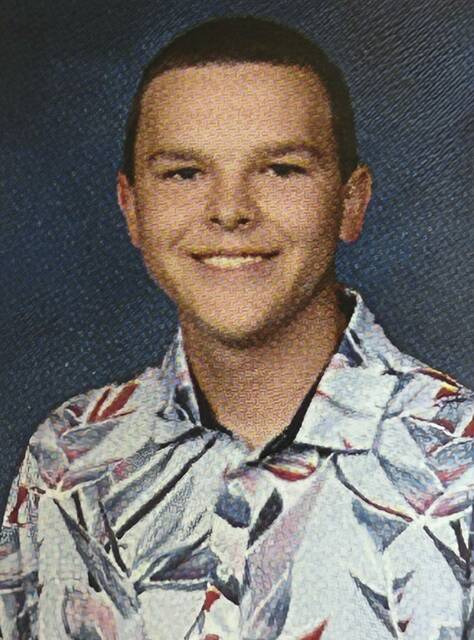

Catholic school taught Jim Scafuri as much about how to take a beating from a nun as math or reading, so when he started at the public Morningside Elementary School in the 1960s, it came as a welcome reprieve.

“I started to learn for the first time in my life,” the 75-year-old recalled. The A’s and B’s followed.

Almost 60 years later, he turned to the angular brick fortress on Jancey Street to rescue him once more — this time from what he said was a rundown senior high-rise in Blawnox.

It took four years on the wait list, but in 2021, he got the call: He’d be moving into one of 46 senior apartments inside or attached to his old school.

Scafuri’s boomerang experience isn’t all that unusual at Morningside Crossing — or any of the dozen or so vacant schools turn senior apartments across Southwestern Pennsylvania.

These projects are viewed, for the most part, as a two-birds, one-stone solution to the region’s aging population and glut of empty schools. There was a distant time, noted University of Pittsburgh regional economist Chris Briem, when Pittsburgh-area communities scrambled to build schools, often on prime lots.

A lot has changed since those days.

“We clearly have entered a realm where we have too much old school infrastructure, and we do have an older age demographic, so it’s a very logical conversation,” Briem said.

Indeed, the area’s population of people 65 and older rose from 407,000 to 493,000 between 2010 and 2020, while dozens of schools have shuttered.

If Pittsburgh Public Schools follows through on restructuring recommendations, another 12 could go on the market in the coming years.

Addressing both demographic realities makes sense, said Kevin Progar, a public policy expert and former initiative director at the Center for Community Investment, and can help add much needed senior housing to the market.

Charming stories about residents going full circle or former schools being reborn come as a welcome bonus.

“There’s community value in the perception of a place,” Progar said. “What that means emotionally has real value, but it doesn’t show up on a spreadsheet in any way.”

Inside a converted school

Just a few years ago, the old East Vandergrift Elementary School was an eyesore on the tiny town’s main street, McKinley Avenue.

The awning was tattered. Bricks were falling out. In case anyone didn’t get the message, a “condemned” label was slapped on the front doors.

“We tried to keep as much of it as we could,” said Trey Barbour, senior vice president of development for Pivotal Housing Partners, as he showed off the renovated building. “But it was in really bad shape.”

Residents 62 and older have started moving into the Morning Sun Senior Lofts. As with many of these senior housing complexes, tenants must receive 60% or less of the area’s median income.

Some are living in repurposed classrooms, while others have taken up residence in a newly built wing where the gymnasium and cafeteria once stood. The auditorium lives on as a spacious community room, envisioned by Barbour as somewhere for residents to mingle or entertain family.

“It’s just a great building to live in,” said Dora Gibson, who was the first tenant to sign a lease at the lofts. “It’s everything I thought it would be.”

The project took several years and $17 million to complete. Around 80% of the cost was handled through the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s Low-Income Housing Tax Credit program.

The building’s sturdy craftsmanship and simple layout made it an attractive target for Pivotal, even after a few denials by HUD. Some older schools, especially those constructed in the 1950s and ’60s, were designed as bomb shelters.

But there’s almost always a trade-off in the form of multimillion-dollar asbestos and lead paint abatement as well as accessibility updates.

East Vandergrift Elementary, constructed in the 1930s, lacked an elevator, for example.

Those factors can add up and lead a developer to raze the building altogether.

The Armstrong County Industrial Development Council funded this year’s demolition of the old Apollo High School, with plans to pass the site along to Pivotal to build affordable senior housing, pending zoning approval.

And, in Penn Hills, Gatesburg Road Development wants to give itself a clean slate to build 48 units for low-income seniors in the footprint of what was once William Penn Elementary School.

Schools can be too big, too small, too old or too new for retrofitting, explained Andrew Haines, executive vice president of Gatesburg Road.

Winding hallways can waste square footage, and decades of additions can muck up construction plans beyond the point of feasibility.

As for the old William Penn Elementary School, a one-story box from the 1940s, “we couldn’t get enough units on it to make it work economically,” Haines said.

A dearth of senior apartments

Since 1999, Pittsburgh-based Integra Realty Resources has logged 116 completed or in-progress senior apartment complexes in the region.

Allegheny County has seen the lion’s share of development, with 55 finished projects and 15 in various stages of planning and construction, as of March.

In a distant second place lies Westmoreland County, with nine developments built and two on the way. That’s about 16% as many projects as Allegheny County has seen, despite Westmoreland County having a senior population 34% as large.

Experts say there are too few senior apartments in the region, and the ones that are out there often are too expensive for many seniors or don’t meet their desire to stay in the communities they call home.

Newer senior apartments represent a crucial middle ground between seniors staying in homes they can no longer keep up with and more nursing home-like settings.

That’s especially true in the Pittsburgh area, according to Joe Angelelli, president of the Southwestern Pennsylvania Partnership on Aging, who noted much of the housing stock was built with lots of steps and without accessibility in mind.

The apartments that do exist are “being built in corridors that have more money,” Angelelli said. “It’s the dying towns that have nothing around them that there’s nowhere to go.”

School-to-senior housing conversions buck this trend, to some extent. A TribLive analysis turned up several projects in low- to moderate-income areas, such as Glassport, Carnegie and Duquesne in Allegheny County, though few have been built in outlying counties.

For struggling communities, senior housing can spark — or at least speed along — a broader economic upswing.

In Mt. Washington, a Pittsburgh neighborhood on the upswing, developer A.M. Rodriguez Associates retrofitted the former South Hills High School as mixed-use senior housing.

When construction finished in 2010, homes in the area were selling for about $40,000, claimed the company’s president, Victor Rodriguez.

“Within two years of completion, those homes were worth $140,000, and now, they’re selling for $300,000,” he said. “If you take away these big dilapidated structures, it really changes that perspective.”

Michael Carlin, executive director of the Mount Washington Community Development Corp., corroborated the massive hikes in real estate prices, though he was quick to note the South Hills High School project and two schools converted into family housing likely played only a minor part.

Uses abound

Senior housing makes for a neat demographic fit when it comes to empty schools in Southwestern Pennsylvania, but these vacant structures can take on a variety of second lives.

In Pittsburgh’s Hill District, the old Madison Elementary School has become the home of the Pittsburgh Playwrights Theatre Company, complete with a 99-seat theater, offices and rehearsal space.

What was once Chatham Elementary School in the city’s North Side now contains a community service organization, a home health aide agency and a personal training center.

A good chunk of schools go on to become market-rate housing geared toward families, like Bowtie High School in Homestead, which earned the developers several generous “take a look inside” articles from national business publications.

“I don’t know if schools are standout touch points (in a community),” said Marimba Milliones, president and CEO of the Hill District Community Development Corporations. “But they are standout opportunities because of the scale of them.”