Coal mining’s roots in the Pittsburgh area run deeper than the foundations of American democracy.

Since the mid-1700s, years before the Declaration of Independence, Pennsylvanians have mined 250,000 acres of land for coal, pulling more than 15 billion tons of the fossil fuel from the earth, according to the state Department of Environmental Protection.

That Pennsylvania coal provided warmth and light in American homes. It also fueled an industrial boom that triggered technological advances and war-time victories, and crowned the U.S. as a world superpower.

But, today, that mining has hollowed out the ground beneath us.

Pennsylvania’s inventory of abandoned coal mines is larger than that of any other state in the nation, and the Keystone State has received billions of dollars in government funding to ensure what the mining legacy left behind doesn’t pose public health or safety threats.

President Joe Biden’s administration has funneled about $740 million to Pennsylvania in the past three years alone to help keep abandoned mines safe — often by filling large, vacant chasms with gravel and cement.

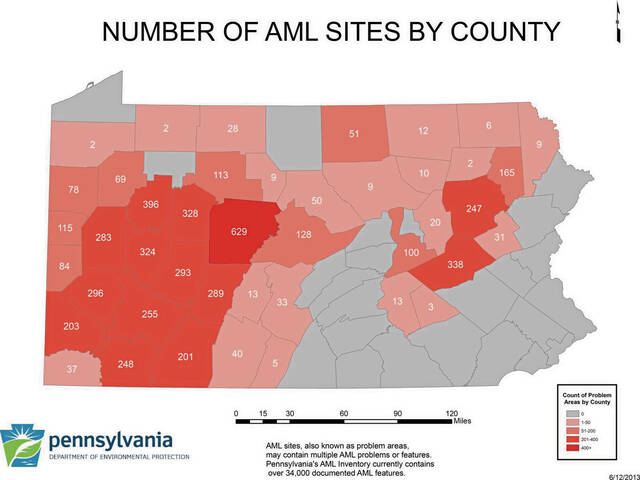

There are at least 550 abandoned mine sites in Allegheny and Westmoreland counties combined, according to the Department of Environmental Protection.

Clearfield County has 629 sites; Greene County, which boasts the smallest number in the Pittsburgh area, has 37.

Despite efforts to shore up or develop those sites, one state agency has responded to nearly 600 mine subsidence emergencies — incidents involving ground movement following underground mining — since 2017.

The search-and-rescue effort launched early last week after a woman fell into a sinkhole in Unity is one of at least 75 incidents the DEP has responded to this year. Hundreds of first responders worked the scene. After more than 80 hours of searching and excavating, the body of Elizabeth Pollard, 64, of Unity was recovered Friday afternoon.

“These coal-patch towns have loads of mines. Every town has a mine underneath it,” said Crabtree fire Chief Bill Watkins, who responded to the sinkhole in Unity. “Definitely, down the road, you’re going to see more of this.”

A driveway to nowhere

Carole Mullen awoke to a nightmare on Jan. 13, 2017.

After getting out of bed about 7 a.m., she couldn’t get out of her bedroom.

Mullen’s daughter Bonnie Levay helped wrest open the bedroom door. Then the pair quickly realized something was askew with the Latrobe home.

The hallway appeared slanted, giving Mullen a sense of vertigo as she walked. A sliding glass door nearby appeared crooked on its rails. First responders, dispatched after the family called 911, worked to free Mullen and her four grandchildren from the home.

Latrobe fire Chief John Brasile said mine subsidence in a tight-knit residential area of the city’s Lloydsville neighborhood had warped the house’s foundation. The city condemned the home days later.

Today, all that remains on the Eleanor Drive lot is a driveway leading nowhere.

Mullen, who owned and operated DeCaro’s Deli in Latrobe, first heard Elizabeth Pollard’s name on the TV news last Monday. She instantly felt a kinship with Pollard.

“I’ve just been absolutely sick with what’s happened with Ms. Pollard — I can’t even imagine what her family is going through,” Mullen, 60, told TribLive. “But we just have these mines everywhere.”

DEP doesn’t appear to track the number of injuries or deaths that mine subsidence causes in Pennsylvania. Spokeswoman Lauren Camarda has worked for DEP for eight years. She never has heard of a single one.

“This was obviously an unexpected and pretty rare tragedy,” said Anne Daymut, a watershed coordinator with a nonprofit serving 24 counties in Western Pennsylvania’s coal country. “In the eastern half of the U.S., we don’t see human deaths as a result of subsidence. It usually involves homes and structures.”

But Daymut and others working in the field worry that incidents like the one in Unity could become more common.

“Eventually, that (mine) is going to collapse,” Daymut said. “We are just now starting to see the effects of abandoned mines and subsidence issues.”

“And I think it’s going to get worse.”

Toll of abandoned mines

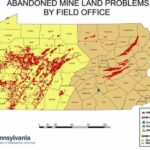

Abandoned mines are a major problem in Pennsylvania, involving a number of players.

Experts say it could cost $5 billion to safeguard Pennsylvanians’ homes and workplaces from mine subsidence, toxic water discharges and related problems.

DEP said federal funding has enabled it to rehabilitate 91,000 acres of abandoned mine lines. That often involves filling “voids” — the term officials use to describe unknown spaces left behind in abandoned mines — with gravel or cement.

Discharge from these abandoned sites also is a problem, experts told TribLive.

Water traveling through the mines usually is highly acidic and contains heavy metals such as aluminum and iron, which Daymut said can destroy food for fish and, accordingly, warp an ecosystem.

Common ways to fight the toxic discharges affecting an estimated 5,500 miles of streams in Pennsylvania include chemical treatment and water filtration.

In April, Lt. Gov. Austin Davis and Deb Haaland, who heads the U.S. Department of the Interior, trekked to Westmoreland County to tout the federal government’s investment of $725 million designated to clean up abandoned mines.

Pennsylvania received $244 million of that funding this year — nearly a third of the nationwide total.

“This is a real problem in Pennsylvania, one the Biden administration and the commonwealth are focused on addressing,” Gov. Josh Shapiro said at the time.

“Pennsylvania has a long history of surface and underground mining, and its effects can still be seen across much of the commonwealth,” DEP’s Camarda added. “While DEP has made strides inventorying these abandoned mine land features, digitizing maps and completing projects … the need far outpaces the resources available.”

In October of last year, subsidence from a mine shuttered in 1906 damaged a Veterans of Foreign Wars hall and at least seven homes in Pittsburgh’s Lincoln Place neighborhood. The abandoned mine, which sat about 140 feet below the homes, created large cracks in the buildings’ walls that could be seen from the street.

Weeks earlier, on Sept. 16, 2023, DEP found that an abandoned mine in Washington Township, Fayette County, had damaged basements in six nearby homes.

For Watkins, the fire chief, a flash point for mine subsidence hit Hempfield in May 2022.

Two firefighters rappelled into a mine shaft after a man fell 25 feet through a 2- to 3-foot opening in the backyard of a home on Tipple Row Road in Hempfield’s Luxor neighborhood.

Less than 40 minutes after the incident was called in to 911, rescuers had pulled the man, who has autism and was nonverbal, out of the shaft. He suffered only “bumps and bruises.”

“We had a visual on him the whole time — we had better structural integrity there than they did in Unity,” Watkins said Friday.

Watkins, 51, a lifelong Crabtree resident who has led the volunteer fire department for more than 20 years, said he sees mine subsidence all over. Soil around his home’s foundation has shifted about 2 inches since he moved there in 2004.

“Honestly, Crabtree, these coal-patch towns? On any given day, something could cut loose,” he said.

State officials are trying to get ahead of the curve.

In one project, DEP plans to spend $10.5 million to pour thousands of cubic yards of grout into abandoned mines sitting under a 50-block area in North Belle Vernon, Westmoreland County, and adjoining Belle Vernon, Fayette County.

About 230 homes are affected.

Spending on mines

As vacant as they sound, abandoned mines are touched by many hands — from government agencies to nonprofit groups to environmental advocates, experts say.

The Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement, which sits under the Interior Department, plans spend more than $300 million in fiscal 2025 — more than half of it on abandoned mine work.

Since 2016, the department has allocated more than $1 billion to support communities affected by abandoned mines, though less than a third of that has been spent, according to the U.S. Government Accountability Office.

More than $175 million of the Interior money was earmarked for work in Pennsylvania.

The Department of Agriculture spends millions on projects in rural areas with abandoned mines. Pennsylvania received nearly $29 million of that funding this year.

It’s unclear how much the Environmental Protection Agency, whose 2024 budget topped $12 billion, spent this year to regulate pollution from abandoned mines on federal land. The agency said EPA officials were unable to speak last week with a TribLive reporter.

Academia also contributes to the efforts to repair the damage left behind by widespread coal mining.

Sanjay Srinivasan started teaching at Penn State University as the Marcellus shale industry blossomed in Pennsylvania in the early 2000s. Although Marcellus shale continues to grab headlines, Penn State’s roots run deeper with coal mining, Srinivasan said.

The university established its mining engineering department in 1890 and remains one of just 14 schools in the U.S. to offer accredited courses in the subject.

In recent years, Penn State has helped lead technological innovations in addressing the safety of abandoned mines, the professor said.

Researchers helped government officials complete digital and GIS mapping of abandoned mines, Srinivasan said. They also have tested ways of using satellite imagery to gauge ground instability near former mine operations.

Companies tapping into the Marcellus shale can learn lessons from what abandoned mines left behind, Srinivasan said.

But, he stressed, the historical benefits of coal mining in Pennsylvania outweigh contemporary concerns or costs.

“It’s an enormous amount of money we are spending (on abandoned mines) but not very significant if you can consider the technological advances coal produced over centuries,” Srinivasan told TribLive.

“We did a lot of mining, and we extracted a lot of coal — and that helped our country get to the point where we are right now,” he added. “And we have to pay tribute to what it did for our country and our society at that time.”