There may be no one in Pittsburgh who knows more about graffiti than city police Detective Alphonso Sloan.

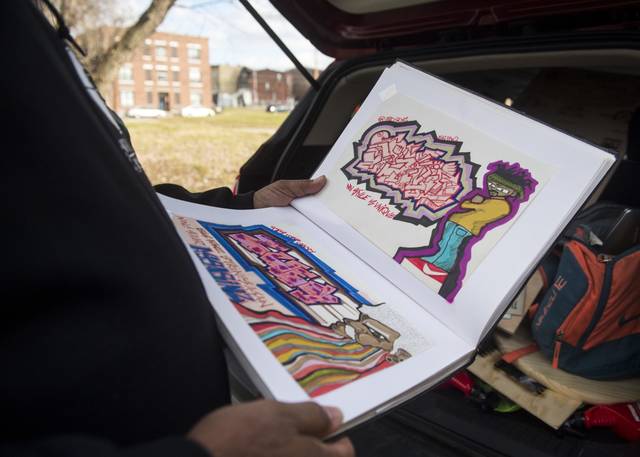

Sloan, the lone detective on the city’s Graffiti Task Force, is himself an artist. He has a deep appreciation for what he sees in the talent displayed by many of those who feel compelled to tag walls, bridges and buildings with visual expressions of themselves.

After all, he was a graffiti artist himself, known as FONZ during his somewhat rebellious teenage years in Pittsburgh’s Garfield neighborhood.

“I was always interested in graffiti,” Sloan said, adding that he used to make trips Downtown and would walk the bridges just to admire the graffiti. “The talent is unbelievable.”

Sloan, a 1989 graduate of Peabody High School, spent countless hours honing his craft with other middle and high school art class students. They ran around in graffiti crews such as TVA or The Versatile Artist, and YFA, Young Fresh Artist.

Joining the force

Sloan said he was never arrested. He eventually grew tired of the thrill-seeking that ispart of the world of graffiti artists and taggers. Evading cops is part of the rush.

“I know if the cops pull up, I gotta run. It adds a whole new dimension,” Sloan said. “If someone gave permission, there would be no excitement.”

Sloan put aside his spray cans and started painting clothes.

“Making money off my talent instead of being chased around by police,” said Sloan, a 1993 graduate of the Art Institute of Pittsburgh. “To this day, I still do a lot of graphic design and visual art.”

As intense as his passion for artistic expression was, there was also something else in his DNA he could not ignore.

“Both of my parents were police officers,” Sloan said.

His mother, Shirley Sloan, was a city police officer for 36 years. His stepfather, the late Grinage Wilson, was a Housing Authority police officer. In 1995, Sloan continued the family legacy and became a member of the Pittsburgh police force.

Sloan said Pittsburgh’s graffiti problem had gotten out of hand. In the early 2000s, taggers such as the legendary Michael Monack, known as Mook, and his Value Krew, or VK, hit city landmarks such as the tops of bridges, buses and city vehicles — including a truck used to clean up after the vandals.

Monack was eventually arrested, sentenced to jail and ordered to pay restitution and do community service. He retired from tagging and opened up a tattoo shop on the South Side.

In 2006, the police formed Pittsburgh’s Graffiti Task Force. Sloan joined the then-three-person squad a few months later.

It was disbanded in 2012 but reinstated by Mayor Bill Peduto in 2015. It is a task force of one now, and the mayor is not planning to expand it.

“The mayor believes one detective is enough, especially since Detective Sloan is doing such a great job,” said Tim McNulty, a spokesman for the mayor.

McNulty said the graffiti issue in the city has gotten better since Sloan took over. Numbers are down, and Sloan is proactive in his approach, McNulty said. Peduto reinstated the task force to acknowledge the impact graffiti can have on someone’s quality of life.

“This year, we even changed the City Code to give him more power to issue citations to private properties that have graffiti that has not been cleaned up,” McNulty said.

A tough beat

Battling graffiti isn’t easy. Monack, in a 2004 interview with the Trib, said it is like terrorists.

“Graffiti is always going to be there,” Monack said at the time.

Sloan acknowledged the difficulty. He said police basically have to catch taggers in the act to get a conviction. And that’s hard.

“Most operate under the cover of darkness,” Sloan said. “They come out at night dressed in dark clothing, a hoodie and a backpack. Those are the guys I’m looking for.”

But who those guys are is hard to pin down. Sloan said taggers and graffiti artists don’t fit into neat gender, race, age or other demographic categories.

Most are men, but there are some women who tag, Sloan said. Many are teens, but some are in their 40s.

“It crosses all racial boundaries. There’s been a pretty big surge in racist graffiti since Trump became president. (Both) Nazi stuff, (and) anti-white stuff,” Sloan said. And there’s a difference between taggers and graffiti artists with talent, Sloan said.

“Most of the guys are just taggers. A graffiti artist has artistic talent (and) typically paints murals,” Sloan said. “Taggers don’t have any skill — just a need to put (their) name on something, just to be seen.”

There’s no way of knowing exactly how big of a problem graffiti is, Sloan said. He receives about 40 to 50 reports a month, but the vast majority go unreported.

“It’s a non-violent crime. People don’t like to call 911 for non-emergencies,” Sloan said. “I encourage people to call 911 to report graffiti on their own property or if they see someone in the act.”

Those who see graffiti in public places should report it on the city’s 311 response line, Sloan said.

Sloan makes an average of one or two arrests each month.

“A little more in the summer,” he said. “They don’t tag as much in the winter because spray paint freezes up.”

Channeling the art

Sloan works with Graffiti Busters, a Pittsburgh program that cleans up graffiti once someone reports it. If the graffiti is racist or vulgar, they head out right away, Sloan said.

“Any business owner or resident can utilize the program as long as they make a police report,” Sloan said.

The clean-up costs are steep — several hundred dollars for each square foot of ground-level graffiti and several hundreds of dollars more if workers have to use a lift truck.

Former Steelers running back Baron Batch, a Homestead artist and entrepreneur, had to pay paid tens of thousands of dollars in fines, court costs and legal fees after admitting to painting colorful murals in 2016 on the section of the Three Rivers Heritage Trail that runs along the Monongahela River between the Hot Metal Bridge and Sandcastle. Sloan arrested Batch, but that didn’t stop the two from liking and respecting each other.

In 2017, they collaborated on an art program at the Space Gallery in Downtown. In a video posted to the Pittsburgh police’s Facebook page, Sloan and Batch joke around with five kids from the city’s Learn and Earn program that helped on a mural project. Batch says in the video he’s helping the kids see what it is like to be a creative entrepreneur.

“You’re not supposed to do that so I got arrested,” Batch says in the video about the art he painted along the trail. “This guy (Sloan) came and got me. You showed me those photos, and I said, ‘Yeah I’m guilty of that.’ ”

Batch, who declined to be interviewed for this story, said in the video that even having the kids see Sloan and him working together makes a statement.

“I think it’s good for kids to be around law enforcement because everybody is just people,” Batch says.