An Allegheny County bus mishap cost Joan Grove her leg. Another bus accident in Philadelphia took part of Hayley Freilich’s foot. Deadly bacteria at the old state prison in Pittsburgh killed Joseph Mollura.

How much is a leg worth? A foot? A life?

Under state law, not enough, say lawyers for those victims and their families.

They all sued state or local government agencies over the catastrophic incidents. And after settling or winning their cases, they all ran into the same problem: legal limits on how much money they could collect.

No matter how many millions of dollars a jury might award in such cases of grievous injury or death, state law protects municipalities and counties in Pennsylvania, capping payments at $500,000, even when found liable for the most horrific, life-altering incidents. The limit is even lower for the state: $250,000.

And those amounts are for the total payout, no matter how many victims.

Now, those hurt in the Fern Hollow Bridge collapse could face the same predicament if they win their pending lawsuits against the city of Pittsburgh.

The law says the eight victims of the Jan. 28, 2022, disaster who have gone to court can wring no more than $500,000 from Pittsburgh — in total, not per person.

If a maximum award were to be split evenly among the victims, each would get $62,500 for their broken bones, bruises, hospital stays and lingering mental anguish — all caused by a disaster that federal investigators blamed on lax maintenance by the city and poor state and federal oversight.

That amount wouldn’t even include lawyers’ fees and costs.

Jason Matzus, one of the Fern Hollow attorneys, called the situation “horribly unjust.”

These dollar limits — on the books and unchanged for nearly 50 years — are some of the strictest in the country, according to Tom Kline, a Philadelphia lawyer.

“There’s no state in the union that has a more draconian cap than Pennsylvania,” Kline said.

Advocates for the caps say they are necessary to protect against windfall judgments that could bankrupt a small community or governmental agency, and that buying insurance policies to protect against such cases is prohibitively expensive.

But plaintiffs’ attorneys disagree.

Kline, a Duquesne University Law School alumnus and major donor, has been fighting the caps for more than 25 years.

“Catastrophic injury and death claims are few and far between, so the bank won’t be broken,” he said.

‘Devastating’ consequences

In Pennsylvania, municipalities and state bodies enjoyed complete immunity from civil damages until the 1970s. That’s when the state Supreme Court eliminated such protection in a case involving a 15-year-old boy whose arm was caught in a shredding machine at a Philadelphia public school.

The Legislature responded by passing the Tort Claims Act in 1978, which remains in force today.

That statute set rules for when a person could sue a governmental entity — because of injuries or death from accidents involving government-owned vehicles, medical malpractice, dangerous roads and bridges, and a handful of other circumstances.

The limits on how much money can be recovered remain stuck in the past at $250,000 for Pennsylvania and $500,000 for local governments.

According to a Legislative Budget and Finance Committee report, the caps in 2022 dollars would be equivalent to just over $1 million and nearly $2.1 million, respectively.

“This cap has not been adjusted since it was enacted,” said Peter Giglione, an attorney for Daryl Luciani, the Pittsburgh Regional Transit bus driver who was caught on the Fern Hollow Bridge the day the span failed.

The dollar amounts are arbitrary, Giglione said.

“It has nothing to do with anything,” he said. “It makes no logical or economical sense.”

The legislative committee studied cap limits in response to a 2021 state Senate request. It found that more than 99% of the time, payouts were below the caps.

But in the remaining 1% of cases?

“For plaintiffs who have been catastrophically injured by governmental entities subject to the caps, the caps are inadequate and have devastating health and financial consequences,” the report said.

‘Completely inadequate’

Joseph Mollura was the medical director at the State Correctional Institution at Pittsburgh in 2016 when he became ill with Legionnaires’ disease and died.

According to court filings, testing in a cooling tower that served the medical unit showed the water system was “infested” with Legionella bacteria and that those results had been reported to the state Department of Corrections.

In 2017, Mollura’s widow sued the corrections department in Allegheny County Common Pleas Court. She alleged the state agency failed to take appropriate action, leading to the doctor’s death at age 60. The couple, who had been married for 34 years and had four adult children, lived in McKeesport.

The case against the corrections department settled, according to court filings, for $475,000 — just under the cap and well below the $2 million in lost earnings that an economist had calculated Mollura would have made during another 10 years of work.

Attorney Andrew Rothey represented the Mollura family. He said the damage caps make cases like the Molluras’ cost prohibitive given the expense of litigation, which involves expert reports, depositions and going to trial.

“Someone has to bear the cost of wrongful conduct that leads to catastrophic harm or death,” Rothey said. “Those costs are now being borne by injured individuals and their families.”

Joseph Froetschel represented Joan Grove, who was run over by a bus in Downtown Pittsburgh on June 6, 2014.

Her right leg was amputated below the knee, and her right thigh was degloved, according to a lawsuit she filed against the Port Authority of Allegheny County, now Pittsburgh Regional Transit.

Grove later developed a MRSA infection and required extensive skin grafts.

The case went before a jury, which awarded damages of $2.73 million. Because the jurors found that Grove was 50% responsible for what happened, the award was cut in half.

But that amount was knocked down once again because of the cap. Suddenly, a seven-figure award became $250,000.

Grove deserved more, Froetschel said. She lost her leg and spent months in the hospital. His client will have lifelong medical bills and must deal with the ramifications of losing a leg.

Caps leave no incentive for government lawyers to settle, Froetschel said. If they lose at trial, there’s no risk of having to pay more than the legal maximum.

In Grove’s case, he said he went to trial simply to do right by his client.

“The jury correctly recognized that all of this is millions of dollars, so it is completely inadequate to cap her damages to $250,000,” Froetschel said.

Protecting taxpayers

In the last 10 years, neither the City of Pittsburgh nor Allegheny County has paid a claim at the statutory cap.

Pittsburgh Regional Transit has paid three such claims — including for Grove’s injuries and two separate pedestrian fatalities, according to spokesman Adam Brandolph. The family of Barbara Como, a University of Pittsburgh student who was struck and killed by a bus in Oakland on Jan. 18, 2020, settled with the transit agency in 2022.

And the family of Dal Maya Rai, 64, of Whitehall, settled in February for $250,000. Rai was struck by a bus at Liberty and Sixth avenues on Jan. 11, 2022, and died two days later.

A spokesman for the transit agency would not comment on the caps.

City of Pittsburgh Solicitor Krysia Kubiak said the city supports them.

“The cap protects taxpayers from a potential abuse of the legal system and the threat of excessive damages causing settlements or judgments that deplete public resources,” Kubiak said in a written response to questions.

Kubiak said that by paying the cap amount, the city can “make the victims whole” and spare taxpayers the additional costs of going to trial.

“The cap helps bring reality checks to all of the attorneys involved for both sides, while giving the city a much-needed tool to help protect taxpayers’ funds and make sure that the city can continue to operate in the best interests of its residents,” she said.

That the city has not paid a case to the cap in 10 years shows that it is adequate, she said.

Raising, or eliminating it, Kubiak said, would risk drawing money away from city maintenance and services.

The state committee report did not give specific breakdowns for the total number of claims paid at the cap by state or local government agencies.

Ira Weiss is the solicitor for Pittsburgh Public Schools and has worked in municipal law for 50 years. He never has had a client who had to pay out to the cap maximum. But he, too, supports the law that established it.

“The damage cap is a recognition that any judgment against a public body comes out of the taxpayers’ pocket,” he said. “The legislature tried to create a balance between trying to provide people a remedy and protect the public from excessive awards from municipalities that can’t afford it.”

Relief in sight?

Attorneys who have been fighting the caps claim they are unconstitutional.

They say victims who are injured by a public entity are treated differently than those hurt by a private business. They also argue that the limits impinge on a person’s right to a trial by jury and violate the right to due process.

Kline, the Philadelphia lawyer, said he has been fighting the caps since 1996, when he had a case involving a boy who lost his foot in an escalator owned by Philadelphia’s regional transit system.

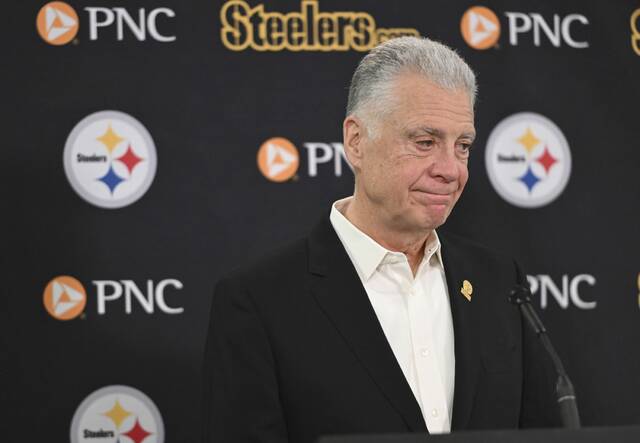

Kline

Harrisburg solution?

Giglione, the lawyer in the Fern Hollow case, thinks the high court is the best place to seek relief. One stumbling block, he said: The caps affect only a small number of people.

“I don’t think the legislature is facing enough pressure to do it,” he said.

State Rep. Emily Kinkead, D-Brighton Heights, who is also a lawyer, is contemplating introducing a bill to change the statute. Last summer, she circulated a co-sponsorship memo on the issue, specifically citing the Freilich case as her motivation.

“This is a horribly egregious case but far from the only instance of this law standing in the way of adequate justice,” she wrote.

She also noted that her memo was partly prompted by Fern Hollow.

“There should be a way for those people to get a reasonable amount of money,” Kinkead told TribLive. “This government actor was so negligent, and the harm so significant, there needs to be more accountability and sort of a deterrent. We need to take this seriously.”

Her proposal would increase the cap and include an exception if the defendant admits liability and agrees to pay more.

There’s no incentive, she said, for government entities to do better.

At the same time, she said, a balance needs to be struck with smaller transit agencies and municipalities that are concerned that higher caps could bankrupt them.

Alan Blahovec, the executive director of the Westmoreland County Transit Authority, said the agency has not paid any claim out to the cap and deemed the limit critical to organizations like his.

“Without the caps many small transit agencies will likely not be able to obtain coverage at all or coverage costs will increase exponentially resulting in service cuts,” he said. “(T)he impact to municipal government in altering or eliminating the cap would leave people stranded without life-sustaining mobility options.”

Role of insurance

Giglione said that when the caps passed in 1978, the Legislature was likely trying to minimize the impact on taxpayers.

That’s why there’s insurance, he said.

But Weiss said many local governments and agencies, including the school district, City of Pittsburgh and Pittsburgh Regional Transit, are self-insured because of exorbitant insurance costs. That means that any payments in court cases are made from the government’s own treasury.

Kline dismissed longstanding arguments by local governments that eliminating caps would lead to a flood of expensive claims.

He noted that the cap doesn’t apply to federal civil rights claims such as the recent settlement involving Pittsburgh and the family of Jim Rogers, a homeless man who died a day after a city police officer shocked him multiple times with a Taser. The city paid $8 million — and didn’t go bankrupt.

Pennsylvania is hardly alone in capping payouts by local and state governments. More than half the states have such limits, according to the legislative report.

But the commonwealth’s neighbors, Ohio and West Virginia, don’t cap economic damages such as medical bills and lost wages — and New York State has no caps at all.

So if a bridge were to fail across the state line, victims might have more luck in court there than they would in Pennsylvania.

But lawyers like Matzus, whose client, Clinton Runco, broke his neck and sternum in the Fern Hollow collapse and suffered blood clots in his lungs, must face the fact that their disaster happened here.

Giglione’s client, Luciani, the bus driver, suffered a severe shoulder injury that remains painful. He still has nightmares and post-traumatic stress disorder from the bridge failing as he drove across it with two passengers.

As the two-year time frame to file suit ticked down, Giglione, Matzus and the other attorneys on the case worked frantically to determine whether any private entities who inspected or worked on the bridge might be liable, too.

They’ve named two additional engineering firms as defendants. If found liable, they would not be subject to the damages cap, the attorneys said.

The state-mandated cap is bad enough, according to Giglione. What’s worse, he said, is the law that spreads a potential payout of $500,000 among all the victims.

“For one person, that might be a little easier to swallow,” Giglione said. “If 20 people had died on that bridge, their families are splitting $500,000.”