Editor’s note: This is Part 2 of a two-part series on Massey Harbison by the Richland History Group. Part 1 appeared in the May edition of the Pine Creek Journal and is available online.

Last month’s Part 1 of 22-year-old Massey Harbison’s agonizing, six-day, 70-mile journey through the Pine and Richland areas (after her early-morning capture in May 22, 1792, by Native Americans from her and husband John’s cabin in Freeport) ended with her witnessing 1) the Native Americans swinging Samuel, her 3-year-old son, by his feet, such that his head hit the cabin’s doorframe until his “brains were dashed out” and 2) his scalping. This was done because Samuel had been crying. Here is an account of her horrifying journey after this killing.

Later that May 22, Massey endured a second unfathomable horror while being taken toward a Lenape (Delaware) encampment at Salt Lick, 5 to 6 miles north of Butler. Slate Lick was named because deer licked salt from the slate rock there. Her 5-year-old son, Robert, complained to his Indian captors about an injury from falling off a horse that rolled down a steep embankment, probably near Buffalo Creek.

Massey watched his tomahawking — she later said stabbing — death and subsequent scalping.

She later gave the following chilling account of this murder: “One-year-old John is in my arms as Robert is killed, his scalp displayed bright red before my eyes. Once again, I am beaten into action. The cold water (probably Buffalo Creek, but possibly the Allegheny River) brings me to my senses! This is no dream, but a living nightmare.”

In another account, she wrote that “I saw the scalp of my dear little boy, fresh bleeding from the head, in the hand of one of the savages, and sunk down to earth again.”

Following Robert’s killing, the group of Native Americans, with captured Massey and infant John in tow, continued westward more or less along today’s Route 422 until reaching the Mt. Chestnut area, just west of Butler. A Delaware captor took Massey as his squaw.

Massey, six-months pregnant, stayed there a day with John. While her captors slept in the early May 24 morning (a half-hour before sunrise), Massey escaped, all the while carrying infant John.

Without a compass but with trail insights she had learned from her husband, a woodsman and Indian military spy, Massey trekked purposely in the wrong direction, hoping to fool the Native Americans, who would certainly be after her. She quickly realized that she needed to bear southeast to get back to the Allegheny River.

Barefoot, with skin hanging in strips, in constant pain (her feet hurting badly from thorns), hungry and starving, she used the stars and sun to head southeast and crossed Connoquenessing Creek.

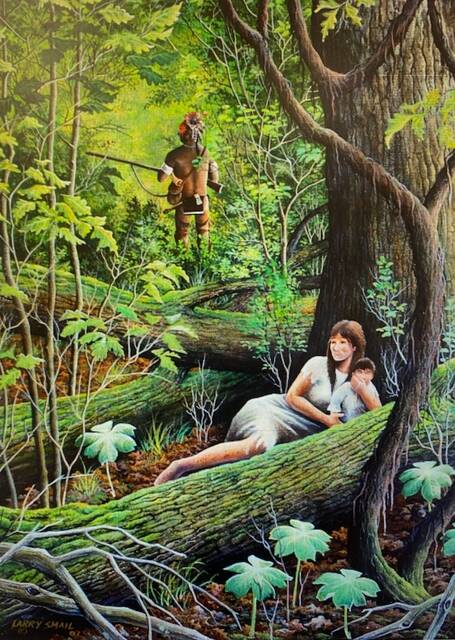

Massey became aware of a man following her. As she prepared to sleep on the fourth night, May 25, near today’s Mars Middle School in Middlesex Township, young John began to cry. She looked for a place of cover and hid with John behind a nearby tree.

A Native American went right to the spot where John had been crying and stayed there motionless — on alert with his rifle. He was unaware of Massey and John’s close proximity behind the fallen tree. She could barely breathe, lest the pursuer discover her, and she could only pray that 1-year-old John would not wake up and begin crying.

The man stayed motionless for two hours, suspecting Massey was in the area. Suddenly, after what seemed like forever, Massey heard a distant bell and a cry like that of a night owl. The nearby Native American responded with a yell and, to Massey’s great relief, suddenly retreated north. In honor of Massey’s endurance and bravery, Harbison Road heads north today off Route 228 in Middlesex Township, just south of the Mars Middle School campus.

From the Mars Middle School area, Massey continued southeast, passing Valencia. Some historians suggest that after Massey had been hiking southeast to the Mars Middle School area — a high point on a ridge — she suddenly went off the ridge, turning west on Route 228 and headed downhill to the intersection of Route 228 and Mars-Valencia Road, a low point.

This seems highly unlikely, as Massey would have been turning away from her desired southeast direction. Also, Massey’s husband, a woodsman, would have instructed her to stay on ridges, as Native Americans did, to minimize travel time. Based on this, the Richland History Group is almost certain that Massey would have stayed on the ridge from the Mars Middle School and ventured from Three Degree Road (Middle School) to Ridge Road (just east of Valencia) to State Road, crossing Bakerstown Road onto either Grubbs Road and then Hardt Road in Richland or Hillcrest or Meridian roads in Richland and continued southeast to the Allegheny River at Fox Chapel.

As Massey headed southeast on May 26, she saw the flash of a rifle probably somewhere in today’s Hampton area, and she hid, only to find that her hand was near a group of rattlesnakes. That convined her to keep moving, notwithstanding the possibility there were Native Americans nearby. On May 27, she recognized Squaw Run — renamed Sycamore Run in 2023 — which she followed to the Allegheny River and to safety where the Fox Chapel Yacht Club stands today.

So tattered was she that James Clothier, a colonist neighbor who knew her well, did not recognize her “by her voice or countenance” when he rescued her on the Allegheny River in Fox Chapel. Her skin was raw from sunburn. One hundred fifty thorns were removed from her feet and legs. Her flesh was “mangled dreadfully.” She was taken by canoe to Fort Pitt at today’s Point State Park in Downtown Pittsburgh, where she gave testimony to Pittsburgh Magistrate John Wilkins regarding her nearly six days and six nights of nearly naked travail.

Massey had a second encounter with raiding Native Americans. She and husband John moved their family after her successful 1792 escape to a cabin near Craig’s Station (Buffalo Creek) on the Native American side (west) of the Allegheny River. In May 1795, at the very end of the Northwest Indian War, five women and 13 children successfully escaped another raid while their husbands were away on military duty by crossing the Allegheny River to a safe blockhouse on the river’s east side.

Harbison had six more children, but her husband abandoned her for unknown reasons in 1819. She died in 1837 at age 67 and was buried in the old graveyard on Fourth Street in Freeport. In 1942, the Daughters of the American Revolution dedicated a 4-ton monument with a bronze plaque in memory of her capture at Logans Ferry Presbyterian Church in New Kennsington.

Mary Jane Harbison, a woman to be reckoned with, is likely the greatest of all colonial heroines. Her fortitude, resiliency and bravery during unthinkable tribulation is inspirational. Today’s Richland and Pine townships are proud to have had her on their soil.