Alicia Dallago had no clue that the McCandless home she bought in 1998 represented a unique slice of American history.

She was just enthralled by the way it looked and made her feel when she stepped inside.

“I loved the antique look and quality of the house,” said Dallago, 79, a native of Argentina who moved to the U.S. in the 1970s. “I never heard of Sears mail-order houses until I began talking to neighbors who told me that’s what my home is.”

Decades before the internet made it simple to click and ship items to your door, shoppers could do just about the same thing using mail-order catalogs.

Beginning in the late 1800s, retailers such as Sears, Roebuck and Co. sent out fat catalogs filled with everything from sewing machines and saddles to bicycles and baby buggies for sale.

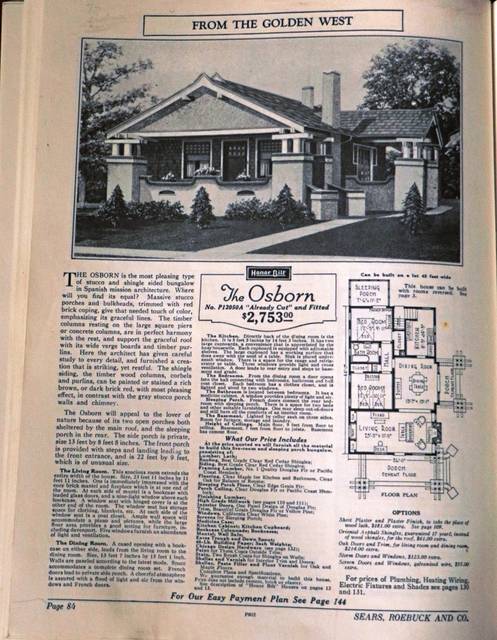

The company not only sold all a family could need to furnish a home, between 1908 and 1940 it sold the house itself — a kit delivered to your nearest railroad depot containing thousands of parts needed to construct a home.

During that period, Sears sold nearly 75,000 kit homes through its Modern Homes program, which featured 447 different styles of houses ranging from large multi-story dwellings to tiny summer cottages with an optional outhouse.

Dallago said once she found out that her home — an “Osborn” model built in 1922 — was a Sears mail-order house, she was intent on preserving and restoring its historical character.

“It still amazes me that so much of the original house was unchanged,” she said. “The windows and storm windows still have the original ‘wavy’ glass that was used back then and the hardwood floors, 8-inch baseboards and the woodwork have not been painted or modified in any way.”

The home features Spanish mission-style architecture finished in stucco with red brick trim and accents. The front porch features wood columns resting on large concrete and brick piers.

Dallago’s house also has a sun porch attached to the dining room that she says “is my favorite place in the house to spend time.”

While the electrical, plumbing and heating systems have been brought up to modern standards, remnants of the early knob-and-tube wiring are still visible in the basement, which also contains the original coal-fired boiler that provided steam heat to the home’s radiators.

All the original glass doorknobs, doors and other architectural touches such as the “craftsman” style roof overhangs and pillars also remain.

The coal cellar has been sealed off to keep drafts out, but Dallago said there were still chunks of the fuel in the room when she moved in.

Sears was not an innovator in home design or construction, according to the company’s archives. But it did use innovative mass-production techniques for its materials to reduce the cost of homeownership.

Kits were delivered with thousands of parts, stamped with numbers and an instruction book so buyers could build their homes with little or no help from outside contractors.

The company even sold separate kits for electrical, plumbing and heating systems along with a $12.50 device used to create the cement blocks needed for the foundation.

Sears also used a framing system that did not require a team of skilled carpenters. Easy to install drywall replaced traditional lathe-and-plaster walls and asphalt shingles were used to reduce labor costs.

Andy Masich, director of the Heinz History Center in the Strip District, said homes from the past can provide a snapshot of daily life.

“The architecture of our region gives us an insight into the people who preceded us,” he said. “And that architecture includes grand office towers right down to kit homes that families could assemble themselves.”

Masich commends efforts to preserve buildings that have historical significance.

“Whether or not a home is eligible for the National Register of Historic Places, there is value in preserving the built environment,” he said. “These homes are a touchstone to the past.”

Whenever possible, Dallago has replaced modern features such as light fixtures with items more befitting the age and style of the house.

She also has furnished it with antiques from the period in which the home was built to create a true snapshot of what the home would have looked like during the early 1920s.

Sears no longer has records of where all of its mail-order homes were built, but a number of them have been identified in the Pittsburgh area, including in North Huntingdon and Murrysville Community Park.

Dallago said while restoration and maintenance of a nearly 100-year-old house like hers can sometimes be frustrating and pricey, it’s worth it.

“I believe these homes are a part of America’s history, so I’m going to do everything I can to keep it the way it is,” she said. “I feel it’s the right thing to do.”