It’s mid-afternoon. You’re in your home office when the laptop pings to remind you of the daily meeting starting in five minutes. If it’s a video call, you make sure your face is presentable. Maybe you slip on a work shirt and smile, knowing they’ll never suspect how your bottom half is clothed.

You join the virtual meeting space and suddenly your speakers are alive with the sound of co-workers and bosses.

It’s the digital conference call — the technology of choice during the coronavirus pandemic, as millions worldwide are working from home.

Would you believe a man from Pittsburgh’s Point Breeze neighborhood made it all possible?

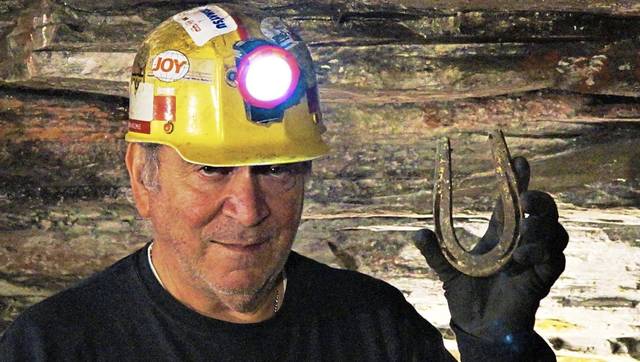

His name is Giorgio Coraluppi, an 86-year-old Italian immigrant who lives in the same house that he bought in 1976. He came to the U.S. in 1964 with his wife, Luisa, to whom he’s been married 57 years. He walks with a walker and talks — slowly and deliberately — with a deep accent.

Uninterested in retirement, he daily leads his approximately 650 employees of Chorus Call, Compunetix and Compunetics from his Monroeville office with the same voracity of a “40-Under-40” leader. They call him “Dr. C.”

Coraluppi is an engineer, a mathematician and an inventor who in October will be inducted into the Space Technology Hall of Fame for inventing the set of computer codes powering the technology that’s keeping the world connected these days: the digital teleconference call.

The technology — an algorithm supported by a computer chip — was first designed for NASA. It has spawned a global industry that helps people communicate more effectively.

Behind this half-century of innovation, there is a man who talks of his career thus far in abstract anecdotes that, when seen altogether, illuminate a character unwavered by the risk of failure and buoyed by a seemingly unquenchable drive to solve problems.

Good vs. Bad

On a recent morning in his office, Coraluppi demonstrated his philosophy of entrepreneurial risk-reward. He grabbed a piece of paper and drew a cross.

On one side, he wrote “Good,” on the other, “Bad.” Under the “Good” column, he scribbled a bunch of squiggly lines as he vocalized hypothetical achievements until the column was full of squigglies.

In the “Bad” column, he drew one squiggly line. He paused for effect, then drew a definitive “X” through the entire “Good” column.

“One mistake can wipe away all the good your company does,” he said.

But making mistakes does not have to mean failure. For this inventor, as long as he comes out with what he calls “an enhanced set of professional capabilities,” he’s satisfied. Those “professional capabilities” can serve as foundational knowledge for the next project.

The honey woman

One of the earliest risks Coraluppi took was when he was 10 years old. One day in 1944, he was riding a bicycle through his Italian hometown, L’Aquila, when he came upon a “strange alley.”

“And I wanted to test myself: How long could I drive with closed eyes?” So he did. The experiment ended when he ran into a woman carrying a load of honey on her bike. The impact caused her to spill it all, wasting it.

“She was furious,” Coraluppi remembers. “She raised hell with me.”

The young, questing boy couldn’t fully grasp the depth of the honey woman’s anger. But it didn’t take long to get a clue. Italy was in the middle of war. Food and other goods were scarce.

The honey woman demanded that the reckless boy take her to his parents. They must learn of this grave crime. When she briefed his father, he soothed her by giving her kitchen salt, a valuable commodity at the time.

It was his father’s example of preparedness that helped shape an ethic in Coraluppi which later helped his business thrive.

And the run-in with the honey woman perhaps began a lifetime of innate curiosity.

‘We can do that’

Coraluppi married Luisa in 1963, while still living in Italy. By that time, he had graduated from a technical school in Milan with a doctorate in electrical engineering and served a year-and-a-half in the Aeronautica Militare, the Italian Air Force. Service in Italy’s military at that time was mandatory — but it was there that his interest in the technology behind communications sprouted.

About a year into the marriage, the couple packed everything and moved to America, the land of opportunity. They landed in a house in Gibsonia that they rented for about two years.

While here, he worked for the American Optical Company in its endeavors with NASA. His role was to engineer a program that controlled the NASA-Lewis Flight Simulator and other space-related projects.

Three years after immigrating, Coraluppi enrolled at Carnegie Mellon University to “freshen up” on his education, a sort of intellectual curiosity. He never intended to graduate, but he did, earning a master’s degree in electrical engineering after being nudged by a professor to complete the coursework and exams.

The collegiate experience exposed him to the nascent world of computer chips, which were just beginning to take hold of the electronics industry. The microchips had an endless appeal, and a promise to keep bringing new opportunities, both commercially and intellectually.

While a student in 1968, he founded Compunetics Inc. alongside two others from CMU in a rented space behind an ice cream parlor along Saltsburg Road in Penn Hills.

The idea behind the new business was idealistic and open-ended. In fact, the company didn’t even have a five-year plan, said Robert Haley, Compunetix’s director of marketing.

“It was really to go after complex problems and solve them electronically. It was like (Coraluppi) was saying, ‘I know there are big problems out there — I have the wherewithal to solve those. Let’s find out what they are and we’ll build solutions for them,’ ” Haley said.

So it didn’t take long for the three Compunetics founders to sniff out a problem to solve. And they aimed high.

Six months in, Compunetics had its potential first client: The U.S. Navy.

“I saw an interesting request for proposal. And I say, ‘We can do that,’ ” he said. Coraluppi, desperate for a contract for his young company, bid the project unusually low, only asking enough for the price of materials. Almost in a call-your-bluff sort of way, the Navy sent representatives to visit the company’s humble headquarters — but not before Coraluppi bought some folding chairs for his guests. He also called upon a lawyer friend whom he said he needed merely as a “warm body.”

Apparently, the meeting went well.

Compunetics was hired for the project, which was part of the Navy’s anti-submarine campaign during the Cold War. Compunetics produced equipment for bases in Jacksonville, Fla., Guam and others.

Eventually, the Navy tapped Compunetics again to develop the electronics used to better detect enemy submarines. That program spanned decades.

‘Competing with Goliath’

It was this proven track record of working well with governmental agencies that thrust Coraluppi’s company into space — with NASA. But the space agency didn’t just hand them a contract.

Coming out of a dark economic period in the 1970s that nearly swallowed his company, Coraluppi invented an algorithm. This algorithm — a complicated set of mathematical rules governed by a computer chip — allowed thousands of callers to join in on one telephone call. It was a groundbreaking advancement in digital technology. In 1984, he filed an application for the invention to be patented.

Meanwhile, NASA needed a more efficient way to communicate with the many teams of people involved with shuttle launches in a single conference call at the same time. By the 1980s, the analog NASA Communications (NASCOM) system was around 30 years old. It was time for an upgrade; NASA put out a call for proposals. Coraluppi knew his invention fit the bill. But Compunetics wasn’t the only company with an appetite for working with NASA. AT&T held similar ambitions, and soon the two found themselves competing for a multimillion-dollar contract that would supply one of the world’s leading space exploration agencies with its communication systems.

NASA eventually chose Compunetics. It was a modern-day story of David defeating Goliath, said Jerry Pompa, Compunetix’s senior vice president.

He summed up his boss’s attitude at the time: “Sure AT&T is gigantic. Their name alone sets them apart. But one-on-one, they’re no better than us. We’re just as good as they are. Why shouldn’t we win?”

Pompa’s position at the company is a direct result of the NASA contract. Coraluppi hired him and many others after Compunetics won the bid against AT&T.

“He’s not intimidated by competing with Goliath,” Pompa said of his boss.

What set Compunetics apart was Coraluppi’s seminal “Compunetics Switching Network” invention. It made it possible for literally thousands of people — in this case engineers, technicians and astronauts — to join in on one call. It was all done digitally and automatically by a computer chip.

NASA launched Curiosity, a rover destined for Mars, on Nov. 26, 2011 from the Air Force Station in Cape Canaveral, Fla. using Compunetix teleconferencing technology. The audio from the video is the technology at work, as teams of people run down all the required checks moments before lift off.

Before the invention, getting multiple people on the same NASA call was possible, but cumbersome. It was a manual duty done by up to 50 trained technicians, according to a Technology.org article written about the system.

With the invention, NASA no longer needed to be preoccupied with the mechanics behind communicating with the people dispersed through a network of 18 ground stations and three ships in different oceans. Those engineers, technicians and astronauts could communicate freely about important details germane to a space launch: monitoring a spacecraft’s fuel levels, watching the weather at a landing site, updating the astronauts’ realtime biometric readings.

His invention made it possible for all those people to instantly connect.

In 1987, NASA awarded Compunetics a $4 million contract to install the conferencing technology for the Goddard Space Flight Center. And earlier that same year, the invention became the first of five USPTO patents awarded to Coraluppi and the company.

By 1992, Compunetics technology had replaced all of NASCOM’s technology and it was used for more than two decades. Eventually, the Federal Aviation Administration awarded them a $4.5 million contract to use the technology, which served as the basis for founding Compunetix, a company that today manufactures electronic products.

Coraluppi then earned another USPTO patent to reproduce the technology for commercial purposes, thus making way for his third company, Chorus Call, a conference service provider.

Since then, tech companies around the world have used Coraluppi’s invention to spawn their versions of it: Zoom, Microsoft Teams, FaceTime, SnapChat, Whats App, etc., etc.

“He was the first one to do it,” said Monica Coraluppi. “The company provided the first digital teleconferencing solution in the world.” Monica, 54, is one of Coraluppi’s daughters. She works at Chorus Call as its director of special projects.

Today, the company’s digital teleconference and videoconference technology is highly used and sought after. Some of the companies’ clients who use the commercial version of the conferencing technology today include Verizon, First Energy, Subway and ESPN. There are also several governmental clients: the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the Department of Justice and the Department of State, to name a few.

The headquarters for Compunetics, including its two spin-off companies — Compunetix and Chorus Call — remains in Monroeville. Compunetix and Chorus Call are in a six-floor office building nestled in some woods just off Mosside Boulevard, down the road from Forbes Hospital. Compunetics is located in a nondescript industrial park building about two miles north on Seco Road.

The photograph and the letter

Giorgio and Luisa Coraluppi’s time in Pittsburgh was only supposed to last a couple years before moving back to Italy. Fifty-two years later, sitting behind his wooden desk in Monroeville, he chuckled at that wistful goal as he peered through his window at the naked mid-March trees. He took a deep breath. It was almost as if the exhale said, “It’s been wonderful.”

At this point, Coraluppi’s success as a business owner has earned him regional, state and national recognition. The debts taken on to start Compunetics without a business plan have long ago been paid. (The company as a whole expects around $100 million in 2019 revenues.) His name is printed on five U.S. patents. He employs hundreds of people, here and in other parts of the world. Those people have given him a loving nickname.

But then another memory floated up into Dr. C’s mind. It was a memory that led the 86-year-old out of his chair.

He walked, without the help of his walker, to a room across the hall from his office. About a minute later, he came back with a wide smile on his face. In his hands he held a framed, underwhelming picture of a machine in a dark room. “This, for me, is more memorable.”

In 1988, he got a call from IBM, a company Dr. C’s had worked with before — but not like this. Their engineers were encountering an issue while building their “RP3X 64-Way Parallel Processor Prototype System.” The supercomputer was designed to process a billion instructions every second, but it wasn’t working. Would Coraluppi come to help them?

Intrigued by the prospect of helping IBM build a supercomputer, which he called a “major, major development” in computing technology, he agreed.

He quickly learned, however, management at IBM had run out of patience and money for the project, which had been fruitless for years prior. Dr. C remembered some of project’s leads had said this issue they were encountering was going to cost them too much money to fix. One of the managers even became hostile by telling him “don’t expect too much money on the table for you.”

“I got upset. I never announced a digit. I didn’t talk about money. I said, ‘Let’s not talk about money right now … forget the money. I’m willing to do this for nothing. Let’s look at the problem and let’s fix the problem,’ ” he said.

And so the arrangement meant leaving his company behind while he and two colleagues worked to fix the problem — for free.

After two months, Dr. C and his engineers had solved the supercomputer’s problem.

His success led IBM’s then-director of strategic development, Alan E. Baratz, to send a framed photograph of the supercomputer with a personal message typed on the back: “Your efforts were critical to the successful completion of the RP3X 64-Way Parallel Processor Prototype System.”

That happened 31 years ago.

“And I still keep it,” Dr. C said about the photograph and the letter. He said only two physical copies of that photo exist. The other is with Baratz.

IBM’s computer went on to achieve “significant advances in the research of particle physics,” according to Compunetics — which, led by Dr. C, built a circuit board for the computer. The favor did not go uncompensated. A relationship sparked. Some years later, IBM awarded his company a lucrative contract. That project entailed building and installing hardware for IBM’s Deep Blue computer. The machine became the first to defeat reigning World Chess Champion Garry Kasparov in 1997 — a match that Dr. C witnessed in person as one of the only non-IBM employees in the room.

The Deep Blue computer is now referred to as the Watson, which beat “Jeopardy!” champions in 2011. Since 2013, it has helped doctors diagnose and treat lung cancer in a New York City hospital.

The induction

The man they call Dr. C also responds to “papá,” the Italian word for dad.

Giorgio and Luisa raised four children who are bilingual, having spoken Italian in the home. When Monica Coraluppi was in high school, she remembers her papá was always knowledgable of the subjects she was learning about.

“He’s an avid reader. He reads constantly — all kinds of books. So whatever I was studying in high school, he knew what I was talking about. As I was going through school, I could go to him for help. Because he’s very good at taking a complex message and breaking it into parts so that I could understand,” she said.

Monica is one of three Coraluppi children who still live in Pittsburgh. She said her father has always inspired her, which is partly why she has stayed.

And so, like many of his colleagues, she is proud her papá will be inducted into the Space Technology Hall of Fame at the 36th annual Space Symposium in Colorado Springs for inventing the digital teleconference technology. The honor would have happened in early April, but like most everything else, the symposium was rescheduled for late October because of the covid-19 pandemic.

The hall of fame is designated for companies and inventors whose creations originally designed for use in space have transformed life on earth. For example, the man behind the Bowflex exercise machine that changed weight training originally invented a device astronauts could use to stay strong while in space. That inventor, Paul Francis, was inducted into the Space Technology Hall of Fame in 2019.

This year, there are three other individuals like Dr. C being inducted for their inventions. The Compunetics founder is the only man still living, which raises the question: When, if ever, will the man retire? Hasn’t he earned it?

It’s a question one of Coraluppi’s longtime friends, Robert Kampmeinert, has discussed with him. Kampmeinert, 76, of Fox Chapel, retired a decade ago from a career in investment banking.

“We’ve had heart-to-heart talks. Everyone’s different. Some people aren’t …” Kampmeinert trailed off. He resumed: “This has been his life, these companies. And they remain such.” In 2012, the friend joined the company’s board of directors. It’s a topic that comes up during board discussions, but the group has never asked Coraluppi to retire or otherwise step down from leadership.

Besides, Kampmeinert said, “he’s as sharp as ever mentally.”

The next frontier

Pinpointing a reason behind Dr. C’s uninterest in retirement might seem complicated, but it’s simple.

He’s not done.

“I don’t think he will officially, under his own direction, give in to this idea of retirement,” said Mike Hockenberry, Compunetix’s federal systems division manager and the company’s vice president. “If he can keep going, he wants to keep going.”

Hockenberry tells it like this: “I would joke that if on any given Sunday, you drive past Compunetix, you’re most likely to find his car there.”

And Hockenberry imagines that his boss is sitting at his desk, working on cracking a math problem he started tackling decades ago.

It’s a math problem that was first posed by Carl Friedrich Gauss, the German genius regarded as the Prince of Mathematicians, in his 1801 book “Disquisitions Arithmeticae.”

“The dignity of the science itself seems to require that every possible means be explored for the solution of a problem so elegant and so celebrated,” Gauss wrote of the mathematical conundrum.

In plain language, this is the problem: If you were to deconstruct a 300-digit number, how would you put it back together? What numbers are used to get to the final product of a gargantuan number like that? In math-speak, the problem has been boiled down to this: What is the factorization of large whole numbers?

Some say it would take thousands of years to figure out all the ways a number that large can be factored. Forget about doing it by hand. It’s a problem for the ages, one that has only recently become possible to solve through advances in supercomputing. That’s where Dr. C’s intrigue comes in.

As of May 2019, the inventor claims to have found the answer. He received a U.S. patent that legitimizes his theory and method for solving the problem. The next hurdle is applying it, finding a way to compute those 200- and 300-digit numbers quickly. If that can be done, the implications would be immeasurable and the applications innumerable for the world of data encryption, Dr. C said.

For example, in his patent, Dr. C said one application could be to intercept encrypted communication between terrorist organizations quicker and to use that information to automatically notify law enforcement agencies of a potential threat — before it ever happens.

“My conviction is that the solution that what I have presented is the primary avenue for the resolution,” Coraluppi said, adding he plans to use a Carnegie Mellon University supercomputer to do it. He’s confident his method can be implemented successfully within a year.

For Dr. C, finding the answers to the Gauss problem began as an intellectual pursuit — almost a hobby. Now, though, it’s a possible new frontier for his businesses, which employs people he cares for and loves.

This is just one of several reasons Monica Coraluppi continues to be inspired by her papá. She also resents the question of whether he, with all the potential behind his mathematical pursuit, should retire.

“The question leads to a judgment of him because of his age. We should not be judgemental based on age, religion, color — whatever,” Monica Coraluppi said. “There’s this paradigm that people of a certain age should act in a certain way.”

Following a long pause, one reminiscent of the deliberate pauses taken by her father, she brought up Frank Lloyd Wright, who died at 91 in 1959. She said some of the famous architect’s greatest work was achieved later in life, post-retirement — when most people think a person should be finished.

Indeed, Wright died six months prior to the opening of the Guggenheim Museum in New York City, a project he began 16 years before his death. The building is revered as the best work of one of the country’s most beloved architects.

She switched back to her papá.

“This man’s not done. And the best is yet to come.”

And so, maybe the appropriate question to ask is not whether Dr. C should retire.

Should we?