Editor’s note: Portions of a first-person account from Janice Steinhagen, formerly Janice Malego, appear in italics throughout this article.

Janice Steinhagen’s story based on an exclusive interview with former Iran hostage Jerry Miele sits in a box with 40 years’ worth of newspaper clippings.

But as a story, it looms large in her career and has had an outsize influence on the kind of journalist she became.

“I haven’t read it in a while,” she told the Tribune-Review. “It was probably the most intense three hours of my life. … He had to tell somebody.”

On the 40th anniversary of the start of the Iran hostage crisis, Steinhagen said she’s glad her then-editor at the Mt. Pleasant Journal, Leonard “Len” DeCarlo, gave her the assignment of a lifetime.

“He was adamant from the very beginning that we were not going to milk that story gratuitously. That was the reason (the Miele family) were kindly disposed to us,” said Steinhagen, 61, of Griswold, Conn.

On the day I was hired for my first job as a reporter, a cryptic two-inch-long story appeared on the front page of the paper that had hired me. The headline read “Local man held in Iran.” …

… Revolutionary extremists had stormed the American embassy in Tehran, taking 52 Americans hostage. One of them — a balding, bearded man whose blindfolded visage would soon emerge as the national icon of what became known as the hostage crisis — was Mount Pleasant native Jerry Miele.

Then a 41-year-old CIA communications specialist, Miele was swept up in the 444-day international incident that began on Nov. 4, 1979, at the end of Jimmy Carter’s presidency. He and 51 other employees of the U.S. embassy in Iran’s capital were taken hostage at gunpoint by militants just months after the Iranian revolution. The group of hostages also included another Western Pennsylvanian — Army Master Sgt. Regis Ragan, of Johnstown.

They were finally released on Jan. 20, 1981, the same day Ronald Reagan was inaugurated as president.

The hostages’ ordeal, but especially Miele’s captivity, for months became front-page news for the Journal. Steinhagen, then 23-year-old Janice Malego, joined the weekly newspaper staff after graduating from Seton Hill College with a degree in art education.

“I had not been trained as a journalist. I was flying by the seat of my pants,” she said.

As the crisis unfolded, the stories about it on our front page became longer and more ominous. As I sat at my desk, grappling with learning to write like a reporter instead of an essayist, I overheard colleagues on the phone with the State Department, trying to squeeze information on Jerry and the other hostages out of tight-lipped spokesmen.

Jerry’s blindfolded but identifiable face appeared every night on TV news, a visual shorthand for the ongoing political standoff. Our mayor, Bill Potoka, called rallies and prayer vigils for townspeople whenever some significant development occurred. Folks showed up en masse in our town square, the Diamond, wearing yellow ribbons (a reference to the popular song “Tie a Yellow Ribbon”) and waving American flags. …

… DeCarlo was adamant that we give the Mieles their privacy, not hound them for comments and quotes. “We have to live with these people after this is all over,” he told us.

As the crisis dragged on over a year and attrition took its toll on our newsroom, eventually it was me, the cub reporter, making the phone calls to the State Department. I summoned up all my acting skills to sound professional, as if I knew what I was doing. After a while, the act began to convince even me.

As the hostage crisis wore on, Steinhagen, a 1975 graduate of Geibel Catholic High School in Connellsville, became more involved with the Journal’s coverage. When the hostages’ release was announced, she was sent to the Miele family home to get comments from his mother and sister, a Catholic nun.

“She seemed to have developed a rapport with the family and was able to make regular updates on developments,” DeCarlo said. “The other stories that she had handled led me to believe she could handle that very well — and she did. … She did a super job.”

When the hostages were finally released, … I stood on the front porch of the Mieles’ little house, shaking in my shoes as I knocked on the door. Jerry’s mother answered, and as I explained who I was, she began closing the door in my face, just as I’d feared.

But then I heard a voice from inside: “It’s okay, Ma. It’s the Journal. They’ve been good to us. You can let her in.” Jerry’s mom gave me precious little in the way of quotes, but her daughter the nun filled in the blanks about their joy at the prospect of finally embracing Jerry again.

A week later, they opened the door to me again, this time to interview Jerry himself. This was an exclusive interview — they told me that he would only talk to the Journal. A more seasoned journalist would have been elated at scooping the Pittsburgh Press and WTAE-TV, but I was petrified.

“You’re a guy, Lenny,” I told my editor. “You’re his age. You were in Vietnam. He’ll be able to relate better to you.” But Len was adamant: “It’s your story, has been for some time now. You need to see it through.”

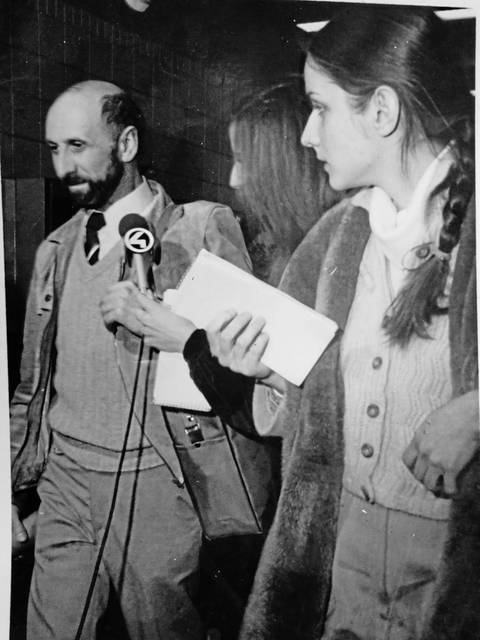

On the day that Miele arrived at Greater Pittsburgh International Airport, Steinhagen and DeCarlo were there to meet him. “It was just me and a reporter from WTAE-TV. I don’t think I got any questions in,” she said.

The next week, she was granted her exclusive interview, which she recalls lasted three hours. Most of what Miele told her he asked her not to print.

“He talked about what it was like in captivity, how he was treated. He felt his life was in danger. He told a really gripping story about the night that the failed rescue attempt took place (in April 1980),” she said. “That night he told about how they spirited everybody away. They took all the hostages and moved them under cover of darkness. None of them knew what was going on. They thought for sure they were going to be killed.

“It was edge-of-your-seat kind of stuff.”

What Miele didn’t say is something Steinhagen remembers most.

“It was one of those interviews where there were these long silences. He would say something and then fall silent for a long time,” she said. “I almost didn’t know what to ask him because what he experienced was so far outside my own experience.”

He’d been a communications officer at the embassy, and the terrorists had come upon him shredding documents. Because of that, they were harder on him. More than once, he was convinced that he was moments from getting killed. At times, he wanted to die. I got the feeling that he was telling me things he couldn’t tell his family just yet.

He told me he dreaded the massive welcome-home parade Mayor Potoka was planning. He just wanted to get back to his own quiet life and work. But, like us, he still had to live with these people. The townspeople had rallied to support his family, so the least he could do was show up at their celebration of his release.

So, on a frigid February day, Jerry braved the nine-degree weather and stood on the podium at the Diamond with the mayor, the governor, an array of dignitaries and thousands of onlookers. He smiled politely through the speeches and offered a handful of words of thanks himself before the hour-long parade got underway. Mount Pleasant was awash with yellow ribbons and euphoria. Our banner headline that week read “Nine degrees, but the town’s warmest day.”

That was in January 1981. By August of that year, Steinhagen was newly married and in the process of moving to Connecticut. Her journalism career has mostly focused on local news. In June, she retired from Courant Community, a weekly newspaper published by the Hartford Courant.

Steinhagen learned from the Miele story the importance of the human scale in every story, even those with a national or international scope.

And she got a lesson in respecting people’s privacy while still keeping the public informed.

“The most recurring theme was a sense of trust,” she said. “The knowledge that people are trusting you with is important, but it’s just as important that you do justice to your story and to your readers.”

Miele declined a request for an interview. For the 25th anniversary of the ordeal, he told the Tribune-Review: “I was never afraid to die, but I was afraid of being tortured.”

The quiet man had only been in Iran from roughly Valentine’s Day to Halloween before becoming the face of an international crisis.

“I didn’t think I was going to make it,” he said in 2004.

Jerry retired back home to Mount Pleasant after his State Department career ended. My brother tells me he bumps into him periodically, at the bank or the post office. I imagine he’s grateful that in the four decades since, it’s been my name, not his, appearing in the paper on a regular basis.