Western Pennsylvania over the span of nearly a quarter century has twice found itself at center stage of national outrage involving the deaths of black men at the hands of white police officers.

The 1995 death of Jonny Gammage in the era of Rodney King and the L.A. riots focused national attention on the region. Such public ire was not seen again locally at the same level until last summer’s death of Antwon Rose II, which came on the heels of similar high-profile cases in Ferguson, Mo.; Sacramento, Calif.; and Baton Rouge, La.

Three police officers charged in the Gammage case walked free after jury trials.

More than two decades later, expectations for justice are high as former East Pittsburgh police officer Michael Rosfeld heads to trial, charged with criminal homicide for shooting and killing Rose, 17, on June 19.

Rose was among 998 Americans — both black and white — who died last year after being shot by police.

Rosfeld is among a much smaller group. He is one of just 98 police officers charged with murder or manslaughter in such deaths over the last 14 years.

Philip Stinson, a former police officer and attorney, is a Bowling Green State University criminology professor who has tracked those numbers since 2005. During that period, he said about 900 to 1,000 people died every year of gunshot wounds from on-duty police officers.

While charges against officers in such shootings are rare, convictions are even rarer. Of the 98 officers charged, three were convicted of murder; 32 others were found guilty of manslaughter or lesser crimes.

On one level, Stinson said when charges are filed and a case goes to trial, justice is done regardless of the outcome. But even the former policeman hesitates to say all involved will feel that way.

“Many would say justice has not been done where there is not a conviction,” Stinson said. “You have victims and family members who live in these communities, and they are very concerned about these issues. It is perfectly reasonable for them to feel justice has not been done.”

Little appears to have changed in the criminal justice system over the last 14 years, Stinson said.

“I think people are paying more attention to it. It is national and international news these days instead of just a local story,” he said. “We see little increase in the number of officers charged, but I think prosecutors are under pressure to make sure investigations are conducted and that now they often have to explain their rationale when they don’t charge.”

This month, state and local authorities declined to prosecute two Sacramento, Calif., police officers involved in the March 2018 shooting death of a 22-year-old black man. Federal authorities have since said they will conduct an independent civil rights investigation.

State and local authorities concluded the officers were justified when they shot Stephon Clark seven times as he ran through his grandmother’s backyard holding a cellphone after smashing windows on several parked cars and throwing a cement block through a neighbor’s glass door.

Eroded trust

Countless videos showing unarmed black men dying at the hands of police have left a mark, said Karlos Hill, a history professor who chairs the department of African and African American studies at the University of Oklahoma.

“It’s absolutely the reason we have a Black Lives Matter movement,” Hill said.

Police shootings and excessive use of force further erode the historically less-than-trustful relationship between the black community and law enforcement when no one is held to account, Hill said.

An East Pittsburgh resident captured a cellphone video of Rosfeld shooting Rose as the teen ran away. The video went viral on social media, sparked days of protests and shouts of “Justice for Antwon Rose,” as protesters closed first the streets of East Pittsburgh and then the Parkway East.

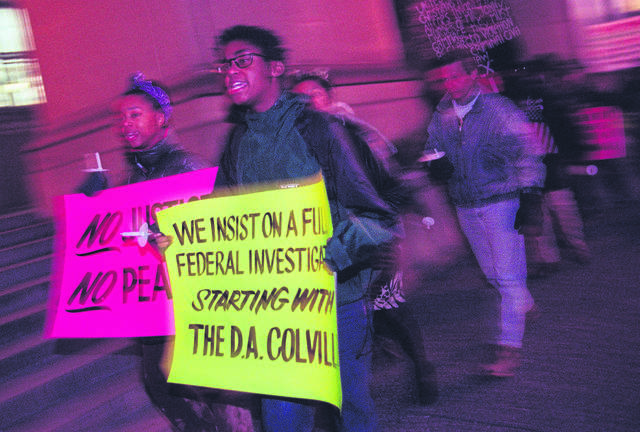

No such video existed of Gammage’s death. Nonetheless, it sparked protests and demands for justice for the young black businessman.

Tim Stevens, a longtime Pittsburgh civil rights activist, in 1995 served as president of the local NAACP. He joined local ACLU officials to lead peaceful protests, which saw hundreds of marchers silently circle the Allegheny County Courthouse and the City-County Building in Pittsburgh to protest Gammage’s death.

“It was profound,” said Stevens, now CEO of the Pittsburgh-based Black Political Empowerment Project, or B-PEP.

Pittsburghers filed complaints of police brutality that led to the Police Citizens Review Board being created and a five-year consent decree in which the federal government had oversight over city police.

It also led to the creation of a Pittsburgh Black and White Reunion. Stevens said the group, today known as the Racial Justice Summit, advocates for racial justice.

Some believe the only justice received by blacks who die at the hands of police comes through civil lawsuits rather than criminal proceedings, Hill said.

That was route the family of Michael Ellerbee took when authorities declined to file charges against a Pennsylvania State Police trooper who shot the 11-year-old black child from Uniontown, Fayette County, on Christmas Eve 2002.

Trooper Samuel Nassan shot and killed Ellerbee as he ran from a stolen SUV after leading police on a chase.

A jury in 2008 awarded Ellerbee’s family a record $28 million in a federal civil rights suit. The sum was reduced when state police agreed to drop their appeals and pay $12.5 million a few months later.

“We as a society have substituted payouts for real accountability,” Hill said.

Last summer, it took authorities six days to file charges against Michael Rosfeld. It took three months for charges to be filed against police officers involved in Gammage’s death.

Gammage, 31, died after Brentwood police stopped him just over the line in the city of Pittsburgh after noticing him braking frequently as he drove a Jaguar through the borough. The car belonged to his cousin, Pittsburgh Steelers defensive end Ray Seals.

Police officers from Brentwood, Baldwin and Whitehall tackled Gammage, handcuffed and pinned him on the ground in an attempt to subdue him. Gammage died of suffocation.

Authorities charged three officers with voluntary manslaughter. One officer was acquitted at trial. Charges against two others were dropped after two mistrials.

Monroeville defense lawyer Patrick Thomassey, who represented Brentwood police Lt. Milton Mulholland through two mistrials in the Gammage case, is representing Rosfeld more than two decades later.

Unlike Mulholland, Rosfeld has been charged with criminal homicide in Rose’s death. The count holds possible outcomes ranging from first-degree murder to involuntary manslaughter.

Changing the system

Stevens said the severity of the charge indicates Allegheny County District Attorney Stephen Zappala is taking such issues seriously.

But national statistics that show how few officers were ever charged in the thousands of police shootings over the last 14 years are “beyond troubling,” Stevens said.

The Antwon Rose case suggests a critical need for regional police forces and better training, Stevens said. Rose was shot and killed hours after Rosfeld was sworn in as part of the tiny East Pittsburgh Police Department, which has since disbanded.

He said his group has submitted a 35-page recommendation to authorities asking, among other things, that small police departments request training from the Pittsburgh Bureau of Police — one of six departments across the country trained in recognizing implicit racial bias under an Obama administration initiative. Stevens was optimistic that those recommendations have been well received.

Whether they can head off future deaths is another question.

James Nolan, a professor of sociology and anthropology at West Virginia University and a former FBI agent, said the high number of police shootings across the country every year reflects a deeper issue.

“The culture of American policing leads to broken trust with the community and the development in officers of a disposition that is overly suspicious, hyper-vigilant and overly fixated on ‘making it home safely’ at all costs,” Nolan said. “Shifting measures of success from law enforcement outputs such as number of arrests and drug and gun seizures to safe, strong community outcomes would change the disposition and logic of officers doing policing work.”