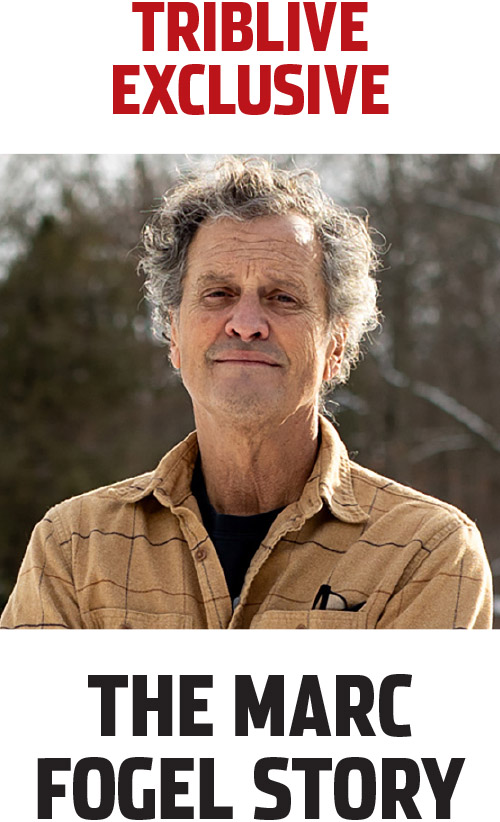

Story by PAULA REED WARD

TribLive

Feb. 9, 2026

On Aug. 13, 2021, Marc and Jane Fogel pulled away from their white colonial-style home in Oakmont to drive to New York City.

There, they boarded a plane to Moscow to begin their final year teaching at the Anglo-American School, an elite institution built for the children of western diplomats.

But when the couple landed, Russian authorities arrested Marc Fogel, seizing from him less than an ounce of marijuana he had been prescribed in Pittsburgh to alleviate severe back pain. A judge convicted Fogel of drug smuggling and sentenced him to prison.

So began an excruciating ordeal that kept Fogel in Russian custody for 1,277 days.

On Feb. 11, President Donald Trump’s administration secured Fogel’s release and brought him home.

This is Marc Fogel’s story.

On a Saturday morning in September 2022, Marc Fogel, carrying two bags of belongings, boarded a prison train to begin an arduous 200-mile journey north from Moscow. His destination: the city of Rybinsk.

Originally populated by fishermen hundreds of years ago, Rybinsk became a center of steamship construction in the 18th century as well as a manufacturing hub for rope, bricks and wheat.

Picturesque and quaint, the city of roughly 200,000 people sat along the Volga River, Europe’s longest waterway. It retained an Old World charm.

But Marc wouldn’t enjoy the sights. He was heading for Rybinsk’s penal colony.

Convicted of drug possession and smuggling on a large scale for bringing medical marijuana into Russia, Marc had been ordered to serve a 14-year sentence in what the judge called “a correctional colony of strict regime.”

Driving straight from Moscow to Rybinsk would take about five hours. But on the overcrowded prison train — known as a stolypin, a vestige of the Soviet gulag system — it would take Marc more than six weeks of zigzagging around the country before he reached the hard labor camp.

═══════

The series

Chapter One: From Darkness to Light: Marc Fogel’s journey to freedom

Coming Tuesday: Chapter Four: Freedom

Coming Wednesday: Chapter Five: Home

═══════

During the journey, called an etap in Russian, Marc was held incommunicado, forbidden from contacting anyone. Neither his family nor his lawyers knew where he was.

Prisoners on the train were kept clueless about their whereabouts and route, as well. The stolypin cars were attached to ordinary passenger trains and took a circuitous path, stopping at various prisons.

At first, Marc believed he was heading east toward Corrective Colony No. 2 in Mordovia, where most American prisoners were held — including WNBA basketball star Brittney Griner.

But then his train turned around.

Conditions on board were cramped. The stolypins measure about 38 square feet but carry as many as a dozen prisoners.

With four bunks on each wall, prisoners have only about 6 inches of space above them. The cars lack windows and are often too confined to allow a person to stand.

Trips often began before dawn and ended late in the evening.

At each stop, prisoners were unloaded and taken by vans to a local detention facility, known as a SIZO, for a temporary stay. Sometimes it would last a night, other times weeks or even months.

The prisons were damp, chilly and foul.

Late at night on Marc’s fourth day aboard, the stolypin stopped at the remote Pre-trial Detention Facility No. 3 for the Nizhny Novgorod Region about 300 miles east of Moscow.

Built in the 1800s, the prison looked straight out of a horror movie. Marc remained there, in solitary confinement, for 10 days.

At one point during his transport, Marc gained access to a cellphone — he doesn’t remember how — and for the first time in more than a year called his wife, Jane, on FaceTime.

It was seven hours earlier in Oakmont, where Jane was taking a walk with one of Marc’s sisters, Anne.

Anne was elated but also dumbfounded to see her brother’s face pop up on the screen.

“It was incredible to hear his voice,” Anne said, “to see him. But you’re thinking, ‘Are you crazy? Are you out of your mind? You’re taking this huge risk.’ It was worth it to him. It was terrifying.”

In late October, Marc finally arrived at Rybinsk, a large post-Stalinist-era facility built in 1953. It could hold up to 1,200 men.

Inmates there made coats in a sewing factory, and Marc said corrupt guards ran the prison system.

He was now a prisoner of Penal Colony No. 2.

Although it had been months since he learned his sentence, Marc still was distraught when he arrived.

“There was no coming out of 14 years. People my age — nobody does 14 years,” he said. “The sentence was so grotesque that it was viewed by me as a death sentence.”

Marc never lost that feeling. It was made worse when he got to Rybinsk by everyone repeatedly asking: “What’s your srok?” which translated to: How many years are you here?

Marc felt like a zoo animal — the American on display for all to see. Eventually, he pretended he didn’t understand the question.

For the first 15 months of his detention, Marc did not have a single phone call with his family until the FaceTime from the stolypin. That changed in Rybinsk.

Marc learned that prison officials wanted to ensure he was kept safe. He said the guards asked inmates who were in the Russian mafia to keep an eye on him. That meant sometimes getting extra food, feeling that he had some protection, and having access to burner cellphones to call home.

It was an incredible luxury. Prisoners typically had to pay about $300 for 15 minutes of phone time.

Marc said he saw hundreds of burner cellphones stolen from prisoners by the guards, who would then sell them to other inmates.

Marc remembers making his first official call home from a filthy room packed with other prisoners. He dialed Jane, and she called him back. They talked for a few minutes. During their conversations, he worked to keep himself together.

“It took a while not to crack up, but a lot of times I was in a public arena so I had to keep myself in order,” Marc said.

Most of his calls were “very vanilla,” catching up on family matters, Pittsburgh sports and other light topics. Even on the burner phones, Marc said, nobody trusted that Russian officials weren’t listening.

Marc fell into a routine of making at least one call a day around 5 p.m. — morning in America — and rotating among his immediate family.

Mondays were reserved for his mom, Malphine. From 5,000 miles away, she would read aloud the Butler Eagle sports page, something Marc especially looked forward to during Steelers season.

Marc learned he couldn’t count on phone access. At random, the guards would sometimes take the burners away. He might lose communication with his family for weeks.

After Marc lost all of his appeals in the Russian court system, his family and friends in the U.S. were trying to figure out what they could do.

They decided on a media campaign.

In the months after Marc’s arrest, the State Department under President Joe Biden urged the Fogel family to keep a low profile.

It was far different from the high-profile case of the WNBA’s Griner, arrested while entering Russia six months after Marc for carrying vape cartridges with cannabis oil.

The Biden administration believed that promoting Marc’s circumstances in the media could make him a more valuable commodity and prompt the Russians to demand an even higher price for him.

Until his conviction, Marc’s family had followed the government’s advice. But after Marc was sentenced, attorney Sasha Phillips said, they knew they had to switch their strategy.

“We just basically started knocking on every single door, whether that came to PR or congressional outreach or really anything we could do on (Capitol) Hill at that time,” Phillips said. “From that point forward, we just started raising Marc’s profile in every way.”

Across Rybinsk’s 40-acre compound, there were a dozen separate barracks, some holding 40 prisoners, others as many as 100.

Marc primarily lived in Barrack No. 10, a relatively clean, two-story building with a pair of refrigerators and metal bunk beds. It had a reputation as one of the penal colony’s nicer quarters.

Prisoners typically had to pay hundreds of dollars in bribes to stay there.

“You paid money to put paint on the wall,” Marc said. “If they had to fix toilets, you paid for the toilets to be fixed.”

The Fogel family devised a way to get Marc money to use for daily living in the colony. With their help, he landed a better mattress and improved housing.

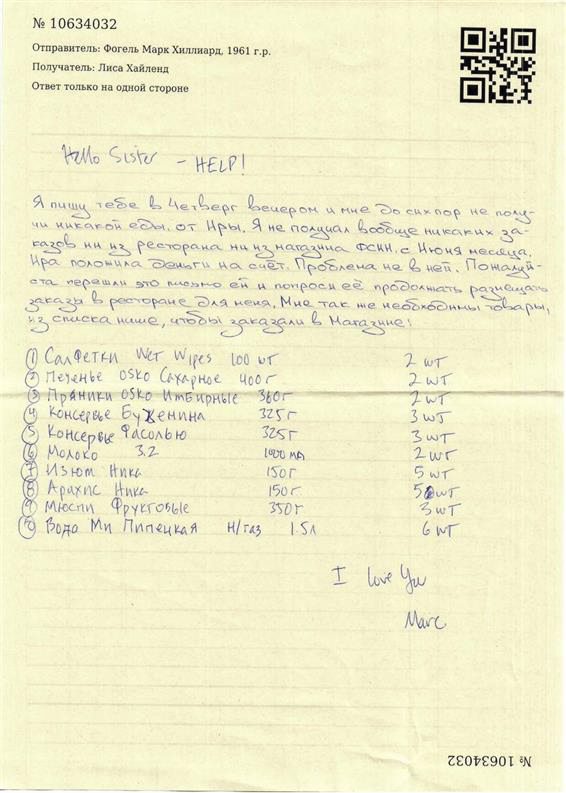

They sent funds to Marc’s friend and translator, Irina Pigman, a Russian who lived part-time in Florida with her American husband. Irina, in turn, would forward the money to a former inmate living in exile near the prison, who bought food and other supplies for Marc.

Some inmates bribed guards to sneak in electric heaters. Others made moonshine.

Prisoners snored, talked and smoked, making it hard to sleep. Worse, prison officials kept the lights on all night after the colony shut down at 10 p.m.

Pain from years of back operations flared up every time Marc clambered between the ground and his top bunk for twice-daily head counts by the guards.

Each morning started with an inspection that Marc characterized as “a bunch of buffoons smoking cigarettes.” It reminded him of a scene from the 1981 comedy “Stripes.”

Life at Rybinsk was unpredictable. During inspections when higher-ranking officials toured the colony, inmates scrambled to hide the barrack’s microwave. Other times, fickle guards would sell the appliance on Russian eBay, forcing the prisoners to scrounge for another.

Although he was held in a labor colony, Marc’s age and health prevented him from having a job.

That meant he spent the majority of his days inside the barracks, walking on the prison property or visiting a small church on the grounds.

He also fell back on the one thing he knew best: teaching.

Marc had taught at international schools around the world for nearly 40 years. His last post, with Jane, was at the Anglo-American School in Moscow.

At Rybinsk, he gave English lessons to fellow prisoners. Planning daily lessons helped kill time. He and his students would meet in the dining room or in a gazebo.

They would pay him in extra hard-boiled eggs and vegetables. His ideal charge for five lessons was three chicken breasts.

Sometimes he received cut carrots, beets or bread. But guards occasionally cracked down on the lessons. It was the meat that got him into trouble.

“Somebody ratted out them and me,” Marc recalled, “and I was told I wasn’t allowed to do that anymore.”

Marc spent time with a group of Cuban prisoners, frequently speaking with them in their native tongue. He had learned Spanish decades earlier while teaching in Mexico, Colombia and Venezuela. He and the Cubans made fun of the guards. It helped him cope.

“That was sort of one escapism,” Marc said. “We would be laughing and talking down on the Russians, where nobody could understand us.

“You could sense the people around us knew we were laughing at them.”

Because of his status as an American protected by the Russian mob, Marc was one of the few prisoners permitted to walk around the colony on his own — though not without sporadic difficulties.

Sometimes guards hassled him.

What are you doing out here? they would say. You’re not allowed to be out here by yourself.

“It was a total setup just to get something on my record,” Marc said. “I had that freedom to do it, but they knew to stop the freedom every once in a while.”

Prisoners at Rybinsk were permitted to shower once a week with hot water, but how long the shower would last was anyone’s guess. Sometimes they would be forced to stay in the dank, disgusting stall — with their towels and clothes — for five minutes; other times it could be three hours.

“Nobody would let you out, and you’re sitting there waiting for somebody,” Marc said. “People are screaming, pounding on the door. Everybody’s smoking. There’s no windows.”

The prisoners who were skilled at working in the sewing factories often made their own clothes and sold additional pieces to fellow prisoners and guards, who occasionally took them home to their families.

One prisoner made Marc a better pair of uniform pants and a nicer hat. But most of the time, he wore the two or three black uniforms trimmed with gray that prison officials gave him.

During Marc Fogel’s 3 1/2 years in Russian custody, he was held in no fewer than a half-dozen corrections facilities. When he was transferred from the detention facility in Moscow to begin serving his sentence at a hard-labor penal colony in Rybinsk, the 200-mile trip took nearly six weeks via train — called a Stolypin, a vestige of the Soviet gulag system.

Having a regimen made life easier, though Marc remained vigilant. One friend he made at Rybinsk would say, “Come on, Marc. It’s not so bad here. You’re lucky.”

Marc knew Rybinsk was much better than other prison colonies, like Mordovia. He was never beaten or tortured. And he had a level of independence that helped keep the daily monotony at bay.

But it wasn’t just the conditions of his confinement that impacted him, or losing his freedom. It was also the constant mind games by the guards, like periodically curtailing his English lessons or questioning his ability to roam across the compound.

Sometimes, prison officials would learn a group of inspectors was coming from regional headquarters. They forced the inmates to spend days preparing. That meant hiding contraband — like the precious stash of English-language books Marc had acquired during his captivity.

The inspectors might stay for a week, closely monitoring the prisoners.

“They were always watching me,” Marc said. “They’re saying all this (stuff) in Russian. I just know they’re mad and angry.”

Marc tried to never react. He knew he needed to maintain a stoic demeanor — “the typical Russian granite face.” Sometimes the guards would be nice to him again the next day. It was part of the mind games.

To stay safe, he lived in a constant state of alert, always on guard, never letting himself become lulled into complacency.

“It required a certain adrenaline,” Marc said. “You’re kind of like the rabbit in the field that’s nice and luscious, but you know there are wolves and coyotes and eagles.

“It could just change in a moment.”

Although there was an occasional sense of community in the labor camp, he knew it wouldn’t last.

He likened it to a Russian slogan he had heard: You never really make a friend in a Russian prison.

But Marc did make a friend on the outside.

Not long into Marc’s time at Rybinsk, a Russian human rights attorney started to visit him regularly.

Always dressed in a Louis Vuitton jacket paired with Italian shoes, the man spoke perfect English through sparkling white teeth.

Marc was warned by nearly everyone to be careful. The U.S. Embassy thought the lawyer was probably part of the KGB Russian intelligence service, but Marc didn’t care.

“He was nice to me,” he said.

The lawyer sometimes slipped Marc a piece of gum and took letters out of the prison to mail for him.

“He pulled strings for me,” Marc said, including getting him into the better barracks.

Maybe the best thing he did was to help Marc obtain consent to visit the colony’s church — a small Eastern Orthodox house of worship.

Other inmates told Marc they had sought permission for years to no avail. But, with the help of the lawyer, Marc was allowed to visit the chapel nearly every day.

“This guy would come and get me, and we would go to the church, and I would meet other people, other foreigners, and we would have time there,” Fogel said. “He was a great help.”

Although he was raised Catholic, Marc did not attend services regularly in adulthood. That changed at Rybinsk.

“I would sit on a chair and pray and try to take my mind off things,” he said. “Or I could be alone sometimes in there.”

The church was filled with icons of saints, the Virgin Mary and the apostles.

“I found St. Mark up there,” he said of his namesake, the patron saint of Venice, notaries, lawyers — and prisoners. “I always prayed to St. Mark.”

He attended a monthly Mass. Sometimes when it snowed, Marc swept or shoveled or chipped away the ice around the church.

One day, as the bells rang to signal the start of Mass, a group of people who frequently visited prisoners and someone who spoke English, invited Marc to a small house nearby after the service.

“So they listened to my story, and they invited me in the warm house to eat, have tea,” Marc said.

There was a wood-burning stove, food and company. Artists who painted the religious icons at the church would come there from the labor colony.

At the gatherings after Mass, up to 20 prisoners would join priests and the others who lived nearby to gather around a nice table and dine on pierogies, chocolates, brownies, cake and other small bites.

Sometimes, Marc was given fresh tomatoes, cucumbers, apples and mint, even fresh honey.

He also occasionally received books.

Marc’s books were the one constant keeping him sane.

When he was initially held in SIZO No. 5 in Moscow, Marc met a prison librarian who spoke English well. He had access to a stock of English-language novels.

“What do you need?” the man asked. “I’ll get your books.”

His family and colleagues in Moscow also sent him books. They could sometimes take months to make it through the jail’s censors.

At each new prison, even though his books had gone through screening at as many as five other facilities, the books always had to be checked again.

Marc read voraciously. He consumed Hemingway, Tom Clancy, Mike Tyson’s autobiography and the “Wisdom of Bruce Lee.”

To distract himself while awaiting trial, Marc devoured “A Prayer for Owen Meany” and one of his favorites, Abraham Verghese’s “Cutting for Stone.”

During one phone call with his mom from Rybinsk, she suggested Marc request a textbook.

“She said, ‘You know, Marc, you were never very good in math,’ ” he recalled. “‘Why don’t you get a geometry book and you could brush up on your geometry and algebra?’”

He read religious texts — the Quran and the New Testament. Russia’s great novelists, Chekhov, Dostoevsky, Tolstoy. He tore through “Anna Karenina” and “War and Peace” multiple times.

By his count, Marc read at least 172 books during his imprisonment.

Marc lugged the books from prison to prison during dozens of uncomfortable transfers.

“My back hurt. It was almost symbolically this huge weight that was on my shoulders — a bag of books that hurt me,” Marc said.

He called his books a blessing and a burden. “That bag of books becomes a heaven and hell in some ways.”

Often, Marc would read the books a first time, then go back a second and third, dog-earring pages, highlighting quotes that spoke to him.

“And then I would begin going through the book and writing all of these quotes down,” Marc said. “So I had notebooks upon notebooks of quotes from all of these books.

“And they took all of them.”

Any solace Marc found — in his books, the church, tea at the nearby house — was only temporary.

“It was just a battle that rarely had stopping points,” he said. “There were fleeting moments when you could be lost in something.

“But, man, when you lay down in bed at night to try to soothe yourself to sleep …” he said, his voice trailing off.

Even as an optimistic person with a great deal of love and support in his life, sometimes those negative thoughts would start to win.

“I would always tell my wife,” he said, “ ‘I could be sitting there and all of a sudden, I’m in this elevator flying down a mine shaft that’s dark, and I have no light, and I don’t know where it’s going to end.’ ”

When Marc started to spiral, he said, he knew he had to find ways to steady himself.

“Some people pull you out. The church pulled me out. Conversations on the phone,” he said. “I also knew that it could have been worse. Maybe that helped.”

Because Rybinsk was a high-security facility, prisoners were permitted only one visitor every three months.

Irina, Marc’s Russian translator friend from Moscow, was turned away the first time she went because one of his colleagues already had been there that quarter.

But Irina was able to get in to see Marc twice.

One visit took place in November 2023 when Marc was in the prison hospital. He spent more than 100 days there during his incarceration, mostly because of back spasms from a debilitating spinal condition that had led to three spinal fusions and a hip replacement before his arrest.

During Marc’s stay in pretrial detention, he was denied doctor visits but was administered dozens of injections without consent or knowledge of what they were. To this day, he has no idea what he was given.

Those injections continued at Rybinsk, where he also was losing muscle in his leg and arm. He developed neuropathy, numbness in his feet, causing him to fall.

Marc was hospitalized at the penal colony four times, likely because his Russian attorneys repeatedly filed medical complaints on his behalf.

When Irina and her husband arrived at the prison for their visit, they waited in a long line outside before finally being allowed in. The couple spent about four hours with their friend, talking sports, politics and family updates.

Marc asked them to write to then-first lady Jill Biden, who was also a teacher, hoping she might help. Irina’s husband did, though Biden never responded.

It was during another hospitalization in July 2024 that Russian television broadcast news that President Donald Trump, then a candidate, had been shot at a rally in Butler County, where Marc had grown up. Marc knew his mother was attending.

It was three days before he learned she was OK.

Marc didn’t know at the time, but Malphine had a brief exchange with Trump shortly before the shooting.

“He took my arm, and I told him (about Marc), and he said, ‘If I get in, I’ll get him out,’ ” Malphine said. “I said, ‘Just don’t forget his name.’ And he said, ‘I won’t forget. Marc Fogel.’ ”

When Irina visited Marc for the last time in October 2024, she found him in poor spirits.

His head had been shaved — Marc said an inspector wanting to assert his power ordered it — and he was distraught about being left behind in a vast prisoner swap that August between the U.S. and Russia that included Wall Street Journal reporter Evan Gershkovich and Marine veteran Paul Whelan.

“I just kept saying to him that he’s got to be strong. He’s his own counsel. He can’t give up because then everything will just lose its meaning,” Irina said.

She also relayed a message from Malphine, who was then 95: “Tell my son I will be there when he comes out.”

It brought Marc to tears.

For the rest of the four-hour visit, he and Irina just chatted.

“We were kind of like two friends catching up on lost time,” Irina said. “Sometimes we laughed, and sometimes he cried, and then it was time for me to go.

“Before I left, I said, ‘I just wish I could hug you.’ ”

But it was not allowed.

About a month after that visit, following Trump’s win in the presidential election, Irina wrote a prophetic letter to Marc. She told him she believed he would be freed after Trump took office.

“I said, ‘Your time is coming.’ ”

Over eight months, TribLive reporter Paula Reed Ward met with Marc Fogel a dozen times to talk about his experiences being held in the Russian prison system, his dramatic rescue and his ongoing adjustment to freedom.

Ward spent more than 20 hours in conversation with Fogel and interviewed his loved ones, attorneys, government officials and friends. She also reviewed Russian court documents and U.S. State Department filings.

This five-day exclusive series, which includes visuals from TribLive photographer Kristina Serafini, is the culmination of that reporting.

Paula Reed Ward joined TribLive in August 2020 as a courts reporter following a 17-year career at the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, where she was part of the team that won a Pulitzer Prize for its coverage of the synagogue shooting in Squirrel Hill.

Raised in Pleasant Hills, Paula attended Indiana University of Pennsylvania and majored in journalism. Her first job was at the Pottsville Republican & Evening Herald. She then spent five years as a police and courts reporter at the Savannah Morning News, in Savannah, Ga. It was there that she also earned a master’s degree in criminal justice.

Paula is an adjunct professor at Duquesne University and is also the author of the book “Death by Cyanide: The Murder of Dr. Autumn Klein.”

You can contact Paula at pward@triblive.com.