I go one day at a time’

It was the little things that mattered.

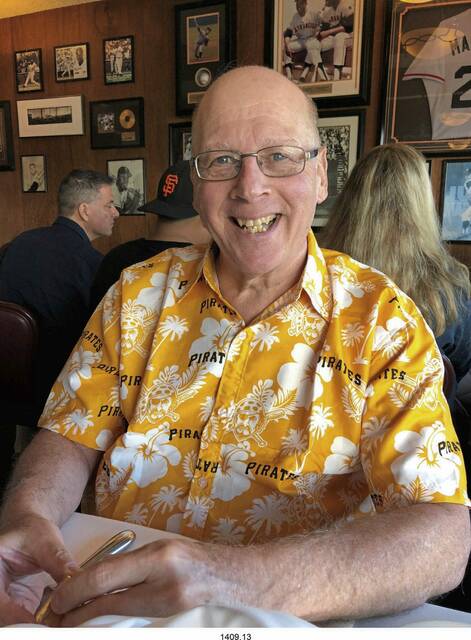

Every day for three years, Dan Stein rose early on Sunday mornings to help his son deliver “The Pittsburgh Press” on his Squirrel Hill newspaper route.

Decades later, Stein, the consummate volunteer, traveled from city to city with his daughter, helping her fundraise for a nonprofit she found immeasurably important.

“The people who knew my dad were the lucky ones,” said his son, Joseph Stein, 45, of Forest Hills. “He’d give you the shirt off his back.”

Joseph Stein testified Wednesday about his father — the kind of man he was and the impact on him after his death.

“A lot of people (say) ‘I don’t know how you’re doing this,’” he said. “I didn’t ask for this. No one asked for this.

“But I go one day at a time.”

Stein, “Danny” to his wife Sharyn, grew up Jewish in Munhall.

He celebrated his bar mitzvah at Homestead Hebrew Congregation, his wife recalled.

On the anniversary each year of that rite of passage, Stein would go to the synagogue and recite the portion of the Torah he read at age 13. He jotted each year inside the prayer book from that milestone.

The Steins moved to Squirrel Hill in 1975. Their daughter was born in 1976, their son in 1978.

“Danny took his responsibilities as a parent very seriously,” Sharyn Stein testified. “He was a helper. … He was always there for (his children) growing up.”

Stein lived to help others.

He worked in outside sales in plumbing supplies by day. On nights and weekends — and more in retirement — he worked at a local food pantry.

He volunteered and served as president, vice president and treasurer of the now-shuttered B’Nai Israel congregation in Pittsburgh’s East End. When the family joined New Light Congregation in Squirrel Hill, Stein became president and led the men’s club there, too.

For the JCC, Stein drove seniors around Pittsburgh to doctor appointments, to the grocery store. He once was named the program’s Volunteer of the Year.

“They became not only people he took, they became his friends,” Sharyn Stein said. “He had a bond with them.”

Stein’s grandson arrived in 2018.

“When my grandson was born, he was just the light of our lives,” Sharyn Stein said.

Now, Joseph Stein looks at his son and sees his father.

“Everything’s a constant reminder of my dad,” he testified. “All the sacrifices my dad made for me, I’m now making for my son.”

Recently, his son asked, “Daddy, do you have a Dad?”

“Devastating,” he said.

‘They never expected to bury their sons’

Michele Rosenthal was on her way to run errands the morning of the attack when her husband got a text message. “Active shooter, Tree of Life synagogue.”

“I screamed, ‘the boys are there,’” she told the jury.

She called her sister, Diane, in Chicago and then called the Achieva home where her brothers, Cecil and David Rosenthal, lived.

Yes, the staff person told her, “the boys,” as they were lovingly called, had gone to services that morning.

Michele said she called her dad in Florida and relayed that something had happened at the synagogue.

She then headed there, just four blocks away. As she got closer to the scene, she testified, she learned that the janitor of the building, who had escaped, saw Cecil on the floor, bleeding from his head.

Michele had to call her dad again. She told him to prepare for the worst.

Hours later, she and her sister went to the airport to meet her parents. As he entered through the terminal gate, Michele said, her dad mouthed a question to her.

“David?”

“I just shook my head, no,” she said.

“He just became hysterical,” she said. “They never expected to bury their sons.”

Michele also told the jury about growing up with her brothers, who had Fragile X syndrome, and as a result intellectual disabilities.

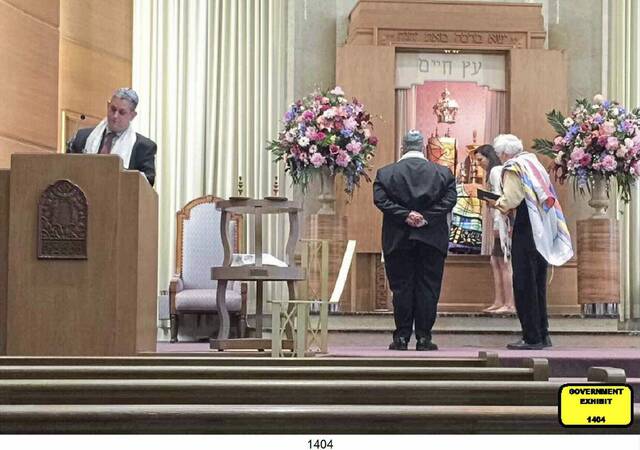

Cecil and David loved going to synagogue.

Even though they couldn’t read, the boys actively participated, and Tree of Life’s rabbi even created “A Need for a Special Shabbat,” a service for those with intellectual disabilities.

Michele said her brothers were so proud to lead the program.

Cecil especially loved removed the Torah from the ark and parading it through the chapel to be touched and kissed by the congregants.

“It was really important to him,” she said.

She called it his favorite thing.

“They had such love for their congregation, Tree of Life,” she said.

Prosecutors played a video of Elie Rosenthal, the boys’ father, talking about his sons.

“It’s been almost five years since I last heard my boys, Cecil and David’s, joyful voices on my answering machine,” he said. “I am convinced that losing a child is the most painful and most unnatural experience any parent could endure.” Elie called the boys “an integral part of our nuclear family.” They enjoyed their lives to the fullest.

“They’re gone forever,” Elie said, holding back tears.

“Our hearts are empty every single day.”

‘It’s not the same’

Andrea Wedner watched Bowers kill her mother, 97-year-old Rose Mallinger.

“I’m haunted by what happened to me and by what I heard and what I saw that day,” testified Wedner, the only person to walk out of Pervin Chapel alive that day. “The hardest part for me is knowing what happened to (Rose), how she died.”

“There’s not a day that goes by that I don’t think about what happened,” she said.

That day, Wedner also watched bullets from Bowers’ AR-15 rifle tear apart her arm. The jury listened to the 9-1-1 call to hear the moment it happened.

On Wednesday, Wedner catalogued the lingering damage.

She’s had multiple surgeries to repair injuries to her arm, at one point patching two wounds with skin from her thigh.

A plastic surgeon in 2019 removed shrapnel from Wedner’s forehead and face. Pieces remain throughout her body; government prosecutors showed jurors Wednesday half a dozen X-rays to illustrate their extent.

Cold temperatures — even a house’s air-conditioning — can cause pain in her arm and hand.

She has another surgery scheduled for autumn. Surgeons hope to get her pinky finger, often number or tingling, to work better.

Wedner used to cover her arms to hide her scars. Now, she has come to term with them.

“I just decided, I have to live my life normally,” Wedner said. “And I don’t mind if people ask me about them … I’m not hiding them.”

Wedner also has other types of scars from the synagogue attack. Independence Day is particularly tough.

“I get startled very easily,” she said. “I know they’re fireworks but the sound of them shakes me to my core.”

Without her mother, Wedner said she has not returned to regular religious services since the shooting.

“It’s not the same,” she said. “I’m having a hard time going every week without her.”

‘I was ready to go’

Dan Leger never thought about ending his own life as he lay for weeks in the hospital recovering from a gunshot wound to his abdomen.

“But I’ve often thought it would have been better if I died that day,” he told the jury.

His death, Leger continued, would have relieved his family of the burden he felt he had become.

A registered nurse who’d worked in hospice and served as a hospital chaplain, Leger spent about 45 minutes lying on the steps of the synagogue after he’d been shot.

Earlier in the trial, he described to the jury his symptoms. He believed he was dying.

His condition, Leger told them Wednesday, was so grave that when he was rushed into surgery from the emergency department, there was so much blood in his abdomen, his doctor had to grab his aorta to try to control the bleeding.

Afterward, Leger was on a ventilator for several days and could not speak. He spelled out words on his wife’s hand to communicate.

“At the points where I was awake enough to be aware of my surroundings, I knew my injuries were serious,” he said. “I spelled out, at one point, ‘let me go.’

“I assumed I was gravely injured or so disabled I would be a burden to her.

“I was ready to go.”

His injuries and blood loss required massive blood transfusions and multiple surgeries.

After several days, Leger said, he was able to be taken off the ventilator. He began to talk to his wife about what happened.

“What happened to Marty?” Leger asked her, of his friend, Marty Gaynor, who escaped the attack.

“He made it,” she answered.

“What happened to Jerry?” he asked.

“He didn’t make it,” she answered.

“What happened to David?”

“He didn’t make it.”

“What happened to Cecil?”

And on it went.

“There was a sense of unreality about the whole experience that was hard to connect,” he said.

Leger learned he had an incision down his midline from his chest to his pelvis. He had a colostomy, which will always remain, from the severe injury to his intestines.

He could not eat and went from about 145 pounds down to 105, and there was a fear he could die from a lack of nutrition.

His pelvis, in particular, hurt a great deal — what Leger called “exquisite pain.

“It was excruciating,” he told the jury.

Leger’s body also filled with fluids — so much so that they were making their own paths out of his body. At one point, after his urinary catheter was removed, the urine inside him escaped through the holes in his abdomen.

He later developed blood clots in his lungs.

Leger was discharged after five weeks but returned to the hospital within a couple of days because of an abscess.

Physical therapy, he recounted, was hard.

“It was so painful to learn to sit first. Then to learn to stand,” he said. “Then to take a couple of steps.”

Before he was discharged, Leger made it his goal to be able to walk down the hall to Matson’s room. He eventually walked in using a walker, Leger said, but he had to be wheeled to the room first.

Psychologically, recovery was difficult, particularly learning to do steps, Leger said. He thinks it might be because of the time he spent lying on the stairs thinking he would die.

Since the attack, he said, he sometimes has nightmares, and he’s more suspicious. Fireworks cause him distress.

Physically, he said his mobility, strength and endurance have not fully recovered. He can no longer be active like he once was, walking Negley Hill to get home.

“By my own standards, it’s disappointing,” he said. “I live with this body that doesn’t feel like it’s mine. I feel like someone took it over and invaded it.”

Leger tried to return to work, but he couldn’t handle the physicality of it. Seeing patients also took an emotional toll on him he’d not experienced before.

“Being in that environment was really difficult,” he said.

Not being able to live how he once did, Leger testified, is hard.

“That really gets me down sometimes,” he said. “I feel very diminished.”

‘I was a terrible mother’

As the defense began its case Wednesday, the first witness used the defendant’s family tree to tell his story.

Katherine Porterfield, the psychologist, traced the branches of that tree into lines and color-coded squares and circles called a genogram, an interpretive map of Bowers’ harrowing lineage.

The defense previously had laid out some of the basics. Bowers’ father, Randall, was abusive and committed suicide. His mother, Barbara, repeatedly was hospitalized for depression. Both parents threatened to kill Bowers when he was just a baby.

His maternal grandmother, with whom Bowers sometimes lived as a child, was an alcoholic, his grandfather abusive.

But Porterfield took that information a step further. Her 23-page report, dated June 17, 2023, attempted to dig deep into Bowers’ family history.

Robert Dennis, Bowers’ great-grandfather, spent 11 years in an Ohio psychiatric hospital, sent all nine of his children to an orphanage, then died from dementia after his brain deteriorated, Porterfield said.

Bowers’ grandmother, Patricia Dennis, was in that orphanage for at least a decade, from 1931 to 1942, she said.

Patricia’s sister Frances was committed to a psychiatric hospital and diagnosed with “manic depression,” then a term for bipolar disorder, Porterfield said. Her brother William got a medical discharge from the U.S. Navy. Two sisters died from dementia. A third overdosed – on alcohol and nail-polish remover – in what might have been a suicide.

Patricia moved to Pittsburgh in 1963, and abused alcohol and drugs. She mixed drinking with Meprobomate, a tranquilizer, and often was “incapacitated” when drunk, Porterfield said.

Her husband, Lloyd, suffered from anxiety and depression, and gambled to the point it strained the marriage. He was physically abusive.

Barbara Jenkins — Bowers’ mother and the eldest of Patricia and Lloyd’s three children — was “a sad, unhappy child,” Porterfield said. She dropped out of high school in 1968 and ran away, ending up at a New York home for troubled girls.

After an unsuccessful bid to attend college, Barbara returned to Pittsburgh and met Randall Bowers, she told Porterfield. Over the span of 12 months, they moved in together, she got pregnant and they married.

Robert, their only child, was born in 1972. The marriage didn’t last a year. The divorce was official Aug. 23, 1973.

“I was a terrible mother,” Barbara told Porterfield.

Jurors were told in previous phases of the trial what happened to Robert Bowers — the fever-induced hallucination at age 5, the suicide attempts, the much-debated schizophrenia diagnosis.

In her testimony, Porterfield cited a massive trauma survey of 17,337 Americans who had health insurance. It found that “for every negative event in a kid’s life … you then saw the outcomes for those kids worsen.”

A child who had experienced three adverse childhood events meant that child was three times more likely to have trouble at school. A score of seven meant a 51-fold increase in the likelihood of adolescent suicide.

Bowers was a seven, she said.

“It’s not that kids can’t have bad things happen – that’s part of life,” Porterfield told the jury. “But you can have severe, repetitive trauma stressors in a kid.”

“Chronic stress changes kids’ developing brains and nervous systems, leading to physical disease, mental illness – and violence,” she said. “That dose of trauma really matters.”