Hauntingly similar.

A little more than a century after a global influenza epidemic that cut a deadly path across Western Pennsylvania, that’s how Thomas Soltis describes the coronavirus pandemic that is spreading rapidly through much of Pennsylvania — having already killed 34 people in the state and more than 30,000 worldwide.

“Everything we saw in 1918 we’re seeing today: school closings, church closings, business closings,” said Soltis, a Westmoreland County Community College sociology professor who lectured on the 100th anniversary of the flu pandemic and wrote a book about its regional impact, “An Unwelcome Visit From the Spanish Lady.”

The 1918 disease was referred to as “Spanish influenza,” or the “Spanish Lady,” because the first newspaper reporting of the flu came in May 1918 from Spain, a neutral country in World War I and not subject to wartime press restrictions. The global pandemic went on to kill at least 50 million people — perhaps as many as 100 million, including nearly 700,000 Americans, according to researchers with the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“In some ways, it’s 1918 all over again,” he said — noting the business, entertainment and educational disruptions that are part of the social distancing strategy for curbing the health impact of covid-19. “We understand the medicine better and the transmission better, but there are some very similar happenings. We see the speed with which the disease is spreading and taking hold.”

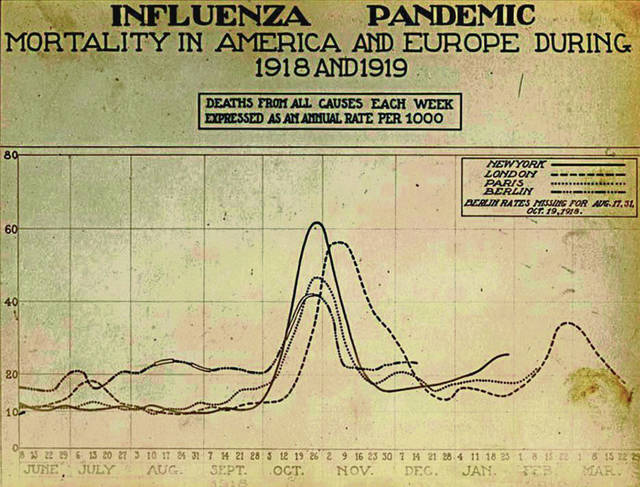

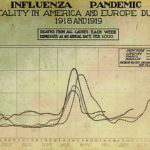

The 1918 flu arrived in three waves, stretching into early 1919. It killed about 50,000 Pennsylvanians, according to estimates cited by Soltis. The flu infected more than 90,000 and killed more than 2,000 in Westmoreland County, he said.

Pittsburgh had the highest death rate of any major U.S. city. The flu killed at least 4,500 people — more than one in every 100 residents. Nearly 24,000 people sought treatment at city hospitals.

At its height, a Pittsburgh resident contracted the flu every 70 seconds, with the illness claiming a life every 10 minutes, according to reports made to the city health department.

The Army commandeered Magee and Mercy hospitals and turned the Concordia Club in Oakland into a convalescent hospital for soldiers, many sickened while training on the University of Pittsburgh and Carnegie Mellon campuses.

The old county courthouse was turned into a temporary hospital, as was the Kingsley House in East Liberty, the Moose Lodge in Beechview, a Presbyterian church in Sewickley and a school auditorium in Edgeworth. A 300-bed tent went up in Westinghouse Park in Homewood, according to “Pittsburgh in the Great Epidemic of 1918,” a 1985 article by Kenneth White in the Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine.

Scores of other emergency hospitals popped up in communities from Natrona and Tarentum to Scottdale, Turtle Creek and Washington.

A sign posted outside Ligonier, where the entire town was quarantined, warned motorists: “You stop at your own peril.”

Then and now

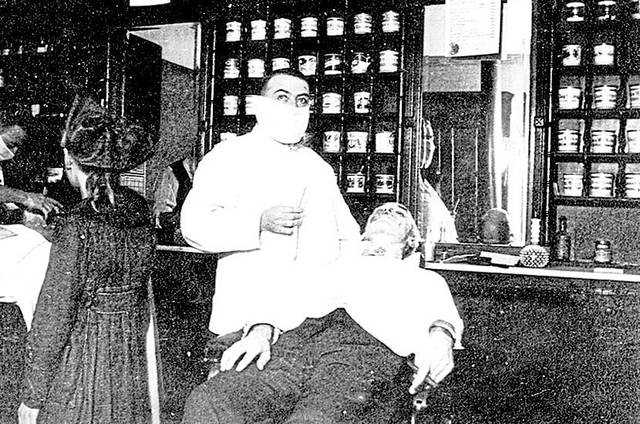

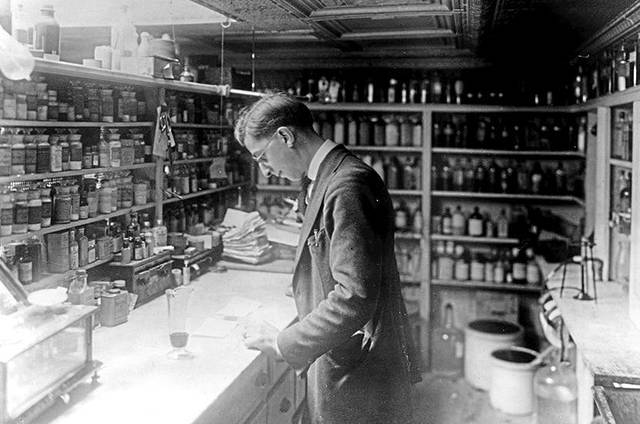

“In 1918, we did not have antibiotics, antivirals, ICU-level care, or even know that flu is caused by a virus,” said Dr. Amesh Adalja, a Pittsburgh-based infectious disease and critical care physician who is a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security.

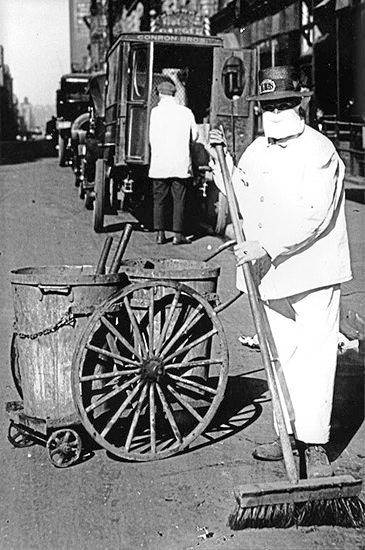

The Spanish flu pandemic “showed us how a respiratory spread virus could engulf the world” and “create a major disruptive event,” Adalja said. “It also showed us how targeted social distancing could be used to blunt the force of an outbreak in specific geographic areas.”

State and city officials in 1918 shuttered bars and saloons, billiard halls, theaters, cinemas and more. Schools and playgrounds closed, and church activities were canceled. College and high school football games were called off, as were parades and festivals.

While researching the flu pandemic, Soltis “always wondered what it felt like in 1918 to know that this disease was coming and there was nothing you could do to stop it,” he said. ”Now I know, and I don’t like it.”

While no demographic group has been spared from the effects of the coronavirus, the disease has been deemed most serious for older residents and those with deficient immune systems or other underlying health problems. In 1918, the influenza strain took a particularly cruel toll on people in the prime of their life, between ages 20 and 40.

Some specific groups — coal miners and pregnant women — were more susceptible to the 1918 disease, Soltis noted. “There was a doctor in Greensburg who saw 75% of his pregnant patients die,” he said.

The tragic story of a large New Jersey-based family that has lost four members to covid-19, including a Pennsylvania man who was the state’s first death, immediately brought to Soltis’ mind the devastating impact the Spanish flu had on the Hausele family in Pleasant Unity. In one week in November 1918, Charles Hausele Sr. lost eight family members to the flu — his wife, two daughters, four sons and a daughter-in-law.

One of the most unnerving things about the coronavirus is that researchers still have much to learn about it. In the face of that unknown, an Arizona couple ingested toxic fish tank cleaner, apparently believing one of its ingredients would be similar to a malaria drug that is being tested as a potential covid-19 treatment.

The 1918 flu was even more of mystery and Americans turned to a number of questionable would-be remedies.

“There were various onion cures and advice to drink a pint of whiskey,” Soltis said.

‘The other side’

Another covid-19 unknown, even with the $2 trillion federal rescue package, is how well the economy and working families will recover from widespread business closures and layoffs.

After the 1918 pandemic had run its course, Americans “tried to go back to normal as quickly as possible,” said Jeremy Youde, dean of the College of Liberal Arts at the University of Minnesota Duluth and an expert on global health politics.

While that occurred to a great extent, Youde noted it can be hard to distinguish the recovery following the flu pandemic from the recovery that followed America’s simultaneous involvement in World War I.

“Those shocks didn’t seem to be long-lasting or result in a dramatic altering of social or economic structures in the same sort of way were wondering about now,” he said. “One thing we saw in the immediate aftermath was that the average life expectancy dropped by 10 years. That seemed to go away relatively quickly as life got back to normal and as people were having children.”

Youde noted the 1918 pandemic provides a cautionary lesson in the health risks that can occur with attempts to return too quickly to life as it was before.

“We saw a lot of the same social distancing recommendations (in 1918), but we also saw where cities and local governments that were less stringent in their restrictions, or too quick to lift them, saw a resurgence (of infections),” he said. “If we lift these too quickly, we put ourselves at risk for the possibility of a second or third wave.”

One of the factors that distinguishes covid-19 from standard influenza viruses is that it is considered to be more contagious. Youde said, on average, each person with covid-19 could infect between 2.2 and 2.5 other people, while seasonal flu strains have an average contagion factor of 1.3 or less.

In comparison, according to a 2009 scholarly article, the 1918 flu is estimated to have spread to an average of between 1.4 and 2.8 people for every contagious person.

For Soltis, the 1918 pandemic provides some hope as well as apprehension for the months ahead. Though many Western Pennsylvania residents perished from that flu, communities ultimately rebounded.

“People lost their family members and lost their form of income, yet somehow they found the inner strength to carry on,” he said. “It shows the resilience of people. As difficult as it will be, we’ll get to the other side.”