https://triblive.com/local/valley-news-dispatch/remember-when-horrific-steel-mill-accidents-spur-special-memorials-reports-of-hauntings/

Remember When: Horrific steel mill accidents spur special memorials, reports of hauntings

In the early hours of June 23, 1910, John Mitchell died in an unimaginable way at the West Penn Steel plant in Brackenridge.

Working as a tongsman at the mill, his job was to oversee the handling of the hot steel ingots coming from the furnace.

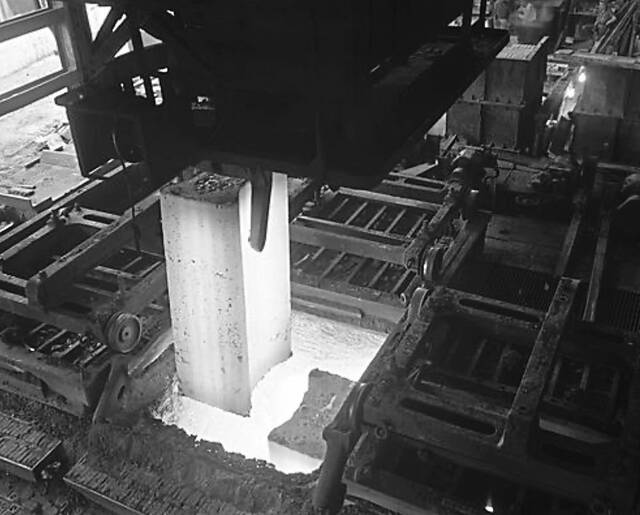

For the steel to be worked successfully, it must reach a proper, uniform temperature throughout its mass. To accomplish that, the newly cast ingot is taken to a soaking pit, which is a furnace that reheats the steel to a temperature of 2,200 to 2,300 degrees.

The pit in the floor of a mill is covered with a sliding roof panel. While in the pit, the steel in the ingot has time to a reach uniform temperature and can be further heated, if necessary, for maximum workability.

Mitchell had just given the order that the doors of a nearby pit should be opened. A boy, Robert Trees, who was in charge of the doors over the soaking pits, pulled the wrong lever. Mitchell was dropped 18 feet to the bottom of a pit over which he was standing. It contained a white-hot ingot of steel.

Fellow workmen who rushed to the scene reported that Mitchell’s body was entirely consumed by the hot ingot. They said only a faint outline of his body was visible.

Trees, whose age at the time is unknown, was so distraught by the result of his mistake that he was placed under the care of a physician for several hours. In those days, boys as young as 13 worked in the mills.

In 1916, Congress passed the Keating-Owens Act that prohibited children younger than 14 from working in industrial settings.

Mitchell, 35, was a resident of Edgecliff, a community located directly across the Allegheny River from the mill, near the mouth of Chartiers Run. He was married and the father of five young children.

In this type of mill accident, there is no body to return to the family for burial.

These accidents also are extremely traumatic for co-workers. Some mills have developed practices or rituals in the event of such occurrences.

In the 1970s, a resident of Lower Burrell was working with the bridge unit of the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation in Green Tree.

At that time, workers were replacing the existing Brady Street Bridge, which connected the Oakland area with the South Side. To construct the new bridge, now known as the Birmingham Bridge, it was necessary to acquire additional property for the bridge and its ramps.

The state sent right-of-way personnel to meet with the land holders to discuss the proposed work and negotiate a selling price for the properties. Accompanying the right of way personnel were several members of the bridge unit, including two engineers, a senior engineer and a trainee.

In one of the homes, the older engineer noticed a block of steel the size of a half-stick of butter on a living room mantel. It was engraved with a name and date. He was about to ask about the object but was signaled by his younger assistant not to do so.

After leaving the home, the younger engineer — who had family members in the steel industry — told him the block of steel was given as a memorial for a loved one whose body had been consumed in a mill accident.

A Facebook site devoted to the steel industry, Steel Mill Pictorial, has many stories about mill accidents, including ones where a worker’s body was entirely consumed.

In some mills, a block of steel equal in weight to the missing worker would be given to the family to be buried in a closed coffin. Occasionally, the worker’s body was consumed by contact with slag. In those cases, an equal weight of slag was given to the family for burial.

The rituals and practices varied from mill to mill. In some, a piece of steel from the pour was buried at the mill as a memorial. Some mills buried them under the floor and some buried them on the grounds outside the mill buildings. There also are stories that the ingots involved sometimes would be set outside as tainted.

In Allegheny County between July 1906 and June 1907, there were 195 casualties in the steel mills. Of these, 24 workers died from falls from a height or into a pit. In this same 12-month period, there were 509 accidents that involved hospitalizations and 76 that resulted in serious permanent injuries.

Because of the many deaths in the area’s mills, there arose stories of hauntings. Today, some mills and former mill sites offer ghost tours during the month of October.

One of the most famous stories in the Pittsburgh area occurred at the Jones and Laughlin Steel Corp.’s No. 2 shop at its South Side mill.

The spirit of a steel worker, James Grabowski, reportedly haunted the mill from the time of his death in 1922 until the mill was razed in 1960. He died from falling into a ladle of molten steel. Over the years, many workers claimed to see his apparition and hear his cries for help followed by laughter.

In the Alle-Kiski Valley, Gerie Rossi of Lower Burrell relates a story told by her father, John Schenk, who worked at Braeburn Alloy Steel. As the story goes, Schenk was sitting in the break room adjacent to the rolling mill, when a supervisor and friend named Jack Wilks walked past him.

Schenk said, “Hello.” Wilks did not respond, prompting Schenk to ask, “Can you not say hello?”

He watched as Wilks walked across the room and passed through a solid wall. It was then that Schenk realized he had seen a ghost, as Wilks had passed away some years before.

Copyright ©2026— Trib Total Media, LLC (TribLIVE.com)