A comprehensive study on racial disparity in Allegheny County’s criminal justice system shows that Black people are five times more likely to be arrested than white people, 10 times more likely to be held in jail while awaiting trial and nine times more likely to be convicted of a felony.

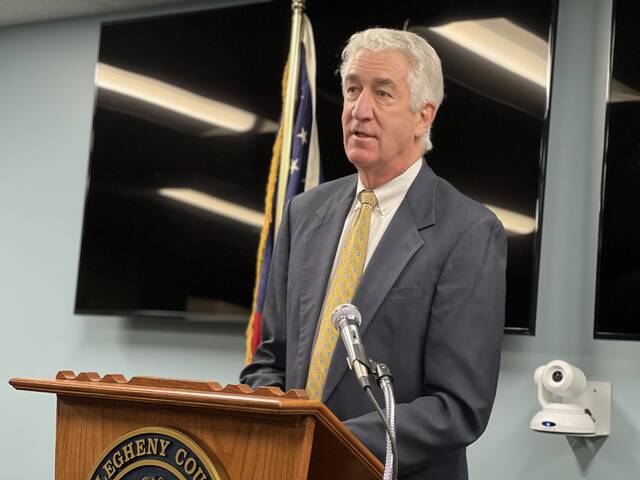

Former U.S. Attorney Fred Thieman, a co-chair for the University of Pittsburgh’s Institute of Politics, called the findings disturbing.

“These problems need to be solved,” he said. “They need to be addressed, but the criminal justice system can’t solve all of them.”

Education, poverty levels and lack of opportunity all contribute to issues of race disparity, Thieman said.

The results of the 248-page study, conducted by Rand Corporation and RTI International, were announced Tuesday morning at a news conference hosted by County Executive Rich Fitzgerald.

Thieman called the report complicated and nuanced, just like the criminal justice system. The study was commissioned by the Institute of Politics, and work began on it eight years ago.

The report looked at four areas of the criminal justice process: policing, pretrial detention, criminal court and probation.

The data it used stemmed from arrests made between 2017 and 2019. During that time, 88,511 new criminal charges were filed, the study found.

The report found that certain neighborhoods are more heavily policed, and the greatest racial disparity in charges being filed against Black and white people is in the suburbs where more white people live.

It also found that Black people are more likely to be arrested than charged by citation or summons, and Black people are more likely to be held without bail or to have cash bail set.

Black people also are more likely to be convicted of a felony and more likely to be sentenced to incarceration, while they also receive minimum sentences that are 5.4 months longer than white people, the report found.

“We didn’t need a report to tell us what we as organizers have said for three years,” said Miracle Jones, the director of policy and advocacy of 1Hood Media.

Still, Jones continued, the report shows there are things law enforcement, the courts and prosecutors can do immediately to reduce racial disparity.

“If people just had the political will to do so, the incarceration rate at the jail wouldn’t be so high and the disparity rate wouldn’t be so high,” she said.

Jones said the report gives legitimacy to the problem of racial disparity for those in the community who haven’t been listening to advocates for reform.

“They should now be ready to implement these recommendations,” she said. “We don’t need another working group. What we need now is action.”

Allegheny County President Judge Kim Berkeley Clark said court officials will evaluate the report’s findings.

“In so doing, the court must also consider the potential impact of the recommendations on community safety and victims of crime, something the report acknowledges was not within the scope of the study.”

Clark said the study found that judges in Allegheny County are sentencing in accordance with state guidelines.

The court has worked for years to make criminal justice as fair and equitable as possible.

She cited several efforts already in place, including the use of risk-assessment tools in determining whether a person should be released prior to trial and the sustained reduction in the jail population of 15% since the pandemic.

The court system shared data with the Institute of Politics for the study, made staff available for interviews and participated in meetings, she said.

“Eliminating racial disparity in the criminal justice system can only be accomplished if Allegheny County as a community solves the socioeconomic problems that inundate the criminal justice system with racially disparate numbers,” Clark said.

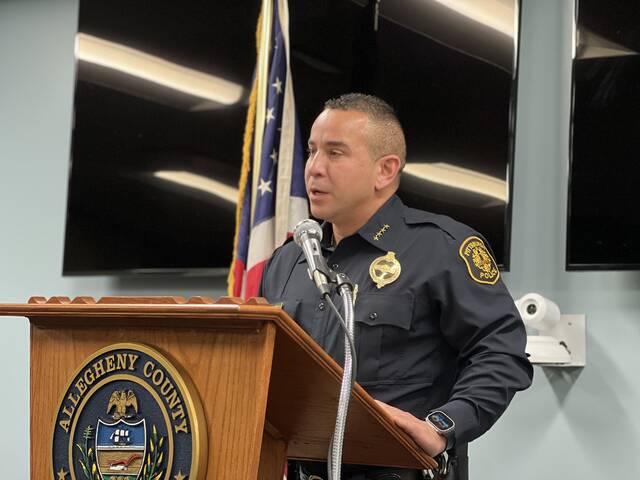

Pittsburgh police Chief Larry Scirotto, who has been in office since June, was open to the report’s findings.

“As the second-largest police department in the commonwealth, I think it’s critically important for us to be leaders in developing responsible policing strategies that mitigate harm in our communities, especially in our communities of color,” he said.

Scirotto acknowledged that policing strategies are different in Black neighborhoods.

“The Pittsburgh Bureau of Police acknowledges the importance of understanding these factors and is dedicated to addressing any disparities that may arise from this style of policing,” he said.

Scirotto said that some of the study’s recommendations merit serious consideration — including reducing pretextual stops, which he called “fishing expeditions.”

He said he also hopes to expand the department’s partnership with the district attorney’s office to consider the use of civil citations for minor violations.

Allegheny County District Attorney Stephen A. Zappala Jr. did not respond to a request for comment on the report. He did not attend Tuesday’s news conference. No one from the court system was present either.

The report includes anecdotes from researchers’ interviews with members of the community and people who work in the criminal justice system.

Broadly, the study reported that those interviewed described Allegheny County as highly segregated by race and class, “reflecting a long history of social and economic discrimination against Black residents. In particular, they noted that predominately Black neighborhoods have been systematically excluded from public and private resources, leading to concentrated poverty and crime.”

Those interviewed told researchers that Allegheny County feels fractured — as if each neighborhood has its own justice system and “people with virtually identical backgrounds except for race can experience vastly different justice in Allegheny County.”

The study said that people in Black communities are accustomed to intensified policing and surveillance practices.

“Rather than promoting feelings of public safety and trust in criminal justice authorities, feeling constantly watched by the police and being frequently subjected to pretextual stops that they know could escalate to an arrest or worse erodes Black residents’ goodwill toward law enforcement,” the report said.

Researchers noted some limitations in the study. They included having to rely on data from 2017 to 2019 given that there have been “some significant policy changes since then.” However, using the data from that time period was necessary because of the covid-19 pandemic, it said.

Researchers said they also weren’t able to obtain much data from suburban law enforcement agencies. In some instances, the study said, it was difficult to conclusively identify whether disparate treatment occurs because of race or some other factor.

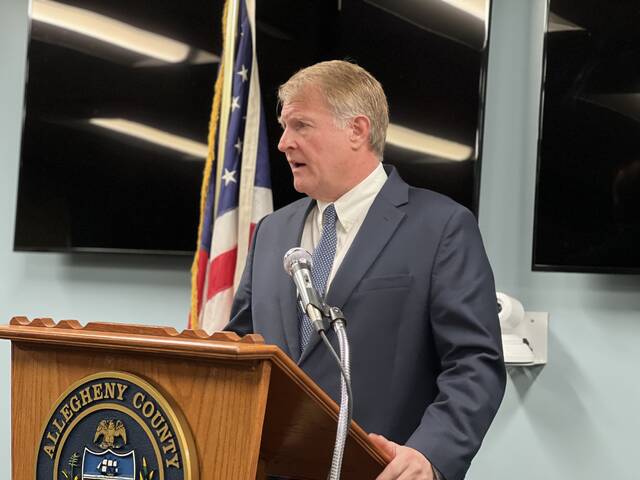

Institute Co-Chair Mark A. Nordenberg said that the goal of the study is to make Allegheny County’s criminal justice system fairer and more cost effective without compromising public safety.

“We have focused on things that we could do ourselves,” he said. “We didn’t want to go to Harrisburg. We didn’t want to go to Washington. We wanted to be able to deal with things that were within our own control.”

In all, the report makes 29 recommendations. They include:

- The city of Pittsburgh and its police department should consider methods of policing that do not rely on stopping people or pulling over motorists for minor infractions.

- The city of Pittsburgh and police should use citations for minor violations instead of arrests.

- The county executive should compare police practices in suburbs with low and high racial disparity.

- The city and county should work to increase transparency of policing practices.

- The court system should race-blind paperwork provided to judges at the preliminary arraignment stage of a case.

- Releasing defendants without requiring them to pay bail should be the default setting during the preliminary arraignment stage.

- The state Supreme Court should conduct an in-depth study on sentencing guidelines and how they contribute to racial disparity.

- The courts should base probation detainer decisions on the severity of new charges filed against the person.

- Officials should prioritize prevention of crime, not punishment.

University of Pittsburgh law Professor David A. Harris, who studies race and criminal justice issues, was on the initial criminal justice task force at the Institute of Politics in 2016 but did not participate in the latest study.

While the broad findings in the report are not surprising, Harris said they are useful.

“When you are resolved to make changes, it tells you with a lot more precision what changes need to be made,” he said. “Systemic problems require systemic solutions, and if you’re not careful and precise, you won’t produce the results you want.”

For 30 years, Harris said, he has been preaching against pretextual traffic stops — for example, pulling over a motorist for a broken tail light.

The study shows it is a huge driver of racial disparity.

Harris said there is still a segment of the population that does not see racism in the criminal justice system.

“That view persists,” he said. “For that reason alone, this kind of very rigorous look at the data is worth doing.”