Story by BRIAN C. RITTMEYER and JULIA MARUCA

Oct. 29, 2023

• Staffing shortages leave nursing homes overwhelmed, patients vulnerable, experts say

• List of nursing homes cited for abuse can be incomplete, arbitrary, experts say

• Nursing home rating system criticized over reliability, accuracy

An employee at a Westmoreland County nursing home says the conditions of her job have brought her to tears.

Residents regularly have to wait for help and often go hungry because of a lack of people to feed them. A single staffer sometimes is asked to care for 60 residents overnight.

“So many residents sit there and stare at their food,” said the woman, a nursing assistant for 20 years who asked that her name not be used used for fear of retaliation. “Some of them might wait 20 or 30 minutes until someone starts feeding them. Then they have to hope the staff member feeding them is courteous enough to warm their food.”

Industry experts agree Pennsylvania’s nursing homes are facing disastrous staffing struggles that stand to worsen, in part, because of the state’s aging population.

“There are days I thought about quitting,” the worker said. “It’s such a terrible feeling when you go into work, you give them 110%, and the patients are yelling at you that you’re doing a terrible job because they had to wait. It hurts, and I take that personally. If somebody falls because you don’t have enough help, I take that home with me.”

Pennsylvania has the nation’s ninth-oldest population, with 19% of its residents 65 or older, according to U.S. Census figures. With that population segment growing, the state’s overtaxed nursing homes are being pushed to refuse more and more patients.

“We are now seeing nursing homes forced to close their doors to new admissions simply because they don’t have enough staff,” said Zachary Shamberg, president and CEO of the Pennsylvania Health Care Association.

Nineteen facilities in the state have closed completely since the start of the covid-19 pandemic, according to state health department records.

At the Reformed Presbyterian Home on Pittsburgh’s North Side, Executive Director Cara Todhunter said only one licensed practical nurse applied for a job in six months even though the facility has increased its pay rates.

The home utilizes all of its 58 beds, but staffing shortages take a toll.

It’s a situation exacerbated by the pandemic, studies indicate.

Of the nation’s roughly 5.2 million registered nurses, 100,000 are estimated to have left their jobs because of the stress of the pandemic, a recent study by the National Council of State Boards of Nursing indicated.

Another 610,000 nurses with more than 10 years of experience and an average age of 57 said they plan to leave by 2027 because of job stress or retirement, the study showed.

Wages and working conditions continue to be an issue for long-term health care workers.

Registered nurses working in medical/surgical hospitals earn a median hourly wage of $45.56, while those at nursing homes earn $37.11, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Certified nursing assistants in hospitals earn a median rate of $18.18 per hour, while those at nursing homes earn $16 per hour.

“Nursing home work is dangerous and more dangerous if there is not enough staff to do the job and do it well,” said Matthew Yarnell, president of SEIU Healthcare Pennsylvania, the union representing health care workers from hospitals, nursing homes, state agencies and home care settings.

Some say the growth of private-equity ownership versus nonprofit control has resulted in some nursing homes valuing profit over quality of care by hiring fewer employees and keeping pay low.

For some of those facilities, “the only way they can create profit for themselves is by controlling the cost, and the major cost of any nursing home is labor,” said Michael Collis, an attorney with the Pittsburgh office of Murray, Stone and Wilson law firm. “They don’t have enough staff because that’s the way they want to be.”

But Shamberg said many of these facilities operate on slim profit margins — an average of 2.5% before the pandemic to a loss of minus 4.4% during it.

“The argument that for-profit nursing homes are just after money is flawed,” he said.

About 5% of the nation’s nursing homes are operated by private-equity groups, according to the American Health Care Association.

Many nursing home operators say low government reimbursements make it difficult for facilities to break even. According to Shamberg’s group, more than 70% of Pennsylvania nursing home residents use Medicaid to cover their stays. An increase in Medicaid reimbursements last year did not keep pace with rising costs, Shamberg said.

While a resident’s average daily cost is about $282 per day, Medicaid reimbursements are about $234, according to Eric Heisler, spokesman for Shamberg’s group.

“With about 50,000 residents on Medicaid, multiplied by 365 days in the year, you can see how that can financially harm providers,” Heisler said.

Heisler said stimulus funds offered during the pandemic helped, but those funds were a one-time offering.

Without those stimulus funds, operating margins at Pennsylvania nursing homes averaged about minus 8.2% in 2021, he said.

Insufficient Medicaid reimbursements, stricter state and federal staffing mandates, and government requirements dictating how much of a facility’s total costs must be dedicated to patient care have forced “more and more providers like the family-owned and operated providers” to sell or close, Heisler said.

“While there is a severe financial strain on providers who continue to operate, the question really becomes how much longer can they keep going?” he added.

“We don’t have the income to match what we need to do in wages, to recruit and retain staff,” said Matthew Tack, administrator of Platinum Ridge Center for Rehabilitation and Healing in Brackenridge, whose family owns a number of facilities throughout the region. “We’re very reliant on the medical assistance monies. They did increase it recently. That’s the first time in six years.

“We need more.”

New state staffing ratios requiring a minimum number of staff per resident took effect July 1.

“Honestly, (the owners) don’t care,” said the Westmoreland County staffer who wished to remain unidentified. “What happens if they don’t meet the requirements for staffing ratio? They get fined. They’d rather pay the fine.”

With 60 patients on her overnight shifts, she said she can’t give them all they deserve.

“The owner said it’s doable because they’re all sleeping,” she said. “What if there is a fire or an emergency? I can’t get people out in a timely manner.”

Last month, the Biden administration proposed staffing standards for nursing homes with a minimum of about three nurse staffing hours per resident per day.

The plan drew immediate criticism.

“It requires nursing homes to hire tens of thousands of nurses that are simply not there,” said Mark Parkinson, American Health Care Association president and CEO. “Nursing homes are facing the worst labor shortage in our sector’s history, and seniors’ access to care is under threat. This unfunded mandate, which will cost billions of dollars each year, will worsen this growing crisis.”

But the SEIU’s Yarnell praised the plan.

“People are not going to go back into (these) settings and asked to care for too many and not be paid for the valuable work they are doing,” he said.

Many facilities have turned to health care staffing agencies — which often pay considerably higher wages — to fill vacancies.

But the practice has drawn fire.

“They are not full-time employees with real ties to that facility or in many cases that community,” Shamberg said.

Despite laws requiring background checks, agency employees have been in the news lately, including one worker charged with prying the rings off the fingers of an elderly resident at Redstone Highlands in Murrysville.

At the time of her arrest, the suspect was wanted on felony counts of burglary, theft and receiving stolen property. She also was the subject of a federal indictment accusing her of stealing mail while working for the U.S. Postal Service.

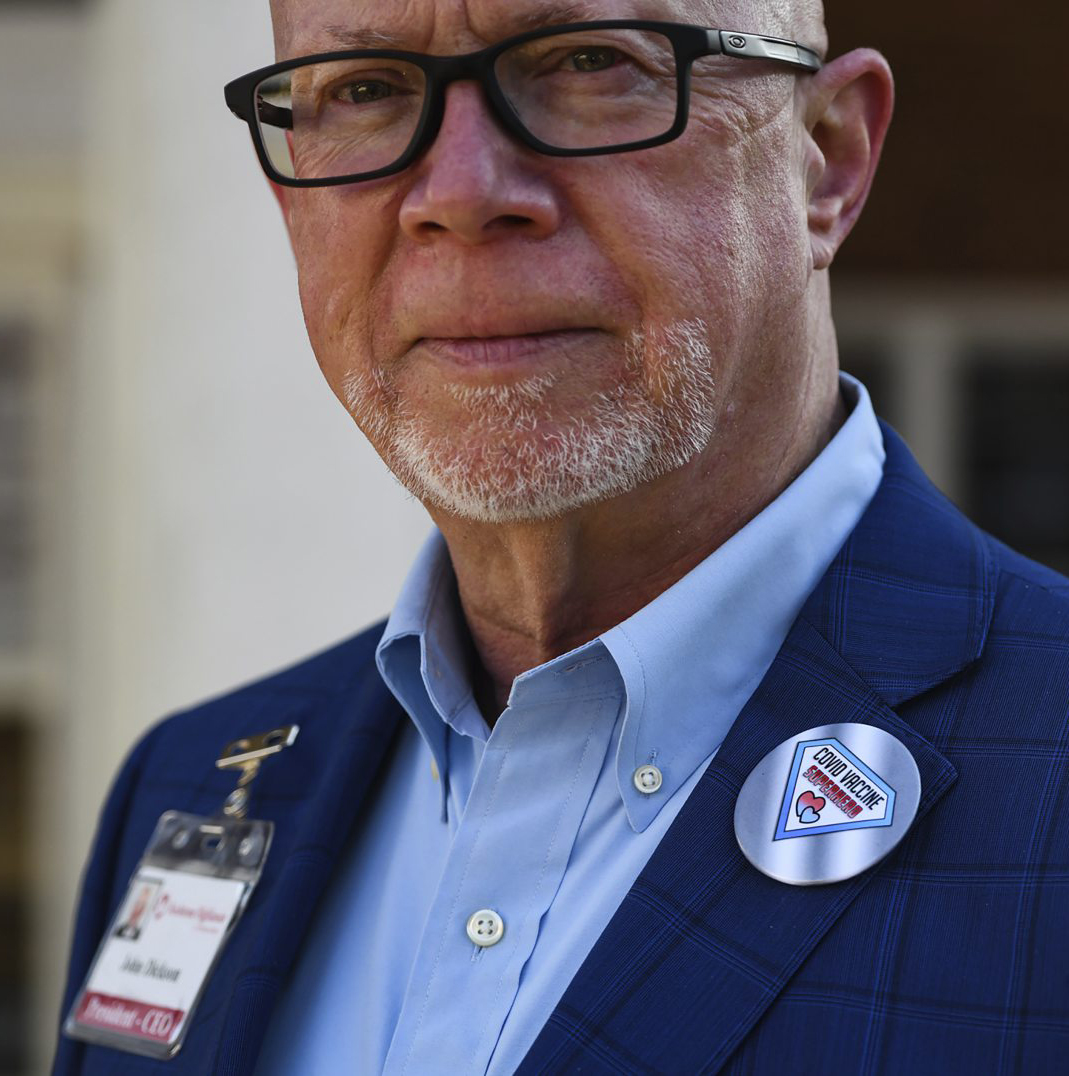

John Dickson, president and CEO of Redstone Presbyterian SeniorCare, which oversees Redstone Highlands, said he continues to work on policy changes with the agency — Dedicated Nursing Associates — that provided the worker.

“The staffing agency did their due diligence in regards to doing a background check. What happens with background checks is there are no charges ever listed, only convictions,” Dickson said. “We need a better system in order to do background checks.”

Brian C. Rittmeyer and Julia Maruca are Tribune-Review staff writers. You can contact Brian at brittmeyer@triblive.com and Julia at jmaruca@triblive.com.