The man contracted to provide more than $300,000 in training for officers at Allegheny County Jail has been the subject of multiple lawsuits, a foreclosure and federal tax liens in recent years, according to documents obtained by the Tribune-Review.

In addition, all four Virginia sheriff’s offices where Joseph Lee Garcia said he previously worked confirmed to the Tribune-Review that he never was an employee.

Garcia, who operates Corrections Special Applications Unit, became the subject of controversy in Pittsburgh when county administration signed a no-bid contract with him in July to provide militaristic training and weaponry to officers at the jail for things such as cell extraction and the use of less-lethal force. In similar training offered by Garcia elsewhere, according to court filings, officers were trained to fire concussive grenades and gouge inmates’ eyes.

Warden Orlando Harper said hiring Garcia’s company was necessary to counter this spring’s referendum banning the use of chemical weapons, leg irons and the restraint chair at the jail.

However, advocates for those incarcerated have argued that Garcia’s training is extreme and violent.

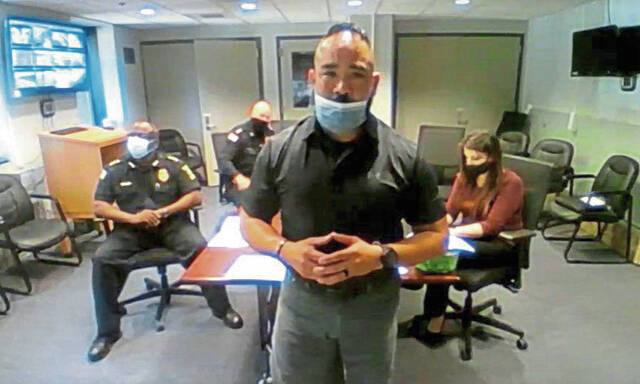

The question of Garcia’s qualifications was raised at this month’s Jail Oversight Board meeting, at which Garcia refused to answer questions about his military service or criminal record.

According to members of the board, neither Garcia, jail administration nor county administrators have provided Garcia’s resume or any of the previous contracts he said he has had with other correctional facilities to them for review. They asked for the documents weeks ago.

“Still, we don’t have any of that information, and that’s just something so incredibly basic,” said Allegheny County Controller Chelsa Wagner, who sits on the oversight board.

Wagner already was leery about the way in which the contract with Garcia was handled. After learning about his background, she said there is no way the contract should be honored.

The cController’s Office said Garcia has been paid $25,000 of his contract, and the county already has paid $20,000 of $93,000 worth of “less lethal” ammunition and $28,000 for shotguns.

However, any additional payment to Garcia has been blocked, Wagner said.

It’s not just about the money, she continued, but also about the contract that impacts the health and safety of Allegheny County residents who are being held at the jail.

“It’s absolutely absurd, but I think what we’re seeing is a doubling down and a failure to respond to fair inquiries and deeper information about someone they shouldn’t have engaged with in the first place,” she said.

A meeting of the jail board is scheduled for Monday.

On Wednesday, Harper refused to answer questions about Garcia’s employment history or his financial problems.

Instead, the warden said the jail sought a contractor for training to allow the facility to comply with the referendum.

“Specifics of Mr. Garcia’s resume, employment history, or financial or legal history are questions for him,” Harper said in a written statement. “We do not make decisions for contracting based on statements or comments, including indication of a person’s political affiliation or personal beliefs, made by those with whom we contract.”

According to Chief Purchasing Officer Frank Alessio, Garcia met the necessary requirements to become a contractor in Allegheny County, including providing tax forms, an insurance policy — typically for $1 million and naming the county as an additional insured — and going through security clearances for the jail.

Messages left for Garcia and an attorney who has represented him in the past were not returned.

Garcia’s employment history

At a meeting of the Jail Oversight Board on Sept. 2, Garcia gave a presentation about his training program. He was pressed by members of the board to provide detailed information about his professional history.

Garcia said his law enforcement work history dated to 1992 and that he has worked for Virginia Beach Sheriff’s Office, Arlington County Sheriff’s Office, Spartanburg County Sheriff’s Office and the City of Richmond Sheriff’s Office.

However, all four departments say Garcia never worked for them.

Arlington County Sheriff’s Department Maj. Tara Johnson said Garcia had never been employed by her department either. He was, however, sworn in there as an “auxiliary” sheriff more than 20 years ago.

In that volunteer position, Johnson said, auxiliary officers do things such as traffic control and help in searches of missing persons.

She said he also provided some training to the department.

“It’s basically like a volunteer program,” she said.

In Spartanburg County, S.C., Sheriff’s Lt. Kevin Bobo said his agency contracted with Garcia years ago for training.

“He was given the honorary rank of captain,” Bobo said. “He was never an employee of this agency, and to the best of my knowledge, he’s not a certified law enforcement or detention officer in South Carolina.”

According to the South Carolina Criminal Justice Academy, Garcia was enrolled in a 120-hour “basic detention” training program from Oct. 31 to Nov. 18, 2016, and graduated with an 86%.

However, on Dec. 5, 2016, Spartanburg County Sheriff Chuck Wright wrote the training center requesting that Garcia’s certification be revoked.

“It has been discovered that a recent graduate for Class 2 LCO Basic Jail Training, Joseph Garcia, does not meet the criteria to have been eligible to receive said training,” he wrote.

Allegheny County Common Pleas Judge Beth A. Lazzara, who sits on the Jail Oversight Board, questioned the vetting process Garcia went through locally.

At the September board meeting, Chief Deputy Warden Jason Beasom said Garcia “went through the jail’s rigorous security checks before being granted access to the facility just like all other contractors who perform work at the jail.”

Beasom said that those reviews included a National Crime Information Center (NCIC) check, and that Garcia has been vetted and granted access to provide training at 52 Law Enforcement Agencies and 14 Departments of Corrections across 35 states.

But Lazzara, upon learning of Garcia’s background, had her own questions, such as “is it a solvent company?”

As for Garcia’s employment background, Lazzara said it is now less than clear.

“When I think, ‘He worked for them,’ I think he was employed by them,” she said. “That, absolutely, is a huge issue for me. It’s a big red flag.”

Corporate records and lawsuits

Public records reveal a number of companies associated with Garcia over the past 25 years.

Two of them, C-SAU 1 LLC and K1K9 LLC, were both incorporated in South Carolina by LegalInc Corporate Services, in 2019 and 2018 respectively.

Garcia’s name is not on the incorporation paperwork for either. However, according to her LinkedIn profile, Garcia’s current wife, Shawna Garcia, is founder and CEO of K1K9. The company’s website shows images of Garcia in a correctional facility with the giant schnauzers he uses in his special operations training.

Joseph Garcia’s name is listed, however, for the previous business he operated, Corrections Special Operations Group, which formed Feb. 12, 2016, as a limited liability company in South Carolina.

Another entity, OPS Group LLC, was established by Garcia’s now ex-wife, Vicki Shunkwiler, in 1996 in Providence Forge, Va.

That company listed its products and services as “Training to Corrections Emergency Response Teams in all levels of jail, prison and penitentiary crisis. Counter terrorism training, high risk inmate transport, close quarter riot control, less lethal munitions, etc.”

Online records show Garcia’s companies have been contracted to provide corrections special operations training at the Henderson County Detention Center in North Carolina in 2018 at a cost of $40,000, and in Weld County, Colo., from 2016 to 2019, at a cost of more than $67,000.

The Weld County training led to a federal lawsuit against the Sheriff’s Office there, after a man said he was injured when officers at the facility shot concussive grenades at him and smashed his face into the floor. Tage Rustgi said in his lawsuit that he sustained a concussion, a laceration to his eye and hemorrhage to his eye.

The complaint names as defendants Weld County Sheriff Steve Reams, the officers involved in the incident and the Weld County Board of County Commissioners.

Garcia and his company are not named defendants, but the 38-page complaint addresses both extensively, claiming that Reams hired Garcia to “assist him in implementing the unconstitutional policies and training, … which are also contrary to any legitimate penal justification, contrary to appropriate standards in the detention setting, and extremely dangerous and unnecessary,” the lawsuit said.

The complaint notes that Garcia promotes and markets Kel-Tech shotguns, which are the same ones that were used against Rustgi. It calls them inappropriate and “extremely dangerous in the jail setting.

“The concussion explosions fired from Kel-Tec Shotguns, as used against plaintiff, create an extremely forceful, deafening blast capable of causing severe injury or death,” the lawsuit said.

Rustgi’s lawsuit also includes complaints similar to allegations raised in Pittsburgh regarding Garcia’s training — that it is designed as though officers are going into combat.

“Joseph Garcia strives to keep his unconstitutional training and policies secretive, as evidenced by public statements falsely claiming his practices are ‘classified,’ when in fact they involve matters of grave public concern,” the lawsuit said. “However, aspects of his training have been leaked publicly. According to jail staff in New York who participated in trainings conducted by Garcia, his motto during training is: ‘Break the jaw and walk away.’ ”

Attorney David Maxted said he could not comment on the Colorado lawsuit. There is a notice on the court docket that the case is expected to settle by October.

Another contract obtained by Garcia’s company — this one with the New York City Department of Corrections — came under scrutiny by that city’s Department of Investigation a few months after it began.

On March 29, 2016, the New York City Department of Corrections entered into a three-year, $1.18 million contract with Ops Group LLC to train the jails’ Emergency Service Unit for dynamic cell extraction, high-risk security patrols, close quarters riot control, CSO battle units, crisis negotiation management operations, correctional officer survival and other areas.

According to documents received from a freedom of information request, the Department of Investigations began investigating the contract three months later after receiving allegations that Garcia did not have the proper credentials to have firearms in New York and that the contract was not properly submitted through DOC’s procurement process.

In a final report dated Jan. 24, 2018, the Department of Investigation found that Garcia and his company were not properly vetted by the Department of Corrections when the no-bid contract was approved. Instead, according to one person interviewed, they did not request Garcia’s resume or credentials, any previous US C-SOG contracts or additional background information, assuming that someone else did.

Another person reported it was standard practice for the New York City Department of Corrections “to only run a LexisNexis check and Google web search of the company and parties involved,” and that any resume, previous work examples or background checks are the responsibility of the “end user.”

“While applicable city procurement rules for this contract would not require background of Garcia’s credentials and certifications, we note this as a vulnerability given Garcia’s involvement in law enforcement training where firearms may be used,” the report continued. “The US C-SOG contract was submitted and approved without sufficient background checks on instructor qualifications and certifications.”

Although the report is heavily redacted, it notes the investigation “did not include any assessment of Garcia and the US C-SOG training performance under the contract or assessment of the curriculum in which he taught to DOC ESU staff.”

During the investigation, the report said, Garcia “provided a folder of documents pertaining to his background, credentials and previous contracts US C-SOG had with other correctional facilities” during a Sept. 6, 2016, interview with the Department of Investigation.

However, it continued, “At no point did DOC review Garcia’s credentials before awarding the contract.” Because Garcia provided the above documents and made the above representations after commencing the contract with the DOC, DOI draws no conclusion as to whether Garcia actually misrepresented his qualifications to DOC. However, we include these findings for your information and consideration of how background verification in connection with DOC contracts can be improved moving forward.”

It is unclear if the contract ultimately was canceled. Multiple messages for the NYC Department of Corrections were not returned.

In Charleston County, S.C., county council in July agreed to pay $10 million to the family of a man who died following a cell extraction at the detention center.

Jamal Sutherland died Jan. 5. According to a report from the Ninth Circuit Solicitor’s Office, the facility received training from Garcia and US C-SOG from 2008 through 2019 when training moved in-house. However, according to the report, the facility still subscribes to the substance of that training.

At the September Allegheny County Jail Oversight Board meeting, Garcia said his company had stopped providing training at the Charleston County detention center in 2018, and that the two officers involved in Sutherland’s death never graduated from the C-SOG training program.

“We have not been named in any lawsuit,” Garcia said. “We have cooperated fully with the FBI, who took all of our information that we provided to them. We changed the mental health program, but everybody involved in the Jamal Sutherland (case) had nothing to do with our organization, our training, period. End of story. Those are the facts.”

Financial troubles

Public records paint a picture of Garcia as having substantial financial problems.

On June 8, 2011, a $60,089.85 lien was filed against the Garcias by the Internal Revenue Service in Williamsburg City Circuit Court for the tax period ending Dec. 31, 2009.

Another $45,446.58 federal tax lien against the Garcias, for tax years ending in 2003, 2004, 2005 and 2007, was released by the IRS on Sept. 3, 2009, as having been satisfied.

Then, in 2016, according to federal court filings in the Eastern District of Virginia, the Garcias sought a $125,000 loan from their friends, Nicholas and Pamela Trbovich.

According to a lawsuit, “The Garcias represented to the Trbovichs that they needed the money in order to pay back taxes they owed to the IRS and/or state tax authorities.”

The Garcias agreed the money would be paid back within 90 days, the complaint said. If it was returned within two weeks, there would be no interest charged. After that, the interest rate would be 10% per annum.

Although the Trboviches wired the money to Joseph Garcia at Towne Bank on April 20, 2015, the complaint said, it still had not been repaid by May 2016.

According to one filing in the case, Vicki Garcia said she and her husband were separated at the time, that she did not participate with him in any dealings with the Trboviches and was not a party to the loan.

A federal judge entered default judgment on Oct. 20, 2016, noting that neither defendant had filed an answer to the complaint against them. However, in a document docketed April 23, 2019, the attorney representing the Trboviches said his clients had agreed to accept — and had already been paid — from Joseph Garcia “a sum of money less than the full amount of the outstanding judgment.”

In 2018, according to assessment records from New Kent, Va., the home the Garcias had purchased in April 2007 in Kents Store, Va., for $536,000, was foreclosed. Records show it was bought for $374,840 by U.S. Bank National Association.

Wagner, Allegheny County’s controller, said she is bewildered by the findings.

“This shouldn’t have been under consideration to start,” she said.