Months before Corey O’Connor entered the race for Pittsburgh mayor, rumors started circulating that he would try to unseat incumbent Ed Gainey.

The idea wasn’t far-fetched. O’Connor had built a career in public service, first as a Pittsburgh councilman like his father, Bob O’Connor, then as Allegheny County controller.

He had name recognition. He had a legacy. And he had a good story. Bob O’Connor, popular and affable, became mayor in 2006 but died after less than a year in office. Would the son follow in his father’s footsteps?

It turned out the rumor mill was far ahead of O’Connor. He said he didn’t know for certain he would run until just a few weeks before his December announcement.

O’Connor knew being mayor of a fiscally strapped city would bring a demanding workload, one difficult to juggle on top of his duties as a dad of two toddlers.

He talked it over with residents, friends, other elected officials and — most importantly — his wife.

“She was the champion to go for it because you never know when you’re going to get a chance,” O’Connor said.

Katie O’Connor vividly remembers the advice she gave her husband.

“Corey,” she told him, “I think this might be your time.”

Honor thy father

Katie O’Connor said she pushed her husband to run because she feared the city was moving in the wrong direction.

Pittsburgh wasn’t attracting enough development. Downtown was struggling to rebound after the covid-19 pandemic. Core city services — including snow removal, functioning water fountains and maintenance of aging vehicles — were not being delivered efficiently.

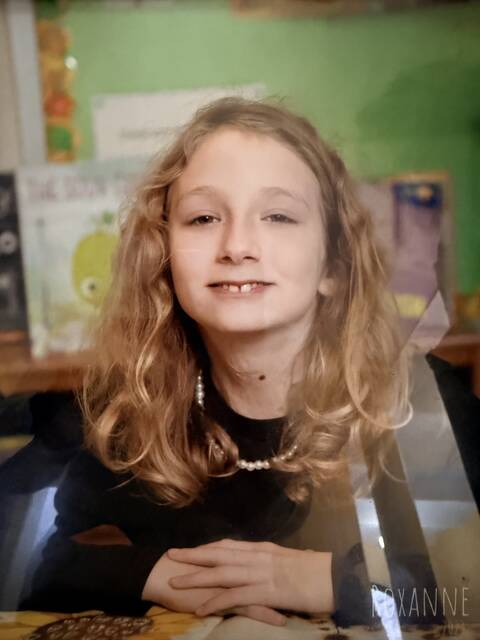

What if their kids — 2-year-old Emmett and 4-year-old Molly — grew up and didn’t think Pittsburgh was an attractive enough city to stay in? What if they didn’t want to raise their own families there?

“I’m worried that we’re not headed on a trajectory that this is going to be a viable place for our kids to come back,” she said. “I think we have to change that.”

That message became a cornerstone of O’Connor’s campaign.

When he announced his mayoral bid, O’Connor pitched a vision of economic growth, fiscal responsibility and improved city services — all areas in which he believes Gainey failed. Throughout his campaign, O’Connor has vowed to make Pittsburgh a city where people want to raise their families.

Related:

• Inside Tony Moreno’s quest to become Pittsburgh’s 1st GOP mayor in nearly a century• O'Connor, Moreno talk city finances, public safety in debate ahead of Pittsburgh mayoral race

hr>

Riding a wave of dissatisfaction among Pittsburghers about the tenure of the city’s first Black mayor, O’Connor defeated Gainey in the May Democratic primary, winning nearly 53% of the vote compared to the incumbent’s 47%.

In a city that hasn’t elected a Republican mayor in nearly a century, many already view O’Connor as the presumptive mayor-elect. Democrats in the city have a 5-1 voter registration advantage, giving O’Connor a significant leg up over GOP candidate Tony Moreno, a retired city police officer who lost a mayoral bid four years ago.

O’Connor, 41, of Point Breeze, served on City Council for a decade before becoming Allegheny County controller in 2022. But he was surrounded by talk of city government long before he stepped into his first elected office.

His father joined City Council in 1991 and stayed until 1998, when he resigned to serve in the administration of then-Pennsylvania Gov. Ed Rendell.

City policy was a common topic of conversation in the O’Connor household. Pride in Pittsburgh was instilled early in young Corey.

O’Connor was 20 and still living with his parents when his father became Pittsburgh’s 58th mayor. After two failed runs, Bob O’Connor finally clinched the office on his third try.

But after fulfilling his lifelong dream, O’Connor fell ill soon after taking office and died of brain cancer on Sept. 1, 2006, having led the city for only eight months.

Now, as the younger O’Connor enters the home stretch of his race for mayor, he reflects on his father’s legacy.

“Hopefully, this is honoring him somewhere,” O’Connor told TribLive.

A mayor for everyone?

Though O’Connor carries a recognizable family name, he had to make his own way, said Doug Shields, a former council member who served as Bob O’Connor’s chief of staff when the elder O’Connor was on council.

“Bob died,” Shields said. “He’s not there to make phone calls for his son. He did that without Bob.”

The Democratic primary in May was tightly contested. O’Connor faced criticism for accepting donations from Republicans and developers, with some questioning whether he’d be able to stand up to President Donald Trump’s administration, whose policies are largely loathed in the Democratic city.

Critics lambasted O’Connor for not denouncing a campaign mailer perceived as racist that was sent by an independent group on his behalf.

Gainey backer Tanisha Long, a community organizer with the Abolitionist Law Center, worries the city could backslide under O’Connor after she felt Gainey made strides to diversify city hall and give marginalized people a voice in local government.

“I really think there are a lot of people Mayor Gainey worked to center — poor people, Black people, people with addiction, the youth, LGBTQ people,” Long said. “And I think we’re going to move away from that Pittsburgh for all to something that feels more corporate.”

Jasiri X, a community activist who founded 1Hood Media, said he’s not convinced O’Connor will give the same attention to people of color and marginalized residents.

“He’s going to replace the first Black mayor in the history of Pittsburgh,” he said. “I would think you want to have conversations with Black leaders and say, ‘Here are my plans, here’s how I would engage the community.’ ”

But 1Hood has not had any such conversations with O’Connor, he said.

Others, however, have backed O’Connor because they believe he will be a mayor for everyone.

Ricky Burgess, a Black former councilman who represented a predominantly minority district, said he supports O’Connor because he believes in his vision to support mixed-income housing and bolster business throughout the city, including in neighborhoods that have historically seen disinvestment.

Burgess pointed out that O’Connor comes from a diverse family, with relatives who are Black, white, Jewish and Christian.

“I think that was something that drew me to him — his understanding of diverse cultures and diverse people,” Burgess said.

Dena Stanley, who heads transgender advocacy group TransYOUniting, said she believes O’Connor will work with the LGBTQ community to ensure its members feel safe in the city.

“I think any person in that seat really has to take in consideration the most vulnerable, marginalized community members — which will be the transgender community and immigrants,” Stanley said. “I feel and I hope that he will make sure we are safe, that he honors that.”

O’Connor in October was recognized by immigrant advocacy group Hello Neighbor as someone who embodies “equity, access and accountability” and ensures immigrants in the city are welcomed, said the group’s founder, Sloane Davidson.

But another immigrant advocacy group, Casa San Jose, expressed concerns about O’Connor taking donations from Republicans.

“If you take MAGA money, you carry MAGA values,” Casa San Jose policy organizer Eddie Carpio said during a news conference hosted by Gainey’s campaign ahead of the primary.

Key legislation

O’Connor is a lifelong Pittsburgher who grew up in his mother’s childhood home in Squirrel Hill. One of three siblings, he attended the former East Hills elementary school and Central Catholic High School before earning a bachelor’s degree in early childhood education from Duquesne University.

He worked in community development for former Democratic U.S. Rep. Mike Doyle before being elected to Pittsburgh City Council in 2011, where he served until becoming Allegheny County controller in 2022.

While on council, O’Connor authored the city’s paid sick days policy, which mandates employees provide paid sick days to workers. That bill, O’Connor said, was inspired by watching his father run a Roy Rogers restaurant and seeing how hard the employees worked. The policy would become his hallmark legislative success.

O’Connor also penned legislation aimed at bringing “commonsense” gun reform to the city, with measures to restrict assault weapons and strengthen background checks. Though the bills were struck down in court, O’Connor believes his fight was just.

He still gets emotional speaking of the impetus for his gun reform bills: October 27, 2018, the day a gunman killed 11 worshippers at Squirrel Hill’s Tree of Life Synagogue.

O’Connor recalled racing to the synagogue.

“The victims were friends. You knew them,” he said. “It was just helpless individuals being murdered by someone with hate in their mind. I think that got me saying, ‘Look, this is enough. We’re done. Let’s fight. It’s time to fight.’ ”

A few years later, on Jan. 28, 2022, the Fern Hollow Bridge collapsed in his district, injuring several people and raising fears about the safety of the city’s spans.

O’Connor quickly got to work drafting legislation to create new oversight for the city’s aging infrastructure. He would push through a bill creating a new infrastructure commission.

South Side Councilman Bob Charland, a staunch O’Connor supporter, said the mayoral candidate earned his respect when he watched him advocate so hard to protect Pittsburghers.

O’Connor can be “like a rabid dog” fighting for gun reform and advocating for city workers when officials contemplated implementing a lesser health insurance plan a few years ago, Charland said.

Charland was a council staffer when the city contemplated changing health care policies for employees. The insurance, he said, wouldn’t be as good.

He recalled watching O’Connor, then a councilman, become animated in a closed-doors council briefing, insisting he wouldn’t allow the city’s workers to be shortchanged.

“Corey was just like, ‘You’re not going to screw over these city employees and that’s just the way it is,’ ” Charland said. “It’s moments like that, I just have the utmost respect for him. He was like, ‘We’re going to take care of our own here.’ ”

Waffle maker

Though O’Connor is eager to make his mark on the mayor’s office, he gets even more animated talking about a job he already has — that of a father.

O’Connor enjoys making waffles for his kids in the morning and letting them lend a hand making scrambled eggs. He tickles his daughter to the tune of Styx’s “Renegade,” the longtime soundtrack to Steelers games, and holds his son in the crook of his arm while they watch Pirates games, his wife said.

Prior to an interview with TribLive this month, O’Connor had spent the night sleeping on his kid’s bedroom floors after they had each awakened in the middle of the night and called for him.

“He loves our kids more than anything,” said Katie O’Connor, who first got to know her husband in high school and married him in 2021. “He comes home sometimes with the weight of Pittsburgh on his shoulders — and the kids don’t feel it. They just feel that dad is home and he’s going to do something silly. He finds a way to park that stuff at the door.”

When O’Connor can squeeze it in, he golfs, a longtime hobby he enjoyed with his father. The two spent many days at the Schenley Park course that now bears Bob O’Connor’s name.

O’Connor went on to coach Central Catholic’s varsity golf team for 17 years. He got the gig at age 20, the youngest varsity golf coach the school ever had.

Neal Shipley, a Mt. Lebanon native who golfs on the PGA tour, praised O’Connor’s coaching. While Shipley, 24, was on the team, they won two state championships and three Western Pennsylvania Interscholastic Athletic League titles.

“He really cared and bought in,” Shipley said.

Winning people over

Sylvia Wilson, a Pittsburgh Public Schools board member who supported Gainey, praised O’Connor.

“I think he’s a dedicated Pittsburgher, just as Ed has been,” Wilson said. “I know he’ll care for what goes on in the city.”

Jon Atkinson, who heads the city’s EMS union, said he initially backed O’Connor largely to oppose Gainey. But after hours of conversations with O’Connor, Atkinson became convinced O’Connor could bring a new vision of fiscal responsibility and a deep understanding of how city government works.

“I’m realistic that it’s not like Corey’s going to assume office in January and by March, everything’s going to be fixed,” said Atkinson, who has raised alarms about overtime spending and aging ambulances. “But I think we’ll have some fresh ideas.”

O’Connor said some of his friends asked him why he’d want to be mayor now. They pointed out he has a good job and the mayor’s office would bring added stress.

But O’Connor said the city he loves needs help. He felt compelled to step up.

“You think you can turn the whole city around,” O’Connor said, “and that’s why you do it.”