On most days, uniformed Pittsburgh police officers work off-duty gigs across the city.

These side jobs are supposed to be a win-win-win arrangement: Businesses pay for a highly trained and visible police presence to provide security or direct traffic; officers looking for extra cash enjoy a lucrative side hustle; and the City of Pittsburgh, which authorizes the work, earns fees from the employers.

But under outgoing Mayor Ed Gainey, the city has been the biggest loser.

A TribLive investigation turned up city records showing hundreds of businesses and organizations — from a strip club to a soup kitchen, from restaurants to bars, from Duquesne Light to the Catholic Diocese of Pittsburgh — enjoyed years of police services and millions of dollars of work without paying a cent.

After Gainey took office in 2022, the employers’ debt mounted, peaking last year at $3 million spread among 200 or so employers, financial records reviewed by TribLive show.

In June 2021, under former mayor Bill Peduto, unpaid invoices for police moonlighting totaled less than $200,000, the records show.

Meanwhile, the Gainey administration did little to collect on the unpaid bills.

Internal memos, interviews and public records reveal a multimillion-dollar moonlighting program that has been hobbled by shoddy recordkeeping, anemic collections efforts and minimal oversight.

This organizational disarray has festered more than a decade after oversight of the secondary employment program was supposed to be tightened following the arrest and prosecution of Nate Harper, the former Pittsburgh police chief who was ousted and went to federal prison for misusing the city’s moonlighting funds.

“This is simple bookkeeping — or it should be,” said City Councilman Anthony Coghill, D-Beechview, chair of the public safety committee. “But nobody knows what’s going on.”

The public safety department’s management of the program — specifically its disjointed efforts to get businesses to pay for services rendered — has become what Elizabeth Pittinger, the longtime executive director of Pittsburgh’s Citizen Police Review Board, called a “free-for-all.”

Pittinger believes poor supervision and a rotating cast of police chiefs under Gainey set the stage for the current financial mess.

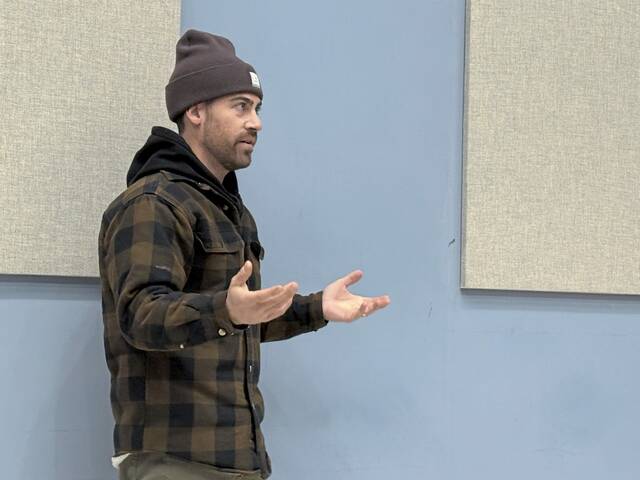

Robert Swartzwelder, the police union leader, had harsher words.

“You’re either blatantly incompetent or there’s some level of corruption there,” Swartzwelder said. “Which is it? You pick.”

Recent progress

As some employers’ bills went unpaid, the city was forced to use moonlighting fees it had collected to cover the wages of the police officers who worked the side jobs. Officers can earn time-and-a-half or more while moonlighting. The city tacks on an hourly fee of $6.56.

Pittsburgh essentially used money from businesses that paid their bills on time to subsidize those listed as deadbeats.

In almost all cases, Pittsburgh kept supplying moonlighting officers to employers listed in city records with chronic unpaid bills.

Only in recent months has Pittsburgh ramped up collection efforts. In September, it signed a new five-year contract to pay up to $85,000 to RollKall, the technology firm that has helped run the secondary employment program since 2022.

In late November, unpaid moonlighting invoices still hovered around $1 million, according to records reviewed by TribLive.

That’s roughly the same amount the city charges employers each month through the secondary employment program to cover fees and the moonlighting wages paid to police officers.

Half of the program’s bills that are marked as unpaid have been delinquent for more than 120 days, according to the city.

For months, Gainey has declined repeated interview requests from TribLive about the arrears.

In a prepared statement, the mayor said collecting unpaid bills has “long been a challenge,” citing turnover among staff managing the program.

Now, though, RollKall will cover any delinquent costs and handle collections.

“Our team is now working to transition responsibility for managing invoices for the program to the vendor that also handles the scheduling process,” Gainey said. “This will ensure the city is paid up front, while the vendor takes responsibility for collections.”

Top city officials acknowledged the lack of a clear strategy to dun employers for past-due bills. They blamed the chaos on staffing turnover and outdated software.

Some businesses said they sent payments to the city only to have their checks go uncashed.

Gainey officials, including the mayor’s top lieutenant, Jake Pawlak, argued the amount owed is minuscule compared with Pittsburgh’s $666 million budget and represents less than 3% of all hours worked by moonlighting officers since 2022.

No taxpayer funds, they said, have been used to make the moonlighting officers whole.

Hoping they pay

The business with the biggest debt to the city is Cheerleaders Gentlemen’s Club on Liberty Avenue in the Strip District.

As of late November, according to city records, Cheerleaders had 21 unpaid bills for $105,406.79, some dating to 2022.

Management at the strip club did not respond to multiple phone calls, emails or in-person visits to their establishment seeking comment.

City records showed earlier this fall that PNC Bank owed more than $58,000, Rivers Casino racked up a $57,000 debt and Peoples Gas failed to pay about $18,500.

Peoples and the casino told TribLive their moonlighting tabs had been paid recently. PNC didn’t return emails or phone calls seeking comment. This summer, some businesses told TribLive they were never notified about the debts.

Pittsburgh officials acknowledged the city’s accounting system might not have properly reconciled when businesses paid their bills or had their debts forgiven.

Garfield Jubilee Association, a nonprofit that develops programs to “stabilize the welfare of low- and moderate-income families,” had the second-largest outstanding bill at $83,871.06, recent RollKall records show. A total of 22 of their invoices remain unpaid.

The association declined to talk with TribLive.

The city’s experience with BURN by Rocky Patel, a cigar club on the North Shore, illustrates problems with the shambolic collections system. The company, headquartered in Naples, Fla., hired Pittsburgh police officers for security.

On June 7, 2022, Pittsburgh billed BURN for more than $6,000. The city said BURN didn’t pay. Top officials in the Gainey administration said they did not know when — or if — a follow-up invoice was sent.

Neither the city nor BURN would provide TribLive with invoices or any related correspondence.

In the meantime, the city kept sending police officers to BURN — and churning out invoices.

In July 2022, the city charged $4,405.62. Another bill totaled nearly $3,000. The debt kept rising, according to city records. By the end of 2023, the club owed more than $28,000, city records show.

City officials only recently inquired about past-due bills, Robin Sarro, an accountant for the company, told TribLive in June.

“And we’ve paid all of it,” Sarro claimed.

“We had no idea there were outstanding invoices with the Pittsburgh PD — I really do not think they did, either,” added Mike Howe, the company’s director of operations. “BURN by Rocky Patel is a very well-known national brand and not too hard to contact in some form or fashion.”

Pawlak, the director of Pittsburgh’s Office of Management and Budget, said there’s no central database to track when invoices were sent to BURN or any other business — of if they were sent at all.

“We send them an invoice, and hopefully they pay,” Pawlak said. “There have been some difficulties with that.”

Pawlak and Pittsburgh Public Safety Director Lee Schmidt cannot say definitively which delinquent businesses were contacted about unpaid bills or when — or whether they were even contacted.

They also could not say how many invoices were paid but not reconciled, paid to the wrong city account or were subject to clerical errors.

Some of the debt, Schmidt said, will likely be written off as public support for community events.

There is no written record, though, that tracks which events are getting free police services — or who decides what, or how much, is gratis.

William “B” Marshall’s Stop the Violence group is listed as owing the city money.

But Marshall pointed out the mayor has publicly stated the city would cover the costs of police for at least some of the group’s events. He said he does not have anything in writing to that effect.

Raising red flags

At some point — Pittsburgh officials could not say when — the city cut off moonlighting services to Cheerleaders. It later was followed by Garfield Jubilee, making them the only two vendors barred during Gainey’s tenure because of arrears.

Justin Snasel, a spokesman for RollKall, said the vendor “flagged a rising accounts receivable balance” to Pittsburgh leaders more than a year ago concerning numerous businesses.

Snasel declined to detail what RollKall told police — or what the unpaid balance was at that time.

He said the city “retained responsibility for payment collection and reconciliation.” That changed last month when RollKall took over collections for the city.

Pittsburgh police Commander Eric Baker, who helps oversee the secondary employment program, said RollKall last year issued a warning about the rising debts.

“I’m paraphrasing, but they said, ‘This is unusual. This is an unusually high amount of unpaid invoices, as our clients go,’ ” Baker recalled.

Christopher Ragland, a former acting police chief under Gainey, raised concerns about the secondary employment program in numerous internal memos among police brass. The earliest memos, which were reviewed by TribLive, were sent in 2023, when Ragland was an assistant chief under then-Chief Larry Scirotto.

In an August 2023 email, Ragland told Scirotto that growing moonlighting debts were “very troubling.” He recommended delinquent companies be cut off from being able to hire police officers for side jobs. The suggestion was never implemented.

By late 2024, nearly 18 months after the first alarms were raised, businesses still owed Pittsburgh millions of dollars for work already completed.

Baker described months of inaction by city officials handling debt collections as a disturbing pattern.

“I want someone to say, ‘Look, we’re never going to be able to collect all’ ” the unpaid invoices, Baker said.

“They should say, ‘Some of these guys are nonprofits and we don’t want to hold their feet to the fire.’ But they don’t say that,” Baker said, referring to city and public safety officials. “It’s ‘maybe.’ It’s ‘sometimes.’ You know, I’d like to do that with my own bills, if possible.”

In multiple interviews with TribLive, Schmidt and Pawlak offered few concrete answers about how the city tried to manage the program and collect overdue payments. They repeatedly cited privatizing the invoicing process with RollKall as a fix.

Schmidt blamed some of the billing problems on disruption caused by the transition from one mayor to another and turnover at the upper echelons of the police bureau.

“I think there was some lack of procedures that followed through with the loss of staff,” Schmidt said.

A question of transparency

Businesses interviewed by TribLive described an error-prone billing process.

One company claimed it mailed Pittsburgh three separate checks to pay a moonlighting tab but all of them expired after the city failed to deposit them within 90 days.

A spokeswoman for another company, Thayer Infrastructure Services, said Pittsburgh sent invoices to a person who no longer worked at the company. City records show the Ohio-based utility maintenance firm recently paid nearly $30,000 it owed for moonlighting work.

A TribLive reporter was the first to alert Thayer to the debt, she said.

In August, Schmidt told TribLive the city “sometimes” picks up part of the tab when “small community groups” hold events where security is needed.

He was unable to cite specific events or dollar amounts or even ballpark a total.

A provision in city code says Pittsburgh can forgive $750 to groups staging parades, engaged in First Amendment-related activities, or running community events and block parties in the city.

Gainey also can forgive expenses. And sometimes, as in the case of the 2026 NFL Draft, the tab is picked up by Pittsburgh through formal legislation approved by City Council. Pittsburgh, which is the host city next April, will cover $1 million as well as provide in-kind services to support the draft.

Apart from those provisions, there don’t seem to be any city rules concerning how to deal with businesses that don’t pay their bills.

Pittsburgh Controller Rachael Heisler has been reviewing program records but has not conducted a full audit.

“Between inconsistent management within the Pittsburgh Bureau of Police, inadequate follow-up for collections and poor record reconciliation, it’s easy to see why there’s minimal confidence in the program,” Heisler told TribLive.

Inaccurate figures

The city itself has handed out erroneous information.

In August, public safety officials gave TribLive a spreadsheet about the city’s secondary employment fund, which collects moonlighting fees from businesses that use the program.

It is this fund the city has tapped to pay the wages of police officers working at deadbeat businesses. It had $3.6 million in August.

The spreadsheet incorrectly indicated the fund fell into the red multiple times during Gainey’s tenure.

Days later, officials released a second spreadsheet which contradicted the first and showed the fund had never dipped to negative numbers.

The only publicly accessible details about the fund’s expenses, revenues and balance are through the city’s website and in quarterly financial reports.

The city has released three reports so far this year; two provided inaccurate dollar figures for the fund.

“At the very least, it’s choppy, crazy, messy bookwork,” said Coghill, the councilman. “Should there be a better system? Absolutely.”

No clear guardrails

Problems have plagued the secondary employment program for years.

In 2013, Harper, the former Pittsburgh police chief, pleaded guilty in federal court to charges of conspiracy and willful failure to file income tax returns.

From 2009 to 2012, Harper diverted more than $70,000 in moonlighting fees to two slush funds he ran through a police federal credit union.

He used almost $32,000 for personal expenses and failed to file federal tax returns between 2008 and 2011.

Harper got 18 months in prison.

“Systemically, since the beginning, since the big scandal — in 2012, 2013 — up until now, council and the mayor’s office, they’ve never taken the steps to draw up regulatory rules,” Michael Lamb, the city’s former controller, told TribLive this spring.

Pittsburgh continues to operate the secondary employment program without clear guardrails.

“There are a bunch of different eyes on it,” Schmidt said. “And we’re constantly working toward improvement. But change takes time.”

Alison Dagnes, a Shippensburg University political science professor who lectures on good governance, said poor management like this hurts the city’s credibility.

“Missing money and shoddy recordkeeping can erode public trust, even if there’s no intentional fraud,” Dagnes told TribLive. “Right now, when public trust in government is at an all-time low, this doesn’t help. It may not be on purpose, but even if it’s incompetence, that’s not a good look either.

“There’s no good answer,” she added. “If money is missing, then there’s never a good explanation for it – ever.”

Justin Vellucci is a TribLive staff writer. He can be reached at jvellucci@triblive.com. Julia Burdelski is a TribLive staff writer. She can be reached at jburdelski@triblive.com.