Volleys of gunfire. The sounding of taps. The folding of the American flag.

These three moments are part of a final farewell for those who served their country.

They are accolades reserved for veterans — military honors presented at a cemetery or memorial service.

The honors are extended to anyone who dies on active duty, to military retirees and to honorably discharged veterans.

“The gravity of the situations these individuals were in and the actions of those who gave their lives for our country needs to be remembered,” said Dwight Boddorf, chief veteran affairs officer for Allegheny County. “There is nothing more important than giving them a final salute. It’s a tip of the hat to them.”

Boddorf and his office help families and funeral directors with military honors for veterans. Those who died in service are honored every Memorial Day.

“I watched them fold the flag in front of me, so precisely,” said Janet Ladner of West View. Her husband, Raymond Ladner, a Navy veteran of the Vietnam War, died May 7. He was buried May 12 at the National Cemetery of the Alleghenies in Cecil, Washington County. “The shots that were fired and then hearing taps, that was just so beautiful. … The entire ceremony was heartfelt. I will remember that day forever. It gave me peace.”

Ladner said her husband didn’t talk much about Vietnam. When he did, he recalled being on a ship and what he referred to as “his time in the jungle.”

She does remember what he said about the importance of military honors: Because men and women enter the service not knowing what might happen to them, the ceremonies are one final occasion to show appreciation.

For this Memorial Day, as she pays respects to all military veterans who gave their lives, Ladner said she especially will reflect on her husband’s service and the unknown dangers he faced.

“It is different than any other holiday,” said Boddorf. “It’s somber and sacred.”

Military history

Allegheny County has 73,000 veterans, the largest number of any county in Pennsylvania and the fourth highest in the country, Boddorf said.

His office is inside Soldiers & Sailors Memorial Hall & Museum in Oakland, one of the oldest museums in the U.S. dedicated to all branches of service.

Inside is the Hall of Valor that honors veterans, living and deceased. Inductees qualify for the Hall of Valor by being the recipient of medals such as the Medal of Honor, Distinguished Service Cross, Navy Cross, Air Force Cross, Silver Star and Distinguished Flying Cross.

A Pittsburgher, Army veteran Thomas Enright of Bloomfield, was one of the first U.S. casualties in World War I. Buried at St. Mary’s Cemetery in Lawrenceville, Enright has been memorialized in various places, including Enright Court in East Liberty.

Taps and tears

The 24 bugle notes of taps signify a veteran’s final goodbye. When done live, taps is not “played” — it is “sound” or “sounded.” (On occasions when a recorded version is presented, the term “played” applies.)

In 2000, a playing device — or e-bugle — was authorized for use, reflecting the lack of enough qualified buglers in military service, according to Larre Robertson, a national director for Bugles Across America, an organization of individuals who sound taps for all branches of the service. Robertson of Idaho is a Vietnam-era Army veteran who has been sounding taps for 51 years and Idaho state director of Bugles Across America.

The earliest official reference to the mandatory use of taps at military funeral ceremonies is found in the U.S. Army Infantry Drill Regulations for 1891. The Army officially recognized it in 1874, although it had been used unofficially long before that, under its former designation, “Extinguish Lights,” Robertson said.

Today, taps is sounded as the final call at military funerals.

Air Force veteran Tom Beaver, 71, of Bethel Park has sounded taps 1,231 times. A collector of lore surrounding its history, he noted its origins in 1862. Gen. Daniel Butterfield, at Harrison’s Landing Va., reworked the standard bugle call used by the Army during the Civil War. Pvt. Oliver Wilcox Norton, a schoolteacher from Erie County, was the first to sound the bugle call to signal it was the end of the day.

“Each time I sound taps, it is special,” Beaver said. “Even though I have sounded taps all those times, for this family today, this is the first for them.”

A live bugler at funerals is preferred, according to the service organization Military One Source.

“I feel like we are seeing a resurgence of patriotism in America,” said Robertson, the Idaho veteran. “And Memorial Day is a perfect day to recognize those who gave the ultimate sacrifice.”

He said taps is the “toughest 24 notes.” If a bugler misses a note, it’s called “a bugler’s tear.”

“It’s a final chance to tell a family we appreciate what their veteran did for us,” said Robertson, 70. “I have a soft spot in my heart for all veterans. They were all willing to give their life for their country.”

He said there are approximately 4,700 buglers around the world — all volunteers. They cover all 50 states and many countries and attend 3,500-4,000 funerals a year.

“Families often try to pay us, and we tell them, ‘Your family member paid the ultimate sacrifice,’ ” Robertson said.

True heroes and heroines

Lee Ann Jendrejeski recalls hearing taps at the March 30 funeral for her friend Howard Traenkner, 100, a World War II Navy veteran from Harrison.

“Everyone breaks down when they hear taps,” said Jendrejeski of Lower Burrell. “It signified the end of Howard’s life on Earth. He was truly a hero.”

Taps just gets to people, said Julia Parsons, 100, of Forest Hills. She served in the Navy’s WAVES (Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service).

“It’s so poignant and moving. It often brings people to tears,” she said. “It’s good to cry once in a while.”

Parsons said she will be buried at Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia, where her husband, Don, an Army veteran, was laid to rest. She has the flag from his funeral service.

“They fold that flag so perfectly,” Parsons said.

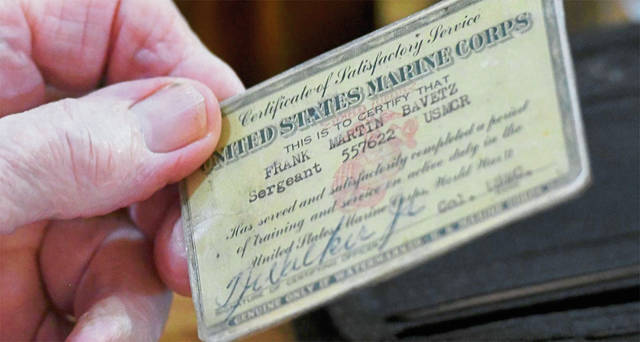

Frank Bavetz, 95, of Harrison earned the rank of sergeant with the 2nd Marine Air Wing. His World War II service included the invasion of Okinawa in Japan.

“The real heroes are the ones we left behind,” said Bavetz, who takes part in rituals at funerals for fallen comrades, placing a pin on the deceased.

Memorial Day has direct meaning for Darla and Norman Madison of Monessen. Their son, Spc. Anthony E. Madison, 27, died in Operation Desert Storm in February 1991. He was one of 13 soldiers from the 14th Quartermaster Detachment, based in Hempfield, who perished when an Iraqi missile struck their unit in Dharan, Saudi Arabia.

“As the years go by, you think of all the life moments Anthony missed,” said Darla Madison, who has a memorial to her son in their home. “We look at that constantly and definitely on Memorial Day. None of us are promised a tomorrow.”

She recalled the military honors for her son.

“When I heard taps, I got chills,” she said. “We have his flag here in a wooden box. I hope people realize on Memorial Day that had it not been for my son and others like him, we would not have the freedom we have today.”

Michael Kraus, curator and historian for Soldiers & Sailors Memorial Hall & Museum, said the military funeral is the ultimate honor for these individuals. Standing near the 14th Quartermaster Detachment display in the museum, Kraus talked about those lost that February day, serving in the water purification unit.

“When these individuals put on a uniform, they don’t know what might happen to them,” Kraus said. “That’s why there are military honors for these individuals when they die, whether it is during wartime or peacetime, when they are serving or whether it’s 10, 20, 50 or more years after they served.”

Flags on Memorial Day

Boddorf’s office distributed 180,000 flags to be placed on veterans’ graves throughout Western Pennsylvania the past few weeks.

“We don’t want people to forget,” Boddorf said.

Jessica King of North Versailles is a Marine who served in the Iraq War. As commander of Veterans of Foreign Wars Pennsylvania District 29, she coordinated with local groups to distribute flags and markers on graves.

The VFW is a nonprofit service organization of eligible veterans and military service members from the active, guard and reserve forces. The American Legion is a patriotic veterans organization.

Members of both participate in funeral services.

“We need to remember them every day, not just on Memorial Day,” King said.

Michael P. Mauer of Squirrel Hill was a sergeant in the Army, serving in Operation Desert Storm as a public affairs specialist and photojournalist. Today, he is public affairs officer for VFW District 29.

He said the most important thing to remember on Memorial Day, as well as every day, is the “ultimate sacrifices these veterans made so we can have freedom.”

Robert Prah of Rostraver is a major in the Army Reserve and commander of the Smithton American Legion. He said he often thinks of how a veteran’s family is going to continue his or her legacy.

“The men and women who fought before us, we can’t forget them,” Prah said. “When I attend one of these funerals, it really makes me think. It makes me appreciate what I have.”

Folding of the flag

Military One Source describes the flag protocol for a veteran’s memorial: A flag is draped on a closed casket before it is folded. When an urn is used, the flag is already in a military fold.

A uniformed representative from the veteran’s service presents the flag to a family member, using language authorized by the Pentagon. Speaking on behalf of the president, the veteran’s military branch and “a grateful nation,” the representative says, “please accept this flag as a symbol of our appreciation for your loved one’s honorable and faithful service.”

Amy Lytle of Murrysville is the niece of Howard Traenkner, the Navy veteran from Harrison who died this year at 100. She has his flag, which her mother, Traenkner’s sister, handed over to her.

“I cherish my uncle’s flag,” said Lytle, who was Traenkner’s caregiver in his later years. “My uncle was proud of his service. When you go in, you don’t know what might happen to you. He did it because he loved his country.”

3-round volley

At military funerals, an honor guard fires three volleys from rifles. The trio represents duty, honor and country.

As detailed by Veterans United, the tradition comes from battle ceasefires, where each side would clear the dead. The firing of three volleys indicated the dead were taken care of. The firing party in a ceremony is three, five or seven, plus a firing party commander. Each fires three times.

At a funeral, shell casings are presented to the family. Sometimes they are placed inside the flag. Other times they are put in a container.

After the May 12 service for her husband, Janet Ladner walked alone as she carried the flag back to her car.

“Attending my husband’s funeral was the toughest thing I ever had to do,” she said. “It becomes real that he’s gone. The service gave me closure. It makes it complete. The entire service was beautiful. It was really a nice honor for Ray.”