Prior to March of 1936, there had been 63 inches of winter snowfall in the upper Allegheny River Valley.

Warm weather, coupled with melting snow and two days of torrential rains, resulted in one of the region’s worst natural disasters — the great flood of 1936, commonly known as the St. Patrick’s Day Flood.

It is a common misconception that the locks and dams were constructed on the Allegheny River in response to this flood. The dams in the area were constructed in the late 1920s for the purpose of making the river navigable.

Before the construction of the dams, there were periods when river traffic came to a halt because of lack of rainfall and low water levels.

One of the areas hit hardest during the St. Patrick’s Day Flood was the village of Braeburn. Part of the reason for the devastation was the presence of Lock and Dam No.4 between Natrona and Braeburn. The Natrona side of the river was protected by the massive concrete structure of the lock but on the Braeburn side of the river, there was only a small wingwall at the end of the dam to protect the embankment.

Once the fat-moving floodwater breached the area around the wingwall, it cut a channel around the dam. Within a week, this channel expanded to an area 300 feet wide and 2,000 feet long.

The floodwaters reached 12 feet high on the side of the Braeburn train station and swept away the railroad turntable adjacent to it. The losses included nine houses, the post office and the office of the Braeburn Steel Company.

Numerous houses in Braeburn were inundated with water and damaged beyond repair. The Braeburn Hotel survived but had more than 2 feet of mud on its elevated first floor.

The following is a chronology of events that took place in March of 1936 at Braeburn in attempts to stem the flood:

March 20

The Army Corps of Engineers considered using dynamite on the dam to save the railroad bed and main line of the Pennsylvania Railroad. Seven deputy sheriffs were dispatch from Greensburg to Braeburn to prevent looting.

March 21

The Army Corps of Engineers sent the steamer Pennova, the first boat to ascend the Allegheny River after the flood, to Braeburn with two barges of rock to try to fill the gaping hole at the end of the dam.

March 22

The steamboat E.K. Davison brought four wooden barges to be sunk loaded with rock into the new water course. There were more than 100 men working at the site under the supervision of the Army Corps of Engineers.

March 23

The remainder of the brick office building belonging to Braeburn Steel was toppled into the Allegheny River to stop the erosion of the riverbank.

Present at the dam were the steamboat Pennova, two barges of rocks, two large derrick boats, a dredge boat, two quarter boats and a fleet of barges containing sandbags.

The steamer Elizabeth Smith was sent to attend to the derrick boats. Quarter boats were used to provide food and lodging for the men working at the site.

At the height of the work, more than 3,000 meals per day were being provided for the workers. Fleets of trucks were also needed to carry food and supplies to those working at the dam.

March 24

Two of the railroad side tracks had fallen into the river. The diesel tugboat Betty, with a barge filled with rock, and a quarter boat arrived in Braeburn.

In the afternoon, a large empty steel hopper railroad car was dumped into the river to attempt to protect the bank but it was swept away by the swift current downstream to Edgecliff, where it became lodged near the steamboat lanes.

Local residents describe other railroad cars filled with rock being dumped into the river which were not carried away by the current.

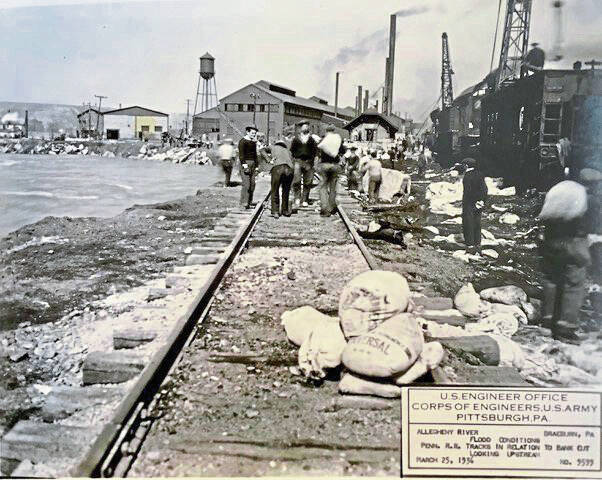

March 25

There were 500 men working at Braeburn to try and save Braeburn Steel and the tracks of the Pennsylvania Railroad.

The corner of a factory building at the mill became undermined by the flood waters. One of the largest fleets ever assembled on the Allegheny River was anchored at Braeburn.

The Army Corps of Engineers decided not to dynamite the dam. A long string of steel hopper cars filled with rock were being held on the threatened railroad tracks in case they would be needed to dump into the river to protect the railroad bed.

A fleet of wooden barges was also being held to be filled with rock and sunk in the channel should further erosion occur.

March 26

The steamship Elizabeth Smith sank in 15 feet of water in the channel between Jack’s Island and the mill. It was piloted by Captain William Cavett and had a crew of 13.

The hull was punctured by debris that had been entangled in its rudders. There were 700 men working continuous shifts fighting the flood and more than 100,000 sandbags had been used, along with hundreds of tons of rocks that had been dumped to protect the mill and railroad.

The Pennsylvania Railroad announced that it would send eight obsolete locomotives to be dumped into the river at Braeburn.

The tracks at Braeburn were of vital importance. They were part of the Conemaugh Division which ran from Pittsburgh to Buffalo, N.Y. All train traffic east of New Kensington had been halted.

March 27

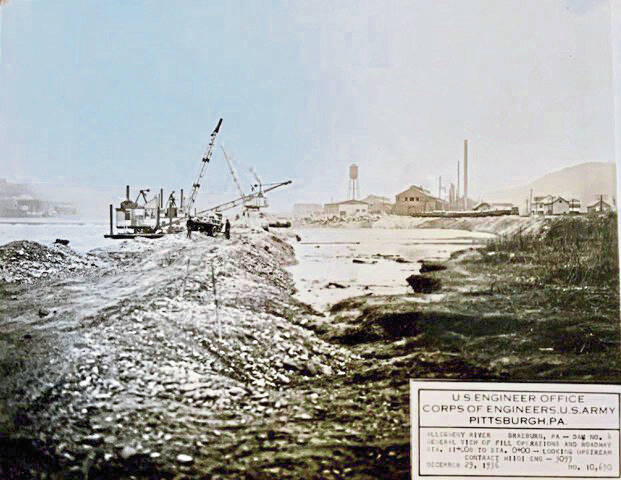

It was announced that the Army Corps of Engineers had gained the upper hand fighting the washout at Braeburn. They had used more than 900 men under the direction of 50 engineers.

More than 150,000 sandbags and hundreds of tons of rock had been used. They further announced that they had cancelled plans to use the old locomotives in the fill.

Since the St. Patrick’s Day Flood, the Army Corps of Engineers has built 16 dams and lakes in the Pittsburgh district, which includes the Alle-Kiski Valley, to control flood waters.