Half a century after the murders of his parents and sister, the emotional wounds are still raw for Joseph A. “Chip” Yablonski, the last surviving child of Jock Yablonski.

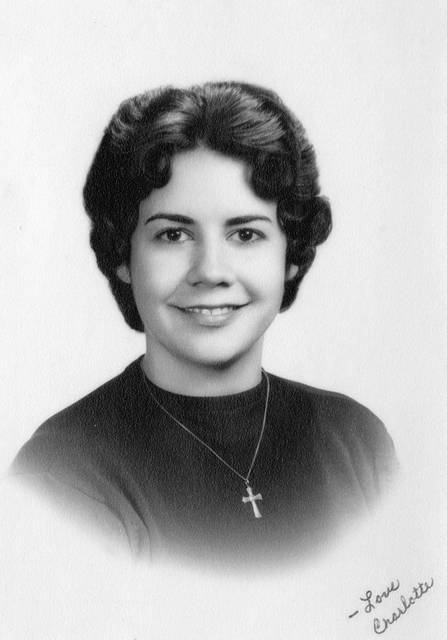

Losing his family was traumatic enough. But as he sat at the dining room table of his Bethesda, Md., home this month, tears raced down his cheeks as he thought of his sister, Charlotte. At 25, she was the baby of the family, and Joseph Albert “Jock” and Margaret Yablonski’s only daughter.

“What a wonderful person,” said Chip Yablonski. “She would have made a great mother and a fine wife. And I miss her.”

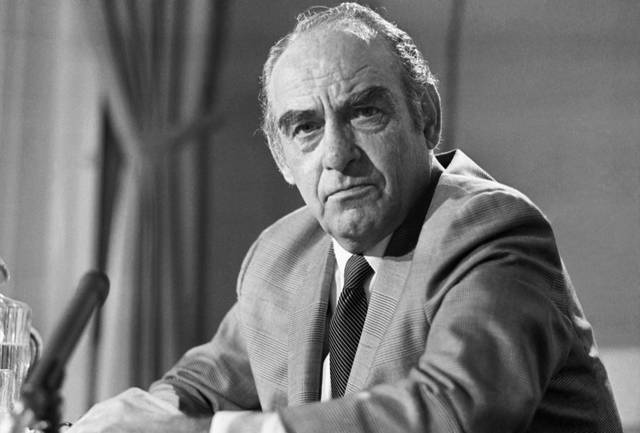

On Dec. 31, 1969, three weeks after Jock Yablonski lost an election for the presidency of the United Mine Workers of America to incumbent W.A. “Tony” Boyle, three assassins hired by Boyle broke into Yablonski’s farmhouse near Clarksville, Pa. They fatally shot him, his wife and Charlotte Yablonski.

The Cleveland, Ohio-based gunmen, Paul Gilly, Aubran “Buddy” Martin and Claude Vealey, were described as “clowns” by Cleveland police Commissioner Clifford Bruce. They did a poor job of covering their tracks and were soon captured.

But many, including some UMWA members, refused to believe the union leadership had anything to do with the Yablonski murders. Nearly four years passed before Boyle was arrested for the killings.

What has been called the last political assassination of the turbulent 1960s devastated a family and shocked a nation. The murders led to major reforms of a union rife with corruption which, to that point, had been woefully inadequate when it came to protecting its members.

It also emboldened Yablonski’s sons, Ken, the oldest, and Chip, both attorneys, to join forces with others to create Miners for Democracy and to push for an FBI investigation of the murders which they believed from the beginning Boyle had plotted.

Life on the farm

The last time Chip Yablonski, 78, saw the three-story fieldstone farmhouse he grew up in, he said it looked decrepit.

The house has quite a history, dating back to 1778 when it was built by Henry Enoch, a lieutenant colonel in the Revolutionary War. It overlooks Tenmile Creek, which flows into the Monongahela River.

Mike Packrall and his wife, Kathy, now own the home and are restoring it. The house looks foreboding from the road as it sits empty at 5 Polly Ave.

Yablonski remembers when the house and the land around it teemed with life.

“My dad loved life,” Chip said. “He was a man’s man. He loved cigars. He loved good scotch.

“I have such memories of growing up and learning how to throw a hay bale and being up on the truck and having my brother and his friends trying to knock me off the truck by throwing bales of hay at me,” he said with a laugh.

According to Chip, his dad bought the farm to “keep his kids out of the pool halls.”

He let the kids run the farm. They brought in the hay, plowed the land, planted oats and barley, raised cattle and even helped Jock Yablonski birthing calves.

“He taught us responsibility,” Chip Yablonski said. “I hated the responsibility at the time, but I look back on those days with great fondness.”

Wild child

Jock Yablonski was concerned about his children inheriting the wild streak he lived through before he met and married Margaret and settled down to raise a family.

He was born Joseph Albert Yablonski, was baptized in Pittsburgh in 1910 and came of age in the roaring ’20s. In 1932, he spent six months in the Allegheny County Jail for what Chip described as “breaking into a slot machine or something in some Moose lodge.” His criminal record would be used against him in subsequent campaigns, including his bid for the UMWA presidency some 3½ decades later.

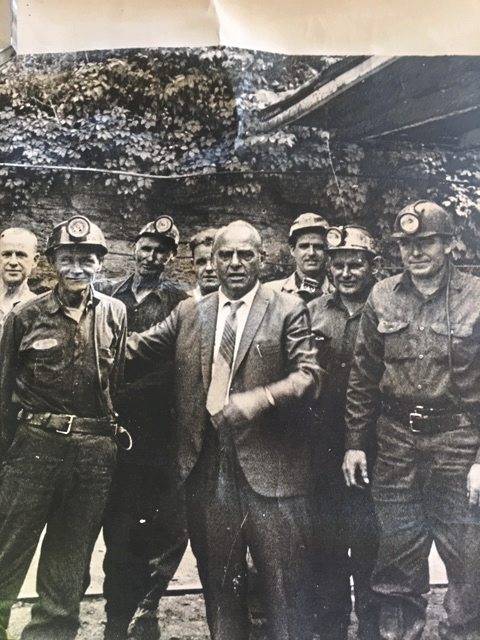

Jock Yablonski was destined to become a reformer and run for leadership positions in the union. Coal mining was in his blood. His father was a coal miner and died in a mining accident in the early 1930s, when a piece of slate gouged him in the stomach area. He developed an infection and died of sepsis a week later.

He dropped out of school in the eighth grade to work in the mines and help support his family. There, he witnessed firsthand the hazards associated with the profession, including the effects of coal workers’ pneumococcus or black lung disease caused by long-term exposure to coal dust.

“This is the world that my father grew up in,” Chip Yablonski said. “He had grown up in an industry where mine explosions occurred all the time, and they were just too damn common. He came to believe that that was just insane.”

Jock Yablonski’s father’s tragic death led him to become active in the UMWA, and he was first elected to union office in 1934.

Once he married Margaret, Jock Yablonski followed a path that would lead to bigger and better things. But being a leader involved more than being a confident guy with a magnetic personality, qualities that Jock Yablonski possessed. He was intelligent but didn’t have even a high school education. That’s where his wife came in.

Margaret Yablonski was a prolific writer who was offered a contract as a screenwriter. But accepting the opportunity would have meant moving away from Pennsylvania, and her husband didn’t want to do that.

She had written stage plays, including one called “Shorty” about a coal miner that was produced at the Pittsburgh Playhouse in 1948 (Jock Yablonski was credited as a co-author). She also wrote short stories and magazine articles for publications such as Esquire.

“Esquire did not accept women writers, so she used my dad’s name,” Chip Yablonski said. “She was published under the name Joseph Yablonski. I’m certain those things were not published without him having read whatever she was submitting.”

Margaret Yablonski was a woman of culture, a voracious reader who hung poetry selections in the bathroom. Her husband was amenable to her lessons.

“We had a lot of literature in our house. We (kids) were force-fed it, but he was attracted to it,” Chip Yablonski said.

Charlotte had inherited her mother’s dramatic flair and was described as the family comedienne.

“She loved the theater; she acted at Little Lake Theatre (in Canonsburg). She was a drama queen from a very early age and flaunted it, and all of us loved her for it,” Chip Yablonski said.

“More than Ken or me, she was really into doing charitable stuff.”

After getting her master’s degree from West Virginia University in 1967, Charlotte took a job at Mercy Hospital in Pittsburgh working with alcoholics, drug addicts and people at risk of committing suicide. She became the director of the Office of Economic Opportunity antipoverty program in Monongalia County in West Virginia before leaving to work on her father’s campaign.

“(Margaret and Charlotte) were creative, good people who made my dad what he was,” Chip Yablonski said.

Rising in the ranks

By the 1950s, Jock Yablonski had become a sought-after guest lecturer, appearing regularly at Carnegie Tech’s School of Management to give speeches about labor’s goals and philosophy. He was becoming a force in Pennsylvania politics and, beginning in 1952, participated every four years as a delegate to the Democratic National Convention.

“He became a transformative figure,” said labor historian and author Charles McCollester, a retired professor of industrial and labor relations at Indiana University of Pennsylvania. “He was a tough, old-guard guy who had a heart and had a broader mind. He was a serious reader and a working-class intellectual.”

And he got things done. In 1954, he created Centerville Clinics Inc., which provided health care for miners and their families who could not otherwise afford it. He also served as chairman of the board of the new Brownsville General Hospital.

By 1958, Yablonski had risen through the union ranks to become president of UMWA District 5 in Southwestern Pennsylvania. He was elected to a position as a representative to the international executive board. Two years later, labor’s legendary UMWA president, John L. Lewis, retired. His successor, Thomas Kennedy, died in 1963.

Still wielding considerable influence in retirement, Lewis decided Tony Boyle would be the next UMWA president.

“When Lewis was president, there were lots of things that could have been done in the area of mine safety and other benefits that were not achieved, and Boyle stepped into Lewis’ shoes and did essentially the same thing,” Chip Yablonski said.

Boyle was known as a bully who maintained close ties with the mine owners. Former West Virginia congressman Ken Hechler said Boyle made “sweetheart deals” with some coal companies and ignored conditions that were unsafe for miners.

Boyle and Jock Yablonski clashed almost immediately.

A dangerous decision

Dissent was not tolerated in the UMWA, not by Lewis and certainly not by Boyle when he became president.

“Boyle had a mean streak, and it manifested itself long before he ordered the murder of my dad,” Chip Yablonski said.

In 1964, Boyle accused Jock Yablonski of not helping his campaign for reelection to the presidency, despite the fact that Boyle won District 5 by a 4-to-1 margin. Boyle would eventually force Jock Yablonski to resign as District 5 president.

Boyle charged him with insubordination after Yablonski worked with the Pennsylvania Legislature to pass a bill compensating miners suffering from black lung. Certainly, the industry didn’t want it, and Boyle said the time wasn’t right for it. But Yablonski ignored him, and Gov. William Scranton ended up signing it into law.

Boyle was irritated. He perceived Yablonski as a threat who was trying to undercut him with the membership.

Subsequent events — such as the November 1968 Consol No. 9 coal mine explosion north of Farmington, W.Va., that killed 78 miners — pushed Yablonski to challenge Boyle for the UMWA presidency.

“When the mine exploded, Boyle showed up on the scene and said, ‘Consol was a really good operator and as long as we mine coal, men are going to be injured and die.’ And my dad just couldn’t take that. He knew there was something that could be done to prevent it. That and other events pushed him to become a candidate,” Chip Yablonski said.

Jock Yablonski declared his candidacy in May 1969. By June, Boyle decided it was necessary to kill him, according to subsequent trial testimony.

“When (Yablonski) called for rebellion, it really touched a chord among the mine workers who had been asleep for quite a while,” McCollester said. “There was a whole new generation coming into the mine workers in the late ’60s, younger, working-class people and radicals and also women came into the mines. There weren’t a lot of them, but they tended to be lefty, ’60s people.”

In an effort to keep a close eye on Jock Yablonski, Boyle assigned him to a post in Washington, D.C. By July, Jock Yablonski had moved in with Chip and his wife, Shirley, in their Bethesda home. Early one morning, two strange men showed up at their door while Jock Yablonski was taking a shower.

“My wife answered the door and these two grizzly-looking guys said, ‘We’re here to see Jock Yablonski; we’re looking for a job,’ ” Chip Yablonski said. “My wife had the good sense to say, ‘He’s not here; he’s off campaigning.’ She came and got me, and I saw them.”

One of the men at the door was Claude Vealey. He went away, but he was not done tracking Jock Yablonski.