Jordan Brown lost seven years of his childhood.

He spent from ages 11 to 18 in the custody of the state of Pennsylvania, accused — and later convicted — of a murder he maintains he didn’t commit.

Now, six years after the state Supreme Court reversed his conviction, Brown is facing a trial of a different sort.

This one, to be held in federal court in Pittsburgh, will determine what, if any, money Brown ought to be paid for those lost years.

In July 2020, he sued the four Pennsylvania State Police troopers who led the investigation against him, alleging civil rights violations, including malicious prosecution.

Brown asserts that the troopers fabricated the claims against him and withheld exculpatory evidence from the affidavit of probable cause used to charge him.

“Ultimately, the (state police) defendants targeted Jordan, who they knew was innocent,” the lawsuit said. “They fabricated reports and manufactured evidence against him, culminating in a falsified criminal narrative that stole his entire childhood.”

State police have denied the allegations.

The trial, expected to last about two weeks, is scheduled to begin Tuesday before U.S. District Judge W. Scott Hardy.

It will be separated into two phases. First, the jury must determine liability. If the panel agrees the state police violated Brown’s rights, then it will hear evidence about how much to award in damages.

“There is no amount of money that can restore a childhood that was taken away from him,” said Stephen Colafella, a lawyer who represented Brown in his criminal case. “The lack of evidence and the haste with which the decision was made to charge him is inexcusable.”

The investigation

On Feb. 20, 2009, Kenzie Houk, who was eight months pregnant, was shot to death while lying in bed at her Wampum, Lawrence County, home.

Chris Brown, Houk’s boyfriend, had been at work since 7 a.m., and his son, Jordan, and Houk’s 7-year-old daughter had left home to catch the bus for school at 8:12 a.m.

Around 9:30 a.m., a crew doing work on the property saw Houk’s 4-year-old daughter crying at the front door. They called police. First responders arrived at 10:13 a.m.

Houk, 26, had been killed with a shotgun blast to the back of her head.

From the start, according to Jordan Brown’s civil attorneys, the investigation was problematic.

The lawsuit alleges that the crime scene was immediately contaminated by the first officers to arrive.

Although they attempted life-saving measures, one of the officers became physically ill and tracked blood and other evidence throughout the house, the lawsuit said. The plaintiffs also allege that the outside of the rented farmhouse and its 40 acres were not properly secured, and so any tire tracks or other evidence was also lost.

The lawsuit said that police never found any physical evidence to link Brown to the crime, and that they ignored substantial evidence that pointed to Houk’s ex-boyfriend.

Instead of investigating the ex, who had learned within the previous two weeks he was not the father of Houk’s youngest daughter, the state police quickly focused their attention on 11-year-old Jordan, then a fifth-grader at Mohawk Elementary School, the complaint said.

Investigators said that Houk was killed with a shotgun, and Brown had received a youth model, 20-gauge shotgun as a gift from his father. Brown used it to win a turkey shoot the preceding weekend.

State police surmised that Brown used his shotgun to kill Houk and then left to go to school.

However, according to the lawsuit, the only evidence against him was the fourth statement given by Houk’s 7-year-old daughter after 12:15 a.m. on Feb. 21, 2009.

“By that time, the (state police) defendants had carefully crafted a false criminal narrative that Jordan had the means and opportunity to murder Kenzie Houk, and that he in fact committed the murder,” the lawsuit said.

The plaintiffs allege that the girl spoke to the police three times before that — though none of those interviews were recorded — telling them she didn’t see or hear anything unusual that morning before leaving for school.

However, Brown alleges, by the third interview, the state police pressured the girl into changing her story — including that she saw Brown come down the steps that morning “carrying his two guns,” that she then saw him take them back upstairs, and that she heard a “big boom” before Brown joined her to leave for the bus.

The lawsuit accuses the state police of then rehearsing with the girl the key facts they wanted to use against Brown.

By the time investigators conducted their fourth interview of the 7-year-old girl, who had learned that day that her mother was dead, she had been awake for almost 16 hours, the lawsuit said. She had also been taken to multiple places for “care, maintenance and interviews.”

The fourth interview was recorded and cited extensively in the affidavit of probable cause — though none of the information that might have been helpful to Brown from any of the girl’s earlier statements was included, the lawsuit said.

Brown was charged by 3 a.m. — just 16 hours after Houk was killed.

In answering the claims in the lawsuit, state police denied that the investigation was inadequate, that they targeted Brown or knew that he was innocent.

A state police spokesman said the agency could not comment on pending litigation.

The court case

After Brown was charged, the Lawrence County District Attorney’s Office attempted to try him as an adult, a decision at first upheld in court.

The initial judge on the case refused to transfer the case to juvenile court, finding that Brown’s consistent denials of guilt made him unlikely to respond to rehabilitation — a goal of juvenile court proceedings — since the state must release young offenders at age 21.

However, Brown appealed, and the state Superior Court said that the lower-court judge’s decision violated Brown’s right against self incrimination.

Ultimately, the case was moved to juvenile court and went to trial in April 2012.

By that point, Brown had already been in custody for more than three years.

He was adjudicated delinquent of first-degree murder, and ordered to remain incarcerated until age 21.

A yearslong series of appeals sent the case back to the juvenile court judge twice. In 2018, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court ruled in a 47-page opinion that the evidence presented by the prosecution against Brown was insufficient to overcome his presumption of innocence.

By that point, Brown had already been released from custody for two years.

His father, at a news conference five days after the court reversed his son’s conviction, said it was “bittersweet.

“(I was) overwhelmed with joy but still full of sorrow knowing that we won’t have closure in the loss,” he said.

Houk’s family continues to believe that Brown is responsible for her death.

“We’re just praying for the truth to prevail,” said Houk’s sister, Jennifer Kraner, on Sunday. “It’s not OK for him to do what he’s doing.”

Since Brown’s conviction was overturned, Houk’s father has died, Kraner said. She is frustrated that there will be another trial. She is expected to be a witness.

“I think it’s awful that he’s doing this for money, and they have to continue to live through this nightmare,” Kraner said of her nieces and mom.

“Justice can never really be served because nothing can bring her back,” Kraner said.

The lawsuit

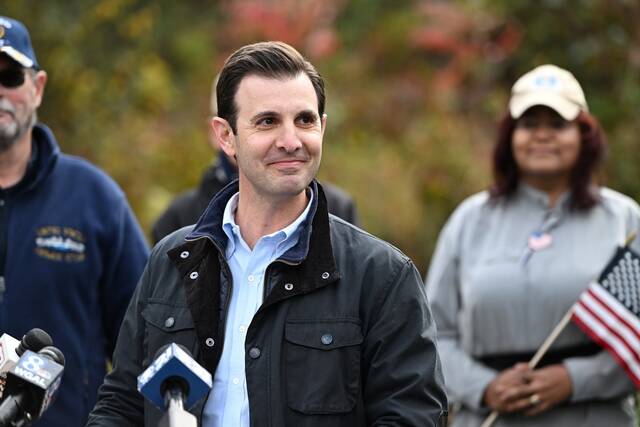

Brown, who runs a beer distributor with his father, filed his lawsuit nearly two years after the state Supreme Court threw out his conviction.

The defendants include troopers Janice Wilson, Jeffrey Martin, Troy Steinheiser and Robert McGraw, who has since died.

Former state police Commissioner Frank Pawlowski was also named, but has since been dismissed from the case.

Among the allegations, Brown’s attorneys said that the state police failed to properly investigate Houk’s former boyfriend who had been violent with her and had been the subject of a restraining order.

The lawsuit also alleges that the state police failed to follow proper procedures in how they interviewed Houk’s 7-year-old daughter and that they misstated an interview given by Chris Brown’s ex-girlfriend, writing in a report that the woman said she had been afraid of Jordan, even though a transcript of her interview said exactly the opposite.

Alec Wright, who is representing Brown in his lawsuit, said this case is a way for him to get justice.

“Jordan Brown never committed this crime and the defendants, as well as the governor’s office, know it,” Wright said. “(T)his case is our chance to set the record straight once and for all that Jordan is innocent.”

If the case gets to a damages phase, it is likely there will be testimony about Brown’s experiences at college. He was initially accepted to attend Edinboro University, but days before he was to move in, the school sent him a rejection letter, citing his history.

He later attended Youngstown State University.

Among the witnesses expected to be called at trial are those who knew Brown in college. They will likely testify about the damage to Brown’s reputation when his fellow students learned about his arrest.

“That’s going to be attached to his name for life,” Colafella said. “You just can’t erase it.”

What’s at stake

Joel Sansone, a civil rights attorney in Pittsburgh, has battled against the state police in a number of cases in federal court.

One high-profile case was the shooting death of 12-year-old Michael Ellerbe in Uniontown on Christmas Eve 2002.

Troopers Samuel Nassan and Juan Curry were chasing Ellerbe, who was unarmed. Curry’s gun accidentally discharged as he tried to scale a fence, and Nassan claimed he believed the boy fired at his partner.

Nassan shot and killed Ellerbe.

A jury awarded Ellerbe’s family $28 million in 2008, although the case settled several months later for $12.5 million.

Damages are often the result of the jury’s collective common sense, Sansone said.

“Juries don’t want to punish police officers,” he said. “Everybody wants to believe the police are there to protect us. They don’t want to believe there are monsters out there.”

Winning a civil rights case against law enforcement is difficult, and plaintiffs are successful less than 15% of the time, Sansone said.

“Taking a case against any police officer in Western Pennsylvania is extremely difficult, but especially so versus the Pennsylvania State Police because there’s this aura about them where people think of them as elite police officers,” Sansone said.

It can help a plaintiff’s case, he continued, if they get access to the disciplinary files of the officers involved, but some judges won’t allow that.

In a civil trial, Sansone said, cross-examination of the officers involved can win or lose the case.

“You’ve got to make the police officer the bad guy,” he said.

No compensation in PA

According to the National Registry of Exonerations, 176 people in Pennsylvania have been exonerated for crimes they didn’t commit.

The database does not include Jordan Brown’s case, however, as the registry requires the discovery of new, favorable evidence.

Brown’s conviction was overturned based on insufficient evidence.

According to the registry, 12 states, including Pennsylvania, do not provide any compensation to those who have been wrongfully convicted.

Last year, a bill was introduced in the state House that would have provided $100,000 for each year of imprisonment while awaiting a death sentence, or $75,000 for each year of standard imprisonment.

The legislation passed out of the judiciary committee in October 2023 but was never taken up by the full House.

Wright, Brown’s attorney, said the issue goes deeper than just providing money to those who are wrongfully convicted.

“The deeper, root issues lie in our public servants, like law enforcement and other government officials, who do not take the time or care necessary to see what went wrong, how it went wrong and why the system was able to wrongfully convict one of us — in this case, an innocent 11-year-old boy,” he said. “These are tough discussions that require tough reflection with tough accountability.”

In Brown’s case, Wright said, those things have been absent.

“And now Jordan has to put his faith in a system that let him down so badly before just to try to get justice on paper.”