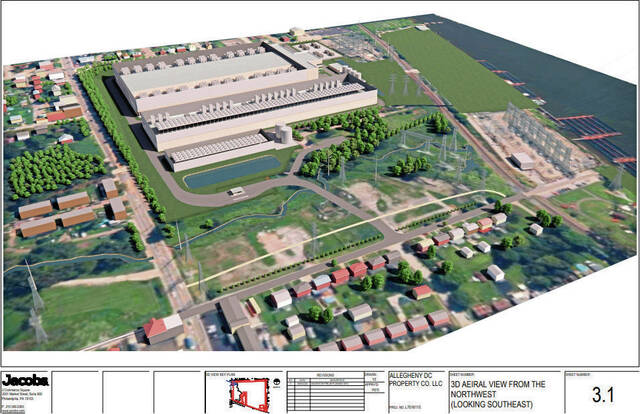

Since developers revealed the initial details of a proposed data center at the former site of the Cheswick Generating Station in Springdale in August, the community has come armed with questions about the project.

In December, Springdale Council voted to approve a conditional-use application from developers seeking to build the center, but there’s still plenty more to come before construction crews arrive at the site.

Here’s everything we know so far:

The basics

Data centers are used to store digital information and house the enormous computing power necessary for the development of technology such as artificial intelligence.

Though still a relatively new land use, thousands of centers are already spread across the United States, especially concentrated in Northern Virginia. Other data center projects are currently underway in Upper Burrell and Homer City.

The one proposed in Springdale would be massive.

The site, which measures about 47 acres, would house a 565,000-square-foot hyperscale data center and a 200,000-square-foot mechanical cooling plant.

Taken together, the two structures would have a total area around the size of PPG Paints Arena.

A zoning request granted by the borough would allow the center to stand 60 feet tall, or 75 feet with rooftop equipment.

Brian Regli, a consultant for land developer Allegheny DC Property Co. who has served as the main spokesman for the project, estimated the buildings would have a lifespan of 40 to 50 years.

Regli has said the center would be built with AI development in mind. Though his company doesn’t have any tenants lined up, he said they’d be looking to woo large tech companies.

The Porter Street site was formerly owned by Charah, the company responsible for demolishing the former power plant. But Allegheny DC purchased the property in late November for $14.3 million

Allegheny DC is a holding company owned by Davidson Kempner, a large New York-based hedge fund, which is bankrolling the project. The firm previously invested billions of dollars in a Portuguese data center complex that went online earlier this year south of Lisbon.

Engineers and architects from Jacobs Solutions designed the preliminary sketches of the Springdale center, and attorneys from Pittsburgh-based Babst Calland represent the developers.

Regli said his company also is working with Vipa Digital, a London-based data center consulting firm that has developed complexes around the globe.

Attorney Tom Kloehn, hired by Springdale resident Mitch Karaica, previously served as opposing counsel during proceedings.

But Kloehn, a staff attorney at West Virginia-based Appalachian Mountain Advocates, confirmed Karaica had withdrawn as an objector the project in November. He didn’t provide a reason for the reversal.

Energy use

Though it’s perhaps the most concerning topic for residents, the site’s potential effects on the energy grid and prices are still hazy.

Data centers require immense amounts of energy at all times to power their computers, which can strain local electrical infrastructure and raise costs for consumers.

Regli has said the site would seek to draw a maximum of 180 megawatts of energy at any one time.

An average American home draws about 1,200 watts of power, meaning the energy used by the proposed data center could power about 150,000 homes.

The site sits near the border of utility areas covered by Duquesne Light and FirstEnergy, parent company to West Penn Power. Each company maintains a substation near the former power plant.

Allegheny DC has paid for power studies from both firms to determine how it will meet its demand, Regli said.

More than likely, the project will require new infrastructure to power it, but Regli said his company will fully cover the cost of any additions.

In case of an outage or emergency, the center would also maintain upward of 100 backup generators that could make the site temporarily self-sustaining. Regli said the generators would be diesel-powered, but Allegheny DC is considering natural gas as an alternative power source.

Developers are also considering potential on-site self-generation options for times of peak energy demand. Regli said this could look like battery storage, natural gas, geothermal power or solar panels, which would be used to ease consumption.

But the center would still draw the vast majority of its energy from the grid, he said.

The potential for price hikes for consumers’ power bills remains a concern for many residents, but it’s unclear what effect the center would have on pricing.

Water

In addition to its vast electricity needs, the center would require large amounts of water to hydraulically cool its computers.

The source of that water: Springdale’s municipal supply.

Developers have said that cooling would be done using a closed-loop system, which would continually recycle water.

That means the system would require a large amount of water to initially “charge” the coolers, but it would only take on further water in small increments to compensate for evaporation.

That charging period would likely require around 500,000 gallons of water, or about 3/4 of an Olympic-sized swimming pool.

Regli said the “charging period” can be spread over the course of days or weeks.

Noise

The constant noise that will likely emit from the center has been a significant source of concern for residents in Springdale and just across the municipal border in Cheswick.

On average, Regli said, the developer’s goal is to keep the decibel level in the 40s, meaning it would emit something close to a quiet refrigerator hum.

In a projection of the maximum decibel levels expected from site equipment, Pittsburgh-based sound expert Jeff Babich said the noise along the property line at Pittsburgh Street would be about 57 decibels.

The noise, mostly produced by cooling fans, would be a “whooshing” sound similar to white noise.

When backup generators are used or tested, however, the noise level likely would be much louder — more like the sound of a loud lawn mower, Regli said.

In a condition for the project’s approval which the company has agreed to, noise levels could not exceed 85 decibels at the property line — about the level of city traffic — unless a power outage occurs.

Regli said the developers were also considering aesthetic shields on the facility to further muffle sound as well as landscaping, like earthen mounds, near Duquesne Avenue to protect Cheswick residents.

The generators would each require monthly testing for 15-30 minutes, however. With more than 100 generators to assess, that could lead to hours of noise each month.

In a condition of the site’s initial approval, the borough said backup generator testing could only be done between 8 a.m and 6 p.m. on weekdays.

Developers could plan that testing with the borough, which Regli said could take place for longer durations over a few days or for shorter periods over longer stretches.

Jobs

Regli has continually said 80 to 100 jobs would be created at the site.

Those jobs would include security guards and custodial staff as well as more technical positions servicing the data center’s servers. At any one time, he said, 40 to 60 people would be on site.

Many of the jobs would require some mechanical know-how, but that doesn’t mean applicants would need to have advanced degrees, he said.

That’s in addition to the likely hundreds or thousands of temporary jobs that will be required to construct the facility.

Taxes

Anthony Barna, a Pittsburgh-based real estate appraiser, offered his assessment of the real estate tax revenue the project may ultimately generate during testimony before council

A paid expert of the developer, he based his estimate on the anticipated cost to build the data center, which he projected to be between $420 million and $770 million.

Using those figures, Barna said he conservatively estimates the site would generate about $658,000 in real estate tax revenue for the borough each year. That’s in addition to $1.46 million for Allegheny Valley School District and $434,000 for Allegheny County.

Currently, the site’s owners pay $17,000 to the borough, $38,000 to the district and $11,000 to the county in yearly real estate taxes.

When Allegheny DC acquired the property from Charah, both companies were also required to pay a real estate transfer tax equivalent to 1% of the sale.

Half of that revenue goes to the state, and the other half would be split between Springdale and Allegheny Valley School District.

Springdale and the school district also would collect taxes from the employees at the site.

Lighting

In response to a community suggestion, developers have agreed to abide by the standards of the City of Pittsburgh’s “Dark Sky Ordinance.”

That means all the LED lights at the site would be downward facing or otherwise shielded or dimmed unless required for security reasons.

In another condition for approval negotiated between the borough and the company, any lighting used to illuminate parking areas or driveways would be directed away from residential properties.

Security and Public Safety

The site would be manned at all times by security. Regli said the guards are typically unarmed.

A security vestibule would sit near the entrance road to the site, which would be near the intersection of Duquesne Avenue and Oak Street in Cheswick.

The entire perimeter of the 47-acre area would be fenced in with an anti-climb barrier. Springdale Planning Commission approved Allegheny DC’s request to make that fence 8 feet high.

Among the several conditions imposed on the project, one says the agreement may require developers to cover the cost of “equipment and apparatus reasonably necessary for police, fire and emergency services” to provide their services.

Another condition says developers would have to periodically coordinate with Springdale’s emergency management coordinator to assess responses to the center and audit equipment. If developers and the coordinator agree that new equipment is necessary for emergency response at the center, Allegheny DC will have to bear the cost, the condition says.

Traffic

Models show vehicles would enter the site via an access road at the intersection of Duquesne Avenue and Oak Street.

But the borough has asked developers in another condition to evaluate whether the main entrance can be placed on Pittsburgh Street instead.

Engineer Mark Laborte said projected traffic at the site showed about 65 vehicles entering in the morning and 58 in the evening.

Regli said residents could expect increased traffic during construction, but truck deliveries would be relatively infrequent after completion, according to developers.

Environmental concerns

Many environmental concerns hinge on the method by which the center would be powered, which remains unclear.

The backup generators, which will use diesel fuel or natural gas, would produce at least some emissions from burning hydrocarbons.

Local environmental groups have become involved in organizing against the project. The groups include Westmoreland County-based Protect PT, Pittsburgh-based Breathe Project and Environmental Health Project and a local chapter of Moms Clean Air Force.

Environmental Health Project has previously offered a dispersion map of potential pollutants from the site. Based on wind and weather data, the map showed pollutants could reach as far as Brackenridge, Lower Burrell and Penn Hills.

The group has not yet modeled the amount of emissions the site could produce, however, according to one of its representatives.

Several residents and council members have inquired about carbon capture technology for the generators, but it’s indefinite if developers will move in that direction.

The data center in Upper Burrell plans to produce much of its own electricity through on-site natural gas wells, but that’s likely impossible at the Springdale site, which has a much smaller footprint.

Green space?

St. Mark’s Cemetery and the Harwick Miners Memorial, the final resting place for dozens and a monument to the 179 miners who died in the 1904 Harwick mine disaster, sit in the middle of the former industrial site.

Regli said the company would improve the burial ground, making it a sort of “grotto” for visiting residents. A path leading to the memorial would branch off the entrance road.

The consultant also said he hopes to build a hiking trail along Tawney Run connecting the nearby Rachel Carson Trail to Cheswick’s Rachel Carson Riverfront Park.

A riverside park at the site, however, is unlikely, Regli said.

The project’s path forward

Months of meetings and discussion led to three Springdale bodies ruling in favor of the center.

Springdale’s planning commission recommended the project for approval, the borough’s zoning hearing board approved several variances requested by developers and borough council finally approved Allegheny DC’s application with conditions in December.

The project is now in its land development phase.

In the coming months, developers will have to return to Springdale with more detailed models in hand to present a preliminary — and then a final — land development plan, according to borough Manager Terry Carcella.

Like the conditional-use process, both of those plans will have to appear before Springdale’s planning commission and borough council.

This time, however, the final decision sits with Allegheny County officials.

Unlike most local municipalities, Springdale doesn’t have its own Subdivision and Land Development Ordinance (SALDO) to govern the way plots are divided and how they can be developed. The borough defers to the county’s SALDO.

Borough council will be able to offer recommendations to the Allegheny County Economic Development Planning Division, but it’s that body that ultimately will approve or deny the developer’s plans.

With approval of a final land development plan, Allegheny DC could finally come back to the borough for a zoning and building permit, Carcella said, which would be granted by a Springdale zoning officer.

It’s only with those permits in hand that the company could begin construction at the site, Carcella said.

Allegheny County Health Department spokesman Ronnie Das said his department anticipates receiving an air quality permit for the project but hasn’t received one yet. Das said there also could be plumbing plans that ACHD would inspect.

Brian Regli, a consultant for Allegheny DC who has served as the main spokesman for the project, told TribLive he hopes to be back in Springdale in early spring with a more detailed design.