In May 1938, Henry Ellenbogen, a prominent Pittsburgher, received a letter from a Jewish garment cutter in New York City’s Bronx borough. The man needed Ellenbogen’s help cutting through government red tape so he could bring his brother and mother to America from their native Austria.

“I hope to God that it will be possible for you to grant our request,” the garment cutter, Fred Goodman, wrote 16 months before the Nazis invaded Poland, triggering the start of World War II. “We beg you most sincerely to spare no efforts to facilitate our receiving permission for this step.”

Ellenbogen was intimately familiar with these types of pleas, which routinely arrived in his mailbox from around the world.

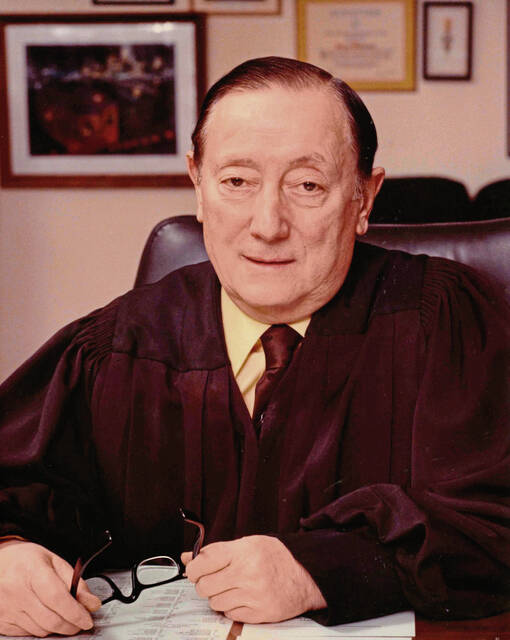

By day, he served as an Allegheny County Common Pleas judge who had just ended his third term in Congress. But Ellenbogen’s hours also were occupied by another pressing responsibility: writing letters and telegrams to Jews struggling to flee Nazi persecution.

An Austrian-born Jewish lawyer and politician whose second-act career as a judge spanned four decades, the Pittsburgher helped save hundreds of Jews by helping them navigate a cumbersome, sometimes-confusing bureaucracy — one that he understood all too well as both a public servant and an immigrant himself.

As one of about 10 Jewish leaders in Congress in the 1930s, his legacy also remains intertwined with the plight of Jews before and during World War II.

“I received your letter and wish to thank you for the kind interest you are taking in my brother-in-law, Adolf,” Leopold Mehler, a doctor on New York City’s Park Avenue, wrote to Ellenbogen on April 22, 1938, less than a month before Goodman’s letter arrived in Pittsburgh. “Adolf asked me to write you that a letter of recommendation from you to the American Consul would be of great help.”

“Mr. Kehring is the manager of this company,” Richard Lehr wrote to Ellenbogen from London on Jan. 26, 1940. “As long as he does not ask for any money from you, I should be obliged if you would be helpful to him.”

These letters are among 574 pieces of correspondence between 1934 and 1943 documenting Ellenbogen’s efforts to help Jews escape the Holocaust that Pittsburgh’s Sen. John Heinz History Center’s Rauh Jewish History Program & Archives posted online in May in a new digital archive.

Ellenbogen’s work before the war has been largely unheralded, though Pittsburgh-based archivists hope the digitization effort makes Ellenbogen’s low-profile efforts more visible — especially to researchers and biographers who continue to write the history of Jewish migration before and during World War II.

“In that (Goodman) letter, you see how international events shape personal lives,” said Eric Lidji, the Rauh archive’s director. “You get a sense of these larger things, the way international events throw people around, like waves in the ocean.

“You get to see how difficult and complicated it was … to help people get out of Europe.”

Writing history

Digitizing part of the large Ellenbogen archives, which the history center received in 2000, is particularly important as the work of historians shifts, Lidji said.

Previously, those writing about Ellenbogen’s role in World War II history would have needed to visit Pittsburgh while poring over the archives at the Strip District-based history center. Now that some of Ellenbogen’s papers are available online, historians have direct, free access to his role in Jewish migration before and during the war. By extension, archivists say, it will be easier to write him into history books.

Judi Ellenbogen, the congressman’s daughter, grew up not knowing about the work her father did to help people immigrate to the U.S.

“I knew very little about these letters, about my father,” Judi Ellenbogen, 84, said recently as she sat in her Shadyside apartment. “I knew my father had come to the United States and I knew from where, but he never told me why he came. It was never a topic.”

She discovered her father’s papers after he died on July 4, 1985.

“When I read these letters, they were overwhelming — that’s all I could say,” Ellenbogen said. “And I thought, ‘Something should be known about this.’ ”

Vienna to Pittsburgh

Born in Vienna in 1900, Ellenbogen immigrated to Pittsburgh in 1921, according to family members and his archives. He worked at Kaufmann’s department store in Downtown Pittsburgh and attended Duquesne University’s law school at night.

Ellenbogen went on to practice law in Pittsburgh in the early days of the Great Depression and was “greatly moved by the plight of the impoverished, the unemployed and the dispossessed,” historian Kurt F. Stone wrote in his 2011 book, “The Jews of Capitol Hill.”

Mentored by a politically active Pittsburgh priest, the Rev. James R. Cox, Ellenbogen marched in Washington, D.C., in 1932 to promote investment in public works projects and unemployment relief. Ellenbogen and Cox later met with then-President Herbert Hoover.

“Hoover turned a deaf ear on their proposal” for unemployment relief, Stone wrote. “Stunned by what he saw as Hoover’s blindness — or insensitivity — Ellenbogen decided that he must do something to aid the ‘forgotten man.’ ”

That same year, Pittsburghers elected Ellenbogen to represent their city in the U.S. House of Representatives.

In the Capitol, Ellenbogen charted “a progressive, pro-New Deal course,” Stone wrote. One of the first politicians to back Social Security legislation for the elderly and unemployment insurance, Ellenbogen helped draft the Wagner-Ellenbogen bill to create a federal authority whose proposed $850 million budget would have built low-cost housing and helped eliminate slums. A revised version was signed into law in 1937.

Ellenbogen served in Congress for six years. He was reelected in 1934 — with 98.7% of the vote — and in 1936.

Treading carefully

In Congress, Ellenbogen was typical of Jewish politicians of the era, according to one Pittsburgh-based historian. Like many, Ellenbogen didn’t speak publicly about how Jews weathered the march to war in Europe.

“Ellenbogen was not unique in not speaking up,” said Barbara Burstin, a history professor at the University of Pittsburgh who has written several books about the Holocaust and the history of Jews in Pittsburgh. “If you fault Ellenbogen, you have to fault all of the Jews in (President Franklin D.) Roosevelt’s administration.”

In May 1933, Ellenbogen wrote a memo to Roosevelt, asking him “to try to bring about the just and equal treatment of the Jewish people in Germany,” Burstin said.

His activism ended there.

“He was a foreign Jew. He was born in Vienna,” Burstin said. “If he spoke up, he really could have been labeled disloyal to the country and he would have faced vitriol from the right.”

Ellenbogen left Washington, D.C., and started his next chapter in Pittsburgh, where he ran for a judge’s seat on the Allegheny County Court of Common Pleas. He served the local courts from 1938 until an age-mandated retirement in 1977.

The archived letters stretch from his years in Congress to his time as a Pittsburgh judge.

“This is a local hero,” said Catelyn Cocuzzi, Rauh’s project archivist. “This is someone who helped hundreds, if not thousands, of people to flee the Nazis in Europe.”

Desperation on paper

The correspondence, often dry and driven by bureaucratic processes, involved Ellenbogen connecting government officials with Jews looking to flee the Third Reich. For Ellenbogen, it was a part-time job. He had no computer, no secretary to whom he could dictate letters.

“What this shows is a person very knowledgeable of the system, explaining how it works to help people,” Lidji said. “This story of human migration is a perpetual issue — it’s always in the news. But when you read these letters, you really get a sense of the human element of this issue.”

If Ellenbogen harbored opinions or political views of the Nazi regime’s rise, he rarely hinted at them in the letters he sent to Jews overseas seeking his help. His correspondence revolves around largely administrative details — a kind of code all its own.

“I have, in the meantime, received a letter from Mr. John H. Bruins, American Consul at Prague, to the effect that his office has no record of a visa application filed by you,” Ellenbogen wrote to Emanuel Ellenbogen, who was not related to him, in Prague on April 12, 1939. “I am enclosing the Consul’s letter and am also enclosing a letter which you can present to him and discuss your case with him.”

Cocuzzi said she spent eight hours a week, every week for six months, scanning two boxes of Ellenbogen’s letters. A batch of documents from the next Ellenbogen boxes will be posted online before the end of the year.

The work merely scraped the surface. The entire archive fills 44 boxes, or about 24 linear feet.

The Ellenbogen archive is large in terms of papers and files from an individual, Lidji said. By comparison, the largest Rauh collection — records from the Jewish Federation of Greater Pittsburgh — runs 221 linear feet, nearly 10 times the size of the Ellenbogen archives.

Filing and scanning the letters was an emotional task. Cocuzzi said she couldn’t help but dive into stories like Goodman’s when scanning the documents.

“There were so many stories — and these are only the ones we have,” Cocuzzi said. “It’s entirely possible there were more than those that went into his files.

“Every single one of these letters is beyond interesting,” she added. “You can hear the pain in these letters, the pain of these people trying to get out of Europe.”

Educators also might find the digitized archives are valuable in a different way when teaching about the Holocaust. There’s a humanity to those writing Ellenbogen that sometimes is lost in history books, Lidji said.

“There were times (letter writers) were encouraged and times they were frustrated,” he said. “It’s important to read through that and see that process.”

Unfinished business

Judi Ellenbogen grew up in Pittsburgh and moved to Florida in adulthood. She boomeranged back — this time to an apartment on Fifth Avenue — about two years ago for some unfinished business: getting her father into history books for his behind-the-scenes efforts to help his people.

In 2000, when the Rauh archives received the Ellenbogen letters, the internet was still in its infancy, Lidji said. More than two decades later, its explosive growth as a research tool finally has caught up with Judi Ellenbogen’s ambitions.

“One of the reasons I wanted to come back is that I thought there was something unfinished,” she said. “And I wanted to finish it.”