Allegheny County is confronting among the biggest outbreaks of hepatitis A in Pennsylvania, and illegal opioid use could be part of the reason why the vaccine-preventable liver infection continues to spread statewide, state Health Secretary Dr. Rachel Levine said Monday.

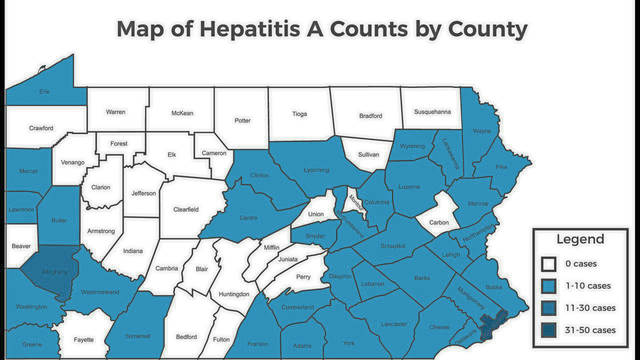

Since January 2018, the state confirmed at least 171 hepatitis A cases across 36 counties, with the bulk in Western Pennsylvania and in the Philadelphia area. That’s up from 91 cases reported as of early December.

At least 23 cases — or 13.5 percent of all incidents statewide — have involved patients in Allegheny County, up from eight reported as of December, according to Ryan Scarpino, spokesman for the county health department.

Butler, Washington, Westmoreland, Greene, Somerset, Lawrence and Mercer counties each have observed between one and 10 cases, according to state data.

Levine has issued an official outbreak declaration, which could free up federal funds to help the state provide more vaccines.

“The counties hardest hit by this outbreak are Philadelphia and Allegheny, but we have seen an increase of cases throughout much of the state,” Levine said in a statement. “We are taking this action now to be proactive in our response to treating Pennsylvanians suffering from this illness and prevent it from spreading.”

State and county health officials announced in November they were investigating a spike in cases of hepatitis A in southwestern Pennsylvania.

Neighboring states have been even harder hit, with more than 2,000 cases confirmed since the start of last year in Ohio and West Virginia, Levine said.

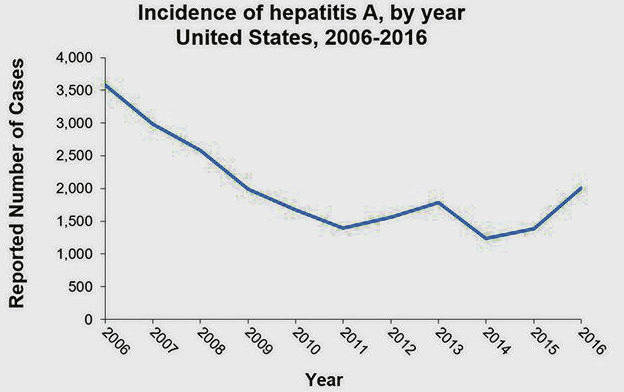

The outbreaks follow years of hepatitis A incidence declining since its vaccine became available in the mid-1990s.

Among other states that have experienced outbreaks since spring 2017: California, Arkansas, Alabama, Indiana, Kentucky, Massachusetts, Michigan, Missouri, North Carolina, Tennessee and Utah.

Levine said that “it’s hard to know for sure why we are experiencing an outbreak.”

“We do know that the Commonwealth has seen an increase of diseases like hepatitis A and HIV because of the opioid epidemic,” Levine said.

Drug users who use needles to inject illicit substances are among those most at risk, along with people who are homeless or encounter someone who has the virus.

At least six local hepatitis A cases involved drug users, the Allegheny County Health Department said.

The hepatitis A viruses cause a highly contagious liver infection that can last from weeks to months.

Unlike hepatitis B and C, hepatitis A typically does not result in chronic illness or lifelong problems. In rare cases, the disease can cause liver failure and death.

Symptoms of hepatitis A, which typically take 15 to 50 days to appear, can include fever, fatigue, loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, dark urine, diarrhea, clay-colored stool, joint pain and jaundice. People who are older than 50 or have liver disease are at risk of developing more severe problems.

The disease spreads when the virus is ingested from objects, food or drinks contaminated by small, undetectable amounts of stool from an infected person. Hepatitis A also can spread from close personal contact with an infected person, such as through sex or caring for someone who is ill.

The best way to prevent hepatitis A is by getting a vaccination, Levine said.

Officials also recommend frequent hand-washing before and after preparing food, after using the toilet, changing diapers, touching garbage or caring for someone who is sick.

The county health department’s Immunization Clinic offers free hepatitis A vaccinations to under- or uninsured residents, as well as to county residents who are at high risk for contracting hepatitis A. For more information, call 412-578-8060.

A map of vaccine clinics is available at the state health department’s website. Visit health.pa.gov for more information.