Donald Trump campaigned, in part, on the promise to bring down grocery prices, but seven months into his second term, the result is a mixed bag.

Coffee and beef prices are up. Baby formula, eggs and Cheerios are down. Toilet paper and diapers have held steady.

“The obvious one is coffee,” said J. Brian O’Roark, an economics professor and the B.K. Simon Fellow at Robert Morris University in Moon. “My wife and I were just down in (Pittsburgh’s) Strip District, and I was talking to a coffee retailer. They said they’ve already seen their prices go up, and they’ve passed that cost on to consumers.”

Prices have gone up 2.67% since June 2024 across the wide variety of categories measured under the Consumer Price Index, data compiled by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. That time frame includes the last six months of Joe Biden’s presidency.

Prices strictly under the “food at home” category in the Consumer Price Index have gone up 2.48% in that same span.

Shoppers say they are feeling the pinch.

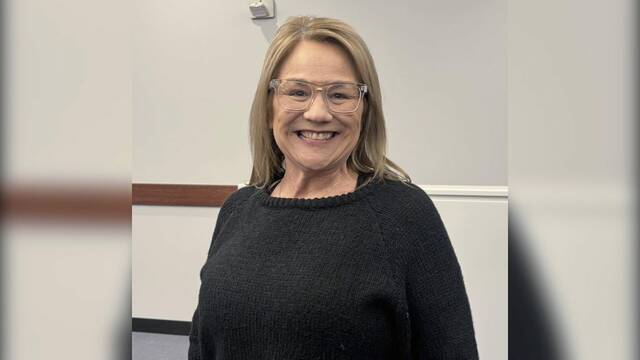

“Meat prices have really skyrocketed,” said Cathy Hanks of Delmont, who was loading groceries into her vehicle Wednesday outside of her local Walmart. “Eggs have come back down, but it’s gone up across the board. I’m retired, so living on Social Security, shopping for groceries is tougher on my budget now.”

The largest jump in the foods category is meats, poultry, fish and eggs, which have seen a 5.62% bump in prices over the past year, according to Consumer Price Index data. Egg prices were affected by widespread bird flu that has since lessened in impact.

TribLive tracked prices from April 9 to July 22 at retail giant Walmart and found many prices have changed little, if at all.

Some of the items that have experienced a price change are Enfamil baby formula, which has decreased from $20.97 in April to $18.83 in late July. Meanwhile, a 32 oz. canister of Maxwell House coffee has increased from $14.64 in April to $17.16 in late July.

Shopper Jessica Duffey, 36, of Buffalo Township used to go to her local Aldi for more affordable grocery options but said that store’s prices are now on par with her local Walmart.

“I think everything has increased drastically, to be honest,” she said.

Crystal Mount of Murrysville said her grocery bill continues to climb.

“We’re a family of five — seven if I have my step-grandkids over — and so you don’t always think about it, but a half-dozen or more chicken breasts for dinner, it all adds up over time,” Mount said. “Eventually, you look at your budget and think, ‘Wow, I’m spending so much on groceries.’”

Anne DiFatta, 27, of Freeport was picking up groceries at the Walmart in Harrison on Wednesday morning. DiFatta said most of the basic items on her shopping list — dairy, eggs and especially meat — have increased in price. She said she and her fiancee try to go to local farms for produce and buy their eggs from families who raise chickens. But for items like cat litter, she can’t avoid the grocery store.

“We have to budget more,” she said. “It’s a little bit tighter of a budget now than it was before.”

Shopper David Uruk, 72, of Harrison said he expects tariffs to cause price hikes across the board.

“Well, President Trump says that prices are down,” Uruk said. “But ask anybody about the price of ground beef. I’m retired, and I’m fine, but I don’t know how a young family can afford to feed a family anymore.”

Joe Meger, 70, of Tarentum said he believes the economy as a whole is on the upswing. He said he had to dip into his savings under the Biden administration.

“I’m happy with the way things are going,” he said.

A matter of time

The fear that tariffs levied by the Trump administration on other countries’ imports would dramatically hike the cost of everyday products hasn’t been realized, but some economics observers say that might be only a matter of time.

The effects of tariffs take time to make their way through the world economy, O’Roark said.

“The first Trump administration kind of proves this out,” he said. “In his first term, he put tariffs in place, and things didn’t become more expensive overnight. There are contracts that have to be completed at whatever the bargained prices were.”

Protectionist tariffs enacted against China, the European Union, Canada and Mexico during Trump’s first term reduced real income in the U.S. by about $1.4 billion and adversely affected the nation’s gross domestic product, according to an analysis published in the Journal of Economic Perspectives in 2019. Those first-term tariffs were primarily aimed at steel imports. Many of them were lifted less than a year after being imposed, and they pale in comparison to the scope and scale of what has been suggested and, in some cases, imposed during Trump’s second term.

Some grocery prices aren’t affected by tariffs.

U.S. beef prices, for instance, have been steadily rising over the past 20 years because the supply of cattle remains tight while beef remains popular.

For shoppers, the average price of a pound of ground beef rose to $6.12 in June, up nearly 12% from a year ago, according to U.S. government data. The average price of all uncooked beef steaks rose 8% to $11.49 per pound. But the administration’s threat to impose a 50% tariff on Brazilian products will undoubtedly affect beef. The only country that imports more Brazilian beef than the U.S. is China.

Other food prices are undoubtedly affected by tariffs.

Coffee, for example, is not grown in the United States. No matter where a company sources its coffee, O’Roark said, the worldwide price point generally follows that of the Brazilian coffee industry.

“If there’s a 50% tariff on Brazilian products (starting in August), that’s going to affect the prices of coffee, generally speaking,” he said.

Food industry analyst and “Supermarket Guru” editor Phil Lempert said the U.S. has not yet felt the full impact of recently imposed tariffs.

“I don’t think we’ve seen anything yet, even though grocery prices have gone up 26% since the pandemic,” Lempert said. “We continue to see labor costs going up, we have climate change affecting the availability of our crops, we see exporters in other countries questioning whether to play this tariff game — we’ve certainly seen that with Canada.”

Lempert said the next six to nine months could see food prices climb even higher.

“We’re seeing a pullback on spending in certain categories like snacks and more indulgent foods, whose sales are down,” he said. “We’ve had this century with America having the cheapest food supply in the world — not anymore.”

Tariffs: Intention vs. effect

Unlike a lot of other retail products, groceries are uniquely susceptible to the effects of tariffs and inflation, according to Ryan Young, senior economist with the Competitive Enterprise Institute, a libertarian think tank based in Washington, D.C.

“The profit margin for grocers is 1% to 2%,” Young said. “That makes groceries very responsive to inflation or tariffs. When a company pays a tariff on one component of a machine they make, that can take a year to make its way through the supply chain.”

Part of Trump’s logic in imposing tariffs is that it will stimulate American companies to make their products here. But with some categories of groceries, that’s just not possible, Young said.

“With produce like coffee and bananas, almost none of them are made in the U.S.,” he said. “We get bananas from Nicaragua, Guatemala. We get coffee from South America and Africa. There’s one experimental tea plantation on an island off the coast of South Carolina. Pretty much all of our tea comes from India, China and a few other places. We don’t grow those products in America, and yet they’re tariffed. So for those, the argument that we’re getting economic benefits from tariffs doesn’t hold up.”

Lempert agreed.

“We can’t grow coffee here. We can’t grow a lot of berries, and so much of the produce that used to be grown in California has moved to Mexico and central America because of fires, droughts and other climate-related issues,” he said. “It’s just foolhardy to say that we’re going to bring all of that agriculture back to the U.S.”

The U.S. Federal Reserve announced Wednesday it would hold interest rates steady. That was predicted, but O’Roark said it could impact the U.S. food economy through the nation’s farmers.

“They’re dependent on loans year-to-year, so if those short-term rates hold steady, that can be good in a way, because farmers can plan ahead,” he said. “But so many farms, even big farms, rely heavily on lending. And if the Fed is going to keep those rates high because they’re worried about inflation, historical data shows us that farmers will pass that extra cost on to consumers.”

And while tariffs on countries such as Mexico — which are set to increase Aug. 1, barring a new trade deal — have not shown up in a noticeable way on shoppers’ grocery bills, that could change come winter.

“I was talking with a colleague about just how much produce we get from Mexico, particularly in the non-growing season we have in the U.S.,” O’Roark said. “If the tariffs that have been suggested go into effect, or even if they’re not quite as high as expected, fresh fruits and vegetables are going to be much more expensive.”

That impact may be lessened for a massive retailer such as Walmart, but O’Roark said the company won’t be able to escape it.

“They have a lot of pricing power, and they can absorb some of those higher costs for a period of time,” he said. “But Walmart stock has not been a rocket ship lately, and shareholders of a publicly traded company will begin to ask questions about keeping costs under control.”

In an earnings call with investors on Tuesday, international retailer Procter & Gamble announced its profits will take a roughly $1 billion hit owing to Trump’s tariffs, and, as a result, it will increase prices on about 25% of its products. Other companies including Nike, Walmart and car manufacturers Ford and Subaru have also announced similar intentions to raise prices to absorb the cost of new tariffs. According to Kelly Blue Book, the price for a base-model Ford Escape largely stayed steady around $29,900 from April to June, before dropping slightly to $28,436 this month and climbing up to just over $31,000 as of July 22.

Some companies opted to stockpile items in advance of tariff hikes, but that also is just a temporary measure.

“We get avocados from Mexico, we get grapes from Chile,” O’Roark said. “As those inventories get sold, and those contracts expire, new contracts will be set for a lot of things you see in the grocery store, and unless something very strange happens, we should see those prices start to climb.”