They are called the “hibakusha,” the survivors of the atomic bombs that fell on Hiroshima 75 years ago today and on Nagasaki on Aug. 9, 1945.

Their stories are hard to hear. One survivor visiting Boston in 1985 for Hiroshima’s 40th anniversary reduced a group of reporters to tears.

The man remembered that Aug. 6 began as a beautiful, clear summer day in Hiroshima. He saw the plane that dropped the bomb, releasing a white object that fell toward the ground. And then, moments later, there was darkness. He said he lost his hearing and, as he stumbled around, he saw charred bodies and burned and bleeding survivors.

An estimated 140,000 Japanese citizens died that day.

In the 75 years since President Harry Truman decided to drop the atomic bombs in order to end World War II and avoid an American invasion of Japan, there has been debate about whether it was the right thing to do.

But area World War II veterans who spoke with the Tribune-Review will have none of it. They are convinced Truman’s decision not only saved their lives and those of thousands of other American troops, but the lives of Japanese soldiers and civilians as well.

Anxious for combat

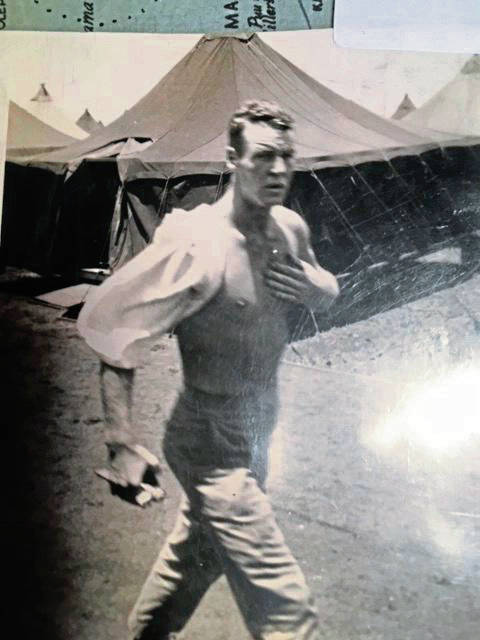

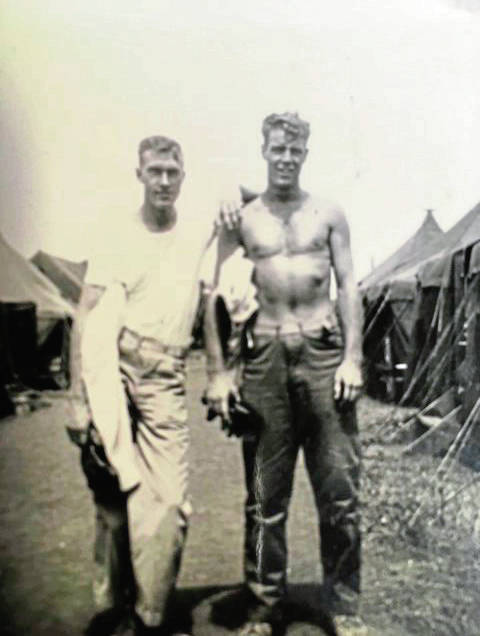

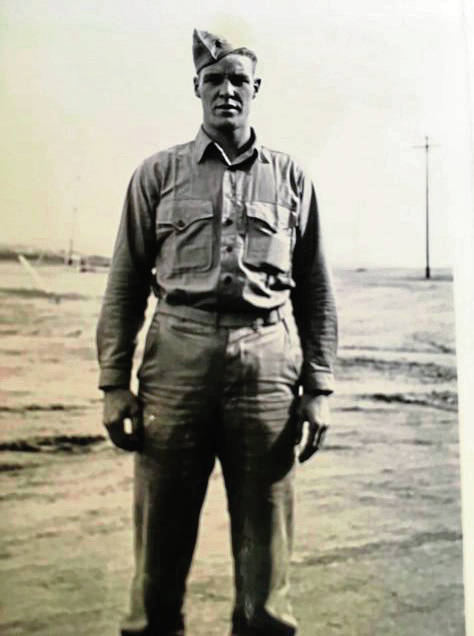

Jack Watson was the kind of Marine who belonged on a recruiting poster. Sturdy and Hollywood handsome, Watson joined the Marines on Dec. 7, 1942, exactly one year after the Japanese sneak attack on Pearl Harbor.

Watson, who grew up in Pittsburgh’s Morningside neighborhood and graduated from St. Vincent Prep in Latrobe, had started college at Penn State when, at 18, he realized he didn’t want to be there.

America’s involvement in the war was well underway and Watson wasn’t going to wait to be drafted.

“I just thought the Marines were a great branch of the service,” said Watson, now 96 and living in Pittsburgh. “They had been fighting in the South Pacific. I wanted to volunteer to do something. I was at Penn State from September 1942 until November of that year and then I enlisted in the Marine Corps.

“I wanted to get into combat, which was dumb,” Watson said. “Now I know how dumb that was.”

Watson was assigned to the 4th Marine Division and rose quickly through the ranks, becoming a sergeant. He ended up on Iwo Jima in one of the bloodiest battles of the war.

The island proved tougher to take than the Americans had anticipated. The 4th Division was part of the initial landing and took heavy casualties. After having been told that he probably wouldn’t see combat, Watson was called in as a replacement on the second day of the invasion and led 37 men into battle on Feb. 19, 1945.

“A lot of people in command were lost and they needed men. We saw hand-to-hand combat on the first day and were there fighting for nearly a month. I turned 21 there and didn’t even realize I had a birthday,” Watson said.

After Iwo Jima was secured, the 4th Division went to their home base in Maui to train for an invasion of Japan. Watson said it was something they dreaded.

“We knew what we were training for and we weren’t happy about that because we knew that we were never going to come out of there alive,” Watson said. “So, when the (atomic) bomb was dropped, we were elated. It saved us from almost certain death. If we had to invade Japan, the 4th Division would have been wiped out in the initial invasion. And we knew that. We were training to die.

“We really celebrated after the bomb was dropped because we were told we didn’t have to fight anymore,” Watson said. “In my estimation it was a godsend.”

‘The first thing I thought of was my girlfriend’

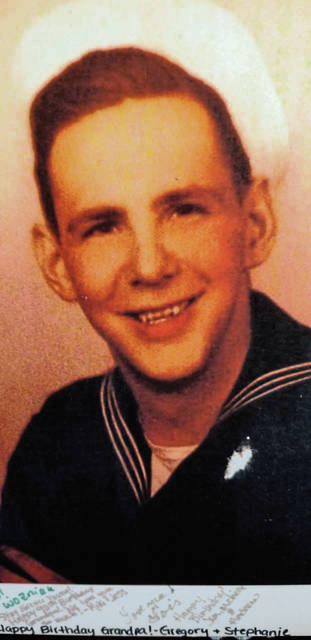

Bob Young, 94, Bethel Park, was a 19-year-old Navy radio operator who spent three years in the Pacific aboard the USS Logan. His job was to decode secret messages from the American command.

Young had the good fortune to draw the long straw when it was time to pick radio operators to go ashore at Iwo Jima. He ended up being able to watch from the ship as Marines raised the American flag atop Mount Suribachi. He also survived a storm that nearly sank the Logan.

“I was very lucky,” said Young.

When Young and his shipmates heard the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, they realized they would soon be going home.

“The first thing I thought of was my girlfriend back in Pittsburgh. We had been writing quite a bit and I couldn’t wait to see her,” Young said.

Young said he has never wavered in thinking that dropping atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki was not only a good thing for the United States, but Japan as well.

“I think it saved more lives than it took,” Young said. “If (U.S. troops) would have landed on Japan, it would have been a pretty terrible battle. A lot of Japanese people would have been wiped out and a lot Americans would have been wiped out.”

‘We couldn’t comprehend it’

Bob Brodine, 94, of Allison Park, was part of a Navy aircrew in the Pacific, a 1st class petty officer and radar operator whose job was to jam the enemy’s electronic transmissions.

Brodine’s older brother Jack was serving in the Army at the same time. Unbeknownst to Bob, Jack was servicing the electronics equipment on the Enola Gay, the B-29 bomber that dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima. Bob didn’t find out any of this until after the war was over.

“I had no idea where he was or what he was doing,” Brodine said. “We didn’t know the potential of it. We really didn’t know how powerful it was. We didn’t know anything about it. The question we were asking was ‘when are we going to invade Japan?’”

Watson said none of his fellow Marines were aware that an atomic bomb was being developed until it was dropped.

“Like everybody else, we couldn’t comprehend how one bomb could be that powerful. I couldn’t envision one bomb that could wipe out entire neighborhoods, entire cities,” Watson said.

When asked if the United States did the right thing by dropping the bomb, considering the high civilian death toll, Watson did not hesitate.

“I know it took a lot of lives, but that’s what had to be,” said Watson.

Brodine said it was no different than bombing a ship.

“We weren’t bombing the ships to kill the people, we were bombing the ship to get rid of the ship. It never registered emotionally with us,” Brodine said. “We were aiming at a target and if there were people there, it didn’t matter. I know that sounds rather cruel, but you shouldn’t be involved in war if you are worried about killing people.”