As soon as nurses arrive for work at UPMC Altoona, they’re in constant motion.

In the hospital’s medical intensive care unit, which became the covid unit in March, the hallways are crowded with machinery, including IV pumps, dialysis machines and other equipment, said Paula Stellabotte, an ICU nurse.

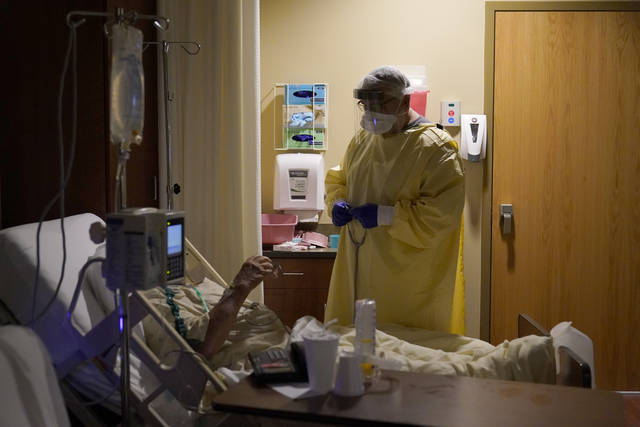

Stellabotte said the hospital staff keeps the equipment outside the covid rooms and threads wiring inside, positioning patients’ beds right up against the wall. It means nurses don’t have to layer on personal protective equipment every time they check on the machines, saving time and valuable resources.

The air is thick and hot, especially when nurses are suited up in plastic gowns for an hour or more, Stellabotte said.

The sound of the filters blasting, the machines buzzing and the frequent alarms and emergency calls throughout the building make the environment noisy and chaotic. Many patients have vitals that fluctuate unpredictably because of the virus, like blood pressure that plummets only to rise astronomically in a few hours’ time.

“You’re constantly checking, checking, checking,” Stellabotte said, and if her patients are doing OK, then she’s helping other nurses with theirs. It takes four people to safely prone a patient, she said (carefully turning them to lie on their stomachs when they have trouble breathing).

“It’s like you step onto a treadmill and you’re going, you’re going the whole time you’re there,” she said, “For basically 13 hours, you’re on fast-forward.”

The unit is crowded this week, Stellabotte said, with 14 covid patients. But virus patients are not contained in the unit anymore; there isn’t enough space for that at this point. Covid patients are present in several of the hospital’s ICUs, she said.

Stellabotte isn’t alone. Front-line workers across Western Pennsylvania hospitals have described intense workloads, diverted patients, crowded emergency departments and dwindling ICU bed availability. While leaders of the region’s hospital systems still project confidence in their ability to adjust, create more space and maintain care for patients, state officials on Thursday drew attention to the urgency in the region. In Southwestern Pennsylvania, a third of hospitals are anticipating staff shortages in the next week, Secretary of Health Rachel Levine announced.

“The people who make our health care system work are relying on you to do the right thing,” Levine said, imploring the public to follow safety protocols. “We all have a collective responsibility to each other.”

Managing staffing

The advantage of regional health systems, hospital leaders say, is in their ability to share resources such as staff, medicine and personal protective equipment. If one facility runs low, reinforcements can be dispatched.

“There are some hospitals that have a higher demand than others,” said Dr. Don Yealy, UPMC’s chair of emergency medicine, naming UPMC Altoona as a facility that stands out. “We enact plans not only to help the capacity at that individual facility but also how to use other assets within the system to help them.”

“But there’s really no facilities that are completely without demand, and that’s what’s different this time around,” Yealy added.

Stellabotte said some Altoona patients have been moved to UPMC facilities in Pittsburgh, which has been helpful. But as one of the largest facilities in the surrounding counties, she said, there are always more patients coming in. Her unit recently hired 22 travel nurses to help with the increased workload, she said.

Managing adequate staff is a struggle for several facilities in the area, thanks to increased patient population and the quantity of front-line workers getting exposed.

Dr. Brian Parker, chief quality and learning officer for Allegheny Health Network, said AHN has tried to be proactive about staffing challenges, “understanding that folks who work in our hospitals are subject to community spread, just like the rest of the population.” The network has been in a constant cycle of monitoring potential transmission in facilities, contact tracing and hiring travel nurses from agencies.

“We’ve always used a certain degree of agency nurses to cover,” Parker said, “but you can probably guess that every other health system is looking for additional folks to help.”

Hospitals also incentivize nurses to take on extra hours, offering monetary bonuses, for example. But many workers say taking the hours feels obligatory, if not mandatory, so that they don’t leave their co-workers in the lurch. On social media and in conversations with the Tribune-Review, many nurses said they have felt compelled to take on more work hours to meet the need.

Aside from the stress on staffing, many worry about finite quantities of beds, ventilators and space.

“My greatest fear is running out of equipment,” said Myra Taylor, a critical care nurse at Allegheny General Hospital. “I can keep pushing, but if I don’t have the equipment that I need, that makes it almost impossible to do it. I need for the government officials to make sure supplies do not run out.”

Hospitalizations have increased by 500% in the region since the spring. On Friday, Allegheny County had only 11% of ICU beds available, according to the Department of Health, amounting to 91 beds. There are 663 covid-19 patients hospitalized in the county, 188 of whom are in intensive care and 97 of whom are on ventilators.

Concerns over ventilator capacity and bed availability prompted contingency plans early in the pandemic, Parker said. The plans included placing two patients on a single ventilator, setting up triage tents or trailers, or diverting patients from emergency rooms. Parker said he is unaware of any of that happening within AHN at the present, but the organization is prepared to take such steps.

Parker said the network has had to “decompress” certain facilities — naming Forbes Hospital in Monroeville as an example — by moving some patients to other hospitals to control capacity.

Hospitals fill up when their geographic area is experiencing more community spread, he said. But what’s different about now compared with the spring is that every facility is experiencing the rapid influx.

“Now, you really can’t distinguish anything. It’s much more widespread here in Southwestern Pennsylvania,” he said. “We all are seeing it in all of the communities now, which I think is why we also made the decision to peel back our visitation policy.”

AHN updated its policy Dec. 1; visitors may now see patients only in certain units or circumstances. UPMC and Excela Health also recently updated their policies.

There were 300 covid-19 patients across Allegheny Health Network as of Friday, a spokeswoman said, with about 100 in intensive care.

UPMC has more than 1,000 covid patients across its system, 393 of which are in Southwestern Pennsylvania. A UPMC spokewoman said 242 covid patients are in the Altoona region and Maryland.

Yealy said he monitors an internal dashboard to assess ICU capacity at individual sites, watching what is being used and what is available. From there, he said, UPMC can call on other places that can serve equally as an ICU and can redeploy existing beds.

Hospital leaders are still confident about their ability to adapt and meet the needs of the region, but in practice, front-line workers say it’s getting more and more challenging.

“That’s not our reality,” Stellabotte said. “There are patients on floors that should be in the ICU that we don’t have a bed for. It’s scary.”

When asked by a Tribune-Review reporter about staff and ICU capacity, Excela Health said PPE and ventilator capacity are at “very good levels” and the system is adapting daily.

“Capacity management is fluid as our nurses, physicians and staff face increasing covid volumes and other hospitalizations as well as personal illnesses,” Dr. Carol Fox, chief medical officer, said in a statement. “These are indeed challenging times for everyone in health care, and our staff remains the single most important factor in our ability to provide care.”

Emotional toll

The constant motion and inevitable fatigue takes an emotional toll on front-line workers.

“We’re watching patients who have covid deteriorate rapidly,” said Katrina Rectenwald, another critical care nurse at Allegheny General. “Quite frankly, every patient leaves a mark on you, and when you see somebody deteriorate that rapidly and there’s something that could’ve been done to prevent that, you carry that with you.”

Stellabotte, in Altoona, said she used to play the radio on her drive home. She would call her mother and talk. But now, she doesn’t want to do either. She avoids rehashing the day, and she avoids sounds, even music.

“I just want quiet,” she said.

Having worked in nursing for 41 years, Stellabotte is in a position where she could likely retire if she wished. Some nurses have quit, she said, or moved to other units because they didn’t want to be in the environment anymore. Stellabotte said she is committed to ride this out. She doesn’t want to abandon the other nurses on her unit, who would struggle more without her help. She doesn’t want to step down when she feels the community needs her most.