As Joseph Albert “Jock” Yablonski began his 1969 campaign for the presidency of the United Mine Workers of America, he was confident that he had picked the right time to challenge incumbent W.A. “Tony” Boyle, who he believed was not in touch with the miners.

“My dad had the power base, and when it came time to take on Boyle, he took him on,” said Yablonski’s last surviving son, Chip, at his home in Bethesda, Md. “There was no one who had administrative experience that was elected and had shown a relationship between their role in the union and the membership. My dad had that.”

The campaign stretched from summer to fall and became increasingly brutal.

As soon as Jock Yablonski, who lived in Clarksville, Washington County, declared his candidacy, Boyle had his goons stalking him wherever he went. Yablonski was going into the coal fields to campaign almost every weekend from June to early December, and he posed a considerable threat to Boyle’s corrupt regime.

On New Year’s Eve 1969, Jock Yablonski, his wife, Margaret, and 25-year-old daughter, Charlotte, were killed in the family’s farmhouse.

Leading up to his death, he knew that his life was in danger. He pressed on with his campaign all the while knowing shady characters had been following him.

Early in the campaign, after speaking to what he thought was a group of supporters in Springfield, Ill., Jock Yablonski was attacked by an assailant who was on Boyle’s payroll. He was knocked unconscious and thought he was paralyzed. He realized later that he had been set up.

Knowing he was in a fight he might well lose, Boyle met with Albert Pass, secretary-treasurer of UMWA District 19 in East Tennessee and Kentucky. Pass came up with a plan to hire three men from Cleveland to kill Yablonski. They were Paul Gilly, Aubran “Buddy” Martin and Claude Vealey, and they ended up splitting $20,000 later found to have been embezzled from the UMWA.

“He wasn’t frozen (with fear). He was a 59-year-old man beaten up in Illinois. But he kept going into places that could have been hostile. That really takes courage. I can’t imagine,” Chip Yablonski said. “There were celebrated stories of guys threatening him with weapons and he told one of them from eastern Kentucky, ‘I’ll take that gun and shove it down your goddamned throat.’ ”

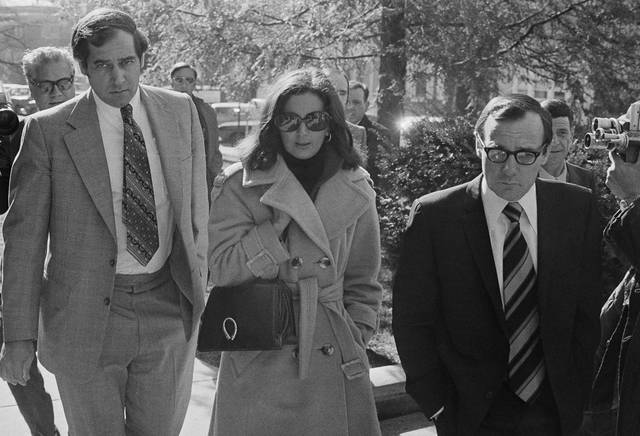

With all of the campaign violence and threats being made, Jock Yablonski and his lawyer, Joe Rauh, asked Labor Secretary George Shultz to investigate. They knew that Boyle was engaged in illegal activity, including bribes and intimidation. But he was repeatedly told that nothing could be done until after the election.

The election was held Dec. 9, and Boyle defeated Jock Yablonski by a landslide, a nearly 2-to-1 margin. But on Dec. 18, Yablonski asked the U.S. Department of Labor to conduct a fraud investigation. He vowed not to give up and believed there was a good chance the results would be overturned. That possibility undoubtedly concerned Boyle.

The murders

Three weeks later, Gilly, Martin and Vealey converged on Jock Yablonski’s Clarksville farmhouse. Up to that point, they had proven to be a clumsy and inept threesome. They had been following him for months. The plan was to corner Jock Yablonski and carry out an assassination. The gunmen had driven from Ohio to Clarksville, then to Washington, D.C., to Scranton and back to Clarksville but had failed in their attempts to this point.

Into the early-morning hours of Dec. 31, 1969, they watched from a hillside, drinking beer and booze until the lights of the house went out. They drove a blue 1966 Chevy with Ohio plates alongside the home and broke in through the back door.

Gilly, Martin and Vealey quietly made their way up the winding wooden staircase to the bedrooms. Martin went to the bedroom where Charlotte was sleeping and shot her in the head.

“The bullet she took in the back of her head could have been me a day earlier,” Chip Yablonski said. “She was sleeping in my bed the night she was murdered.”

Indeed, Chip Yablonski had been making a holiday visit and slept in that same room the night before. He left the following afternoon to attend a New Year’s Eve celebration in Virginia.

The killers then crept into Jock and Margaret’s bedroom and shot them both. The bodies weren’t found for several days.

Chip’s older brother, Ken, was worried because no one had heard from his parents. On Jan. 5, 1970, he drove from his law office in Washington, Pa., to Clarksville, where he made the gruesome discovery.

Chip Yablonski was at his law office in Washington, D.C., when he received a phone call informing him that his father, mother and sister had been slain. He picked up his wife, Shirley, at the school where she was teaching and their son, Jeffrey. They boarded a plane for Pittsburgh.

It was a hectic period for the surviving brothers. They had learned of the deaths of their parents and sister on Monday and buried them on Friday.

During the four days in between, they were making arrangements with a funeral home as they waited for the bodies to be released by the county coroner, picking out caskets and walking through knee-deep snow choosing cemetery plots.

“It was really just horrendous,” Chip Yablonski said.

Monsignor Charles Owen Rice presided at the funeral in Immaculate Conception Church in Washington, Pa. As he spoke, Rice compared Jock Yablonski to other iconic leaders who had been assassinated during the 1960s, including Martin Luther King Jr. and Bobby Kennedy.

Coal miners carried Jock Yablonski’s casket. Upon hearing the news of the killings days earlier, thousands of them went on strike.

Chip and Ken Yablonski focused on getting the FBI to launch an investigation.

“My dad, my mother and my sister sacrificed for what he believed in. At that point, we were committed,” Chip Yablonski said. “We were not going to let this sit. We were convinced at the very beginning that District 19 and Albert Pass were involved. We were Jock’s sons, and we were not going to rest. We were single-minded.”

The investigation

It wasn’t long before Gilly, Martin and Vealey were arrested in Ohio. Gilly and Vealey confessed to the murders. It then became a matter of law enforcement officials making the connection to Boyle and others running the UMWA.

Pittsburgh FBI agents initially refused to get involved. At the time, J. Edgar Hoover was still the director of the FBI, and he didn’t like unions.

“Hoover didn’t want anything to do with it,” Chip Yablonski said. “He wanted the locals to handle it.”

Meanwhile, Joe Rauh, Jock Yablonski’s lawyer, pressured U.S. Attorney General John Mitchell to get the Justice Department involved.

“(Joe) went to the Justice Department because the Labor Department had totally screwed this up by ignoring my dad and Joe Rauh’s pleas,” Chip Yablonski said. “For six months, Joe said repeatedly, ‘This violence will beget more violence.’ ”

Mitchell had an idea that the murders were connected to the union election. He got word to Pennsylvania Gov. Raymond Shafer to send him an official request. With Shafer’s letter in hand, Mitchell ordered the FBI to open an investigation.

Over the next few years, the dominoes began to fall.

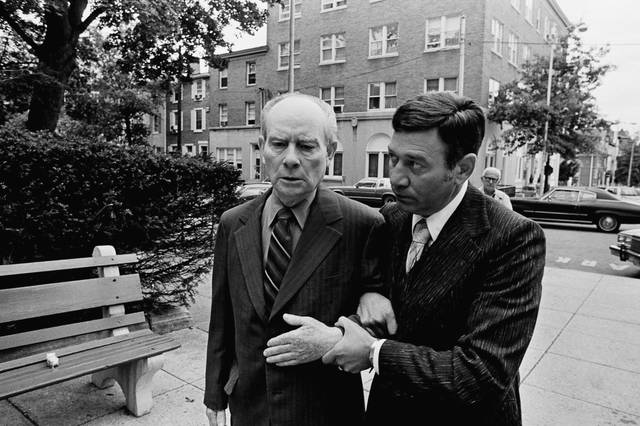

In 1973, Boyle was arrested on first-degree murder charges. Gilly agreed to cooperate with the prosecution and appear as a commonwealth witness in Boyle’s trial the following year. He was found guilty and sentenced to three life terms. Though the Pennsylvania Supreme Court overturned the conviction in 1977, Boyle was tried again and found guilty once more. He died in prison in 1985.

In all, seven men and one woman were charged with three counts of murder for the slayings of Jock, Margaret and Charlotte Yablonski. They included Albert Pass, the secretary-treasurer of UMWA District 19, who saw that the murder plan was carried out.

The Yablonski legacy

“Had he lived, Jock Yablonski probably would have ascended to the UMWA presidency,” said Charles McCollester, a retired professor of industrial and labor relations at Indiana University of Pennsylvania. “He was tough. The Federal Mine Safety and Health Act of 1977 is a direct result of Yablonski.”

He also was instrumental in getting victims of black lung compensated under federal law.

The results of the 1969 UMWA election were overturned by U.S. District Court Judge William B. Bryant on the grounds of “massive vote fraud and financial manipulation.”

Another election was held in 1972. Arnold Miller, a veteran coal miner who had been diagnosed with black lung disease, defeated Boyle by 14,000 votes.

“Unfortunately, it took Jock Yablonski’s death to start the democratic reform of the United Mine Workers of America,” said former District 4 and District 2 president Ed Yankovich. “When he died, rank-and-file miners got together and said, ‘Enough of this.’ ”

Chip Yablonski was appointed general counsel of the UMWA and worked with his brother and others to form Miners for Democracy, a reform movement within the union.

Changes that followed included union members electing local and district leaders and voting on contracts, something Jock Yablonski had pushed for. Health and safety standards for miners were bolstered as well.

“I have so much respect for Chip. His dedication to union principles in spite of the fact of everything that his family had gone through is really remarkable,” said former District 2 president Nick Molnar. “I’ve never met Chip but, to me, just having Jock’s son there was really something.”

By 1975, Chip Yablonski was ready to move on.

He went on to work as outside counsel for the National Football League Players Association, among other labor groups.

“What I miss is when you succeed in something and you have what you think is an enormous success, like when I took on a mining case in Central Pennsylvania in the heart of nonunion coal country and managed to get $2.5 million for a widow and her kids, I wanted to be able to call my dad and say, ‘You won’t believe this. …’ I miss that.”