“We have safely crossed the pond.”

With that telegram, Navy Lt. Cmdr. Albert C. Read announced to the world the first transatlantic flight in 1919 — eight years before Charles Lindbergh’s solo, nonstop voyage.

One of Read’s crewmen on the NC-4 seaplane was a Somerset County native by the name of Eugene S. Rhoads, a chief machinist’s mate in the Navy’s Seaplane Division One.

Rhoads’ four Pittsburgh-area grandchildren — Kathleen Martin of Gibsonia; Michael Hackett of Pittsburgh; Douglas Hackett of Wheeling, W.Va.; and Brian Hackett of Allison Park — will be among those celebrating the 100th anniversary of the historic flight Wednesday.

“It’s kind of cool for the family,” said Len Martin, husband of Kathleen Martin and family historian. “It’s probably the most famous air accomplishment that nobody knows about.”

Rhoads, who died in 1975, unexpectedly found himself part of the Navy’s effort to claim bragging rights as sponsor of the first flight across the Atlantic Ocean.

At age 27, Rhoads became a last-minute replacement for a flight engineer who lost a hand in a propeller accident six days before the May 8, 1919, departure, Martin said. That unfortunate incident thrust Rhoads, a young man from Somerset, into a part of aviation history.

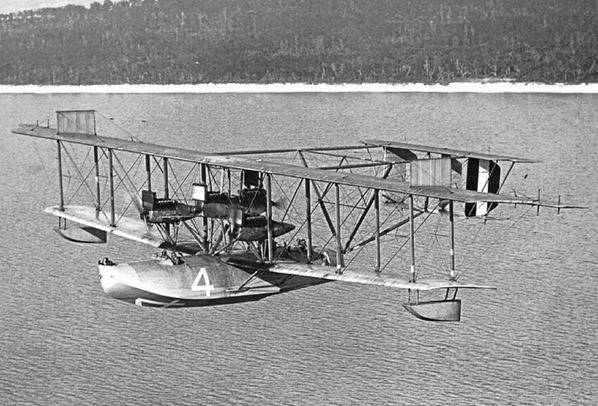

The NC-4 was developed out of a Navy collaboration with the Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Co. during World War I. The idea was to develop a cargo plane that could fly long distances and avoid the threat of a German submarine attack.

After the war, four NC (Navy/Curtiss) flying boats were commissioned. Only three — NC-1, NC-3 and NC-4 — were ready to go by the time of departure from the Rockaway Naval Air Station on Long Island, N.Y.

Their route — Nova Scotia, Newfoundland, the Azores and Lisbon, Portugal — required several stops and ocean landings along the way for refueling and maintenance. Of the three seaplanes, only NC-4 made it all the way.

The planes flew at an altitude of about 3,400 feet and at a maximum speed of 85 mph. They were powered by four Ford-built, Liberty V-12 engines.

Martin, 69, of Gibsonia, said Rhoads was responsible for those engines, each one capable of 400 horsepower.

“He had to do a lot of rebuilding and repair work during the flight to keep those engines running. His responsibility was to keep that plane running and in the air,” Martin said.

An account written on the 50th anniversary of the NC-4 flight noted the transatlantic voyage was fraught with hazards and potential pitfalls.

“The NCs had to stay on course all night and, as it turned out, in poor weather in order not to miss the Azores,” Navy Vice Adm. Thomas F. Connolly said at the 50th anniversary celebration in Washington, D.C. “Islands can be hard to find without radio aids to navigation and radar, even islands as large as those in the Azores. It was a precision task, one that required accurate calculations and performance. Without it, failure or worse … was certain.”

Connolly said he could envision Rhoads and his fellow engineer, Lt. James L. Breese, peering from the afterhatch at the engines.

“I can picture Rhoads, wearing a safety harness, climbing out on the wing from time to time to make adjustments on his engines in flight. These two men were all-important to the NC-4,” he said.

All told, the six-man crew spent 51 hours and 31 minutes in the air, flying from Long Island to Lisbon in 19 days, Connolly said. They reached their final destination, Plymouth, England, on May 31, 1919.

Of the two surviving members of the NC-4 crew in 1969, only Rhoads attended the 50th anniversary celebration in D.C. After a career in the Navy, he became a test pilot for Lockheed in Los Angeles, Martin said.

The Smithsonian Institution restored the NC-4 in time for the 50th anniversary celebration and put it on display on the National Mall. Coverage of the 50th anniversary in Naval Aviation News showed an aging Rhoads reminiscing with fellow chief machinist Clarence Kesler, who served in the NC-1.

The NC-4 seaplane currently is on long-term loan to the National Naval Aviation Museum in Pensacola, Fla.

An airport in Somerset County was dedicated as Eugene S. Rhoads Field in 1929 but no longer exists, Martin said.

“There’s a Walmart on that site now,” he said.

The main centennial celebration will be held at 9:30 a.m. Wednesday at the old Rockaway Coast Guard Station/Riis Landing. An art exhibit commemorating the anniversary is on display at the Rockaway Artists Alliance through June 2.