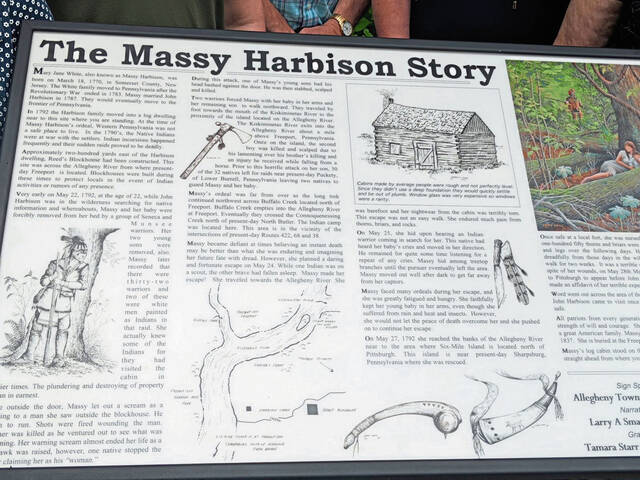

The Allegheny Township Historical Society dedicated a historical marker and placard honoring pioneer woman Massy Harbison on Sunday.

Massy (also spelled Massey in some documents) Harbison was captured by Native Americans in her cabin along the Allegheny River, in what is now River Forest Country Club in Allegheny Township. According to Phyllis Framel, a founder of the Allegheny Township Historical Society, the precise location is along the Tredway Trail, at the women’s tee of the golf course’s fourth hole.

Among the most admired pioneer women in the state and perhaps the era, Harbison famously outwitted her Native American captors after they captured her and killed two of her children, on May 22, 1792.

The new historical marker was dedicated on the 230th anniversary of Harbison’s capture.

“It was a project that was a long time in the making,” said historical society vice president Kathy Starr. “It means that in Allegheny Township, we value history. We used the best possible construction we could so it will last for a hundred years.”

David Harbison, a direct descendant of Massy Harbison, was on hand for the unveiling of the marker. He said he was pleased that the community is preserving her story in this way.

“It’s a good recognition. There were a lot of women that were captured, and she’s no different than a lot of settlers of this area,” Harbison said. “The only thing that makes her unique is that her story has been recorded. I think she’s representative of a lot of families. The descendants are here and still going strong after 230 years.

“It was a clash of cultures. They refer to these (Native Americans) as savages, but they were people who were protecting their own land.”

With unfathomable fortitude, Harbison — then 22 and pregnant with her fourth child — engineered her escape after being threatened with a tomahawk. She watched the Native Americans kill one of her sons, and then glimpsed the fresh scalp of another son they had killed.

She forged her way through the wilderness, with no shoes, from Butler to Fox Chapel, carrying her remaining son as she was tracked by her captors.

The brutality is shocking, but such savagery ran rampant in Pennsylvania and the Allegheny River valley at that time. Both white men and Native Americans were guilty of atrocities. The government of Pennsylvania offered bounties for Native American scalps, according to historical accounts.

History in the making

Harbison’s capture was among numerous Native American attacks on settlers along the Allegheny during what was dubbed the Indian wars and uprisings. Harbison, her husband and their three children lived on the frontier in present-day Allegheny Township, with the land just across the Allegheny River considered Indian Lands.

Massy Harbison’s 70-mile, six-day odyssey started at River Forest, then traveled to an Indian camp in Butler and ended with her rescue along the Allegheny River in the area of today’s Fox Chapel Yacht Club, according to two former Alle-Kiski schoolteachers who studied Harbison’s life. Their booklet, titled “Escape,” retraces the pioneer woman’s route, syncing historical and current maps with Harbison’s own published account.

“Lazily I am thinking it is strangely quiet, there are no birds calling as I pull up my coverlet and fall asleep,” Harbison wrote. “Only to be roughly pulled from my bed by my feet, by Indian warriors! Look out, I’m instantly alert …”

The booklet was assembled by the late Drenda Gostkowski of Winfield and Susan Przybylek of Buffalo Township. They published only 200 copies of “Escape,” which was used as a fundraiser years ago; it is no longer available. In addition to “Escape,” Gostkowski edited a version of Harbison’s account of her capture, which is available at the Heinz History Center and other places.

Harbison’s ordeal also was the subject of a local theater production. Written by Ren Steele, an Allegheny Township supervisor and co-director of the Freeport Theatre Festival, the historical drama “Massey Harbison” was first produced in 1998 for the Freeport Theatre Festival. It became one of the theater’s most popular productions.

The location of Harbison’s cabin has been determined by numerous sources, though without a formal archaeological survey of the site nor likely the nearby fort, according to state records and the Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

Framel said the late Wynn Tredway — who developed and owned the River Forest golf club — had an idea of the exact cabin location.

“Massey Harbison provides one of the earliest eyewitness accounts of what life was like on the edge of Western civilization in our region at that time,” Framel said.

When Tredway first bought the site in 1965, there might have been a timber or two remaining from the foundation of the cabin. The only clue left is a plaque installed on the golf course by the Daughters of the American Revolution.

“Mr. Tredway tried the best he could to preserve what artifacts he could during the construction of the golf course,” Framel said.

Of ‘Indian Lands’

The Harbison cabin in Allegheny Township was located intentionally near “Indian Lands.”

These pioneers were waiting for the Indian wars to end, opening up the “Indian Lands” across the Allegheny River, according to the booklet “Escape.” Delaware and other tribesmen raided and abducted Harbison and her three children at the cabin while her husband, John, was away scouting for Native Americans for the U.S. government.

After Harbison was abducted, one of the tribesmen, whom she described as Delaware and others, claimed her as his squaw. As her oldest son Samuel fussed, her captors killed the boy at the cabin. Then shortly into her journey with the Native Americans, they killed her second son, Robert, after he fell from a horse that rolled down a steep embankment to Kiski Junction, the Allegheny’s confluence of the Kiski River.

“Robert cries for Samuel, he is hurting, he is only five,” Harbison wrote. “No! I swoon and fall once more, John is in my arms for Robert is killed, his scalp displayed bright red before my eyes. Once again, I am beaten into action. The cold water brings me to my senses! This is no dream but a living nightmare!”

Once in the “Indian Lands” across the river, near Freeport, her captors made Harbison wade across “Big Buffalo Creek” that was “deep, cold and swollen with spring rains.”

Harbison and the Native Americans crossed the Connoquenessing Creek to reach a Native American camp known as Salt Lick, in the vicinity of Route 68 east and Route 38 north in Butler.

She escaped when one of the captors left and the second fell asleep. Harbison meandered in many areas, including today’s North Park and Fox Chapel. She wrote about eluding the Native Americans when she found fresh moccasin tracks and a hunting camp with a still-hot fireplace.

Just hearing gunshots sent Harbison into a panic during her escape.

“I must hide. A tree, another downed log. I rise up from the ground to move behind it. Hide! Wait! Snakes! Rattles! Yet more snakes, a ghastly writhing ball! I leap backward, quickly push off the ground and veer left. My heart pounds, I must not cry out!”

Harbison recognized Squaw Run, a creek in the Fox Chapel area, and followed it to the Allegheny River.

But she was weary and collapsed in an abandoned cabin: “Despair heaped upon an already despairing spirit,” she wrote. “For here would I lie down and die seeking the only rest I know from so much misery. As I sink to the earthen floor, John in my lap, I am overcome with his need for me. For if I should give up what of my babe? As I look into his trusting child’s eyes and feel his still warm body reach out to me, I determine to live. I hear water splashing against a bank. What water?”

Harbison found the Allegheny River and was rescued. About 150 thorns were pulled from her body, including some that went through her feet, according to her account. She was taken to Pittsburgh and gave her account to a magistrate.

After her rescue, Harbison’s husband built a home and grain mill, whose foundations are on private property, but still visible along the Butler-Freeport Trail and Buffalo Creek in the winter. The Boy Scouts erected a kiosk with a historical marker near the spot.