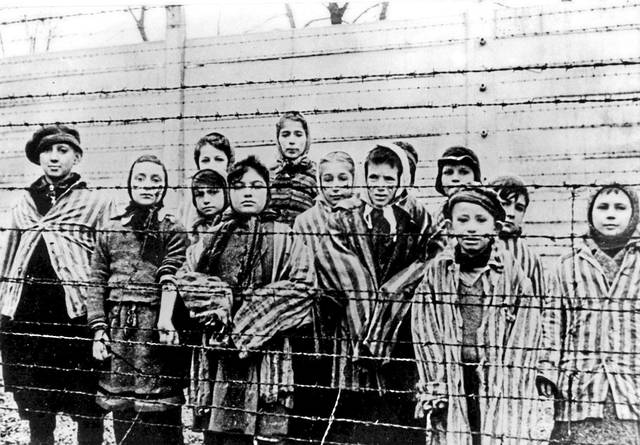

Steven Fenves and his family were swept up from their Yugoslavian home during World War II, when they were split up and forced into ghettos, then German concentration camps. That included Auschwitz, where his grandmother and then his mother died, caught in the Nazi death machine that slaughtered an estimated 6 million Jews across Europe.

For the 88-year-old Fenves and other Holocaust survivors, as well as families of those who survived and those who did not, accessing records about the Nazi state’s unconscionable stain on humanity has become easier and richer with new public access to millions of records — some available online — over the past year.

“The more information about the Holocaust, the better it is that we know what happened — and the better we can help prevent it from happening again,” said Fenves, a distinguished professor of civil engineering at Carnegie Mellon University who retired to Rockville, Md.

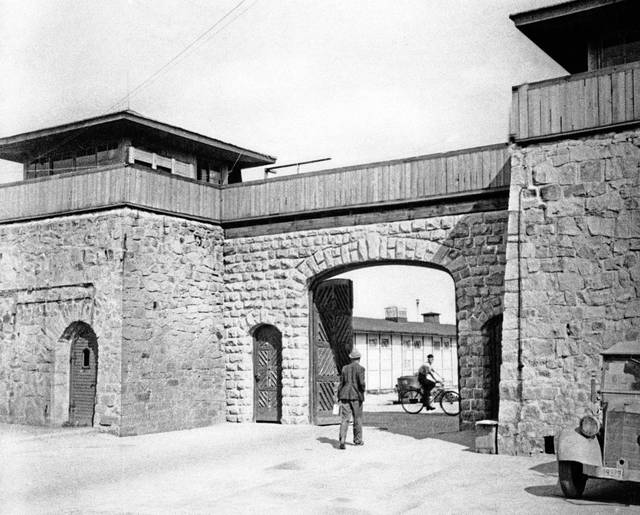

Monday marks the 75th anniversary of the day Russian troops liberated the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp and extermination center in Southern Poland, where the Germans killed between 1.1 million and 1.5 million people. It was the deadliest of the Nazi death camps. Anniversaries for scores of other camp liberations will follow in the months ahead.

“I expect that the 75th anniversary of liberation will drive renewed interest in the Holocaust and, with it, increased research in online archives,” said Lauren Apter Bairnsfather, director of the Holocaust Center of Pittsburgh.

Expanded access

An estimated 13 million Holocaust-related documents were placed online last year by the Arolsen Archives/International Center for Nazi Persecution. The German center, formerly known as the International Tracing Service, has 30 million documents in its collection, many of which were discovered in Nazi concentration camps. Records from camps and ghettos are online, as are documents related to death marches.

“Before the (Arolsen) archives were digitized, very few had the opportunity to go through the archives,” Bairnsfather said. “Now, people can do it easily. It really … ties information that is available to something that happened to their relatives 75 years ago.”

Since November, researchers have had online access to 850,000 documents pertaining to about 10 million people that the United States collected in its post-war occupation zone, according to the Arolsen Archives. The American Zone in Southern Germany was the largest occupation zone of the four Allied powers — the United States, Great Britain, France and the Soviet Union. The center said it plans to focus next on digitizing the records from the British Occupation Zone in Northern Germany.

In July, Arolsen Archives and Ancestry announced a partnership to create the Holocaust Remembrance Collection on ancestry.com. The genealogical research site has allowed searches of its Holocaust-related records for free to people worldwide. Those include passenger lists of ships that carried displaced persons after the war to new homes in the United States, Israel and elsewhere. It also allows online access to registers of people living in Germany who were persecuted by public institutions and corporations. Some of these records include details on those who died and where they were buried, according to Ancestry.com.

The U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., is designated as the national repository for the Arolsen Archives collection in the United States. Since gaining access to the archives in 2007, the museum has received about 35,000 requests — 22,100 of which are from Holocaust survivors or their families, said Raymund Flandez, a museum spokesman.

“The requests for information have been constant year after year,” Flandez said.

The museum opened in 1993. In 2018, about 45 million people visited in person while another 15 million people worldwide accessed its online Holocaust Encyclopedia, which is available in 16 languages. In February, new discoveries in that research project will be presented at Rodef Shalom Congregation in Pittsburgh.

Last fall, the museum received a newly digitized collection of evidence from the post-World War II Nazi war crime trials held in Nuremberg. The collection, from the International Court of Justice in the Netherlands, includes photos and films along with 250,000 pages of documents and 775 hours of proceeding recordings, according to The Washington Post.

A duplicate copy was sent to Mémorial de la Shoah, the French Holocaust museum in Paris.

Researchers can hear testimony of survivors who recounted the horrors they experienced in the death camps. The U.S. museum also has online links to the testimony at the war trials, including the trial of Nazi murder mastermind Adolf Eichmann.

Fenves was 13 and living in Yugoslavia in June 1944 when he and his family were rounded up. His father was sent to Auschwitz-Birkenau. Fenves, his sister, their mother and grandmother went to a Jewish ghetto. They later were transported by rail in cattle cars to Auschwitz. He ended up in the camp at Buchenwald, where he was liberated.

His sister also survived, and they were briefly reunited with their father. He died within a few months.

Through the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, where he volunteers, Fenves has accessed transportation records of the Buchenwald camp along with punishment records and punch cards containing information about the camps.

“It’s much easier now to trace those records than going to (Germany),” Fenves said.

A former family cook got into the family’s house in Subotica, Yugoslavia, before looters ransacked it. The cook gathered his mother’s cookbook, her diary and some of her artwork. Fenves and his sister retrieved the items after the war, one piece of which he has since donated to the Holocaust museum.

“They just digitized my mother’s cookbook,” Fenves said.

More records coming

The Roman Catholic Church soon will open more of its records to Holocaust researchers.

Beginning March 2, scholars are set to arrive in Rome to examine the Vatican Apostolic Archives of Pope Pius XII. Materials from 1939 to 1958 will be available related to Pope Pius XII, who has been criticized for not doing enough to help save European Jews. The American Jewish Committee has sought for 30 years to have access to records showing what the Catholic Church did during the Holocaust.

A group of 65 researchers — 10 from the United States, including two from the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum — has been approved to view the records in person, the Vatican has said.

James Paharik, director of Seton Hill University’s National Catholic Center for Holocaust Education, said he does not know if the Greensburg center will gain any online access to the Vatican records.

The center’s library has a collection of Holocaust-related materials, primarily intended to help students understand the atrocity. The university’s library also has a collection that is publicly available, Paharik noted.

“It’s important to have access to such an event in human history — the mechanized, industrialized killing like the Holocaust,” said Franklin Harvey of Derry, an adjunct professor who teaches world religion at Westmoreland County Community College.

Harvey attended an education conference in 2018 at the Holocaust Memorial Museum designed to engage and promote students’ understanding of the Holocaust. He plans to attend a Holocaust education seminar this summer at Yad Vashem, the World Holocaust Remembrance Center, in Jerusalem.

“We want to teach about it, so we never forget about it and it doesn’t happen again,” Harvey said.

The volume of material available is staggering to some.

There is so much information available to people searching for Holocaust records that it can be overwhelming, said Joel Last, a Greensburg psychiatrist who is the son of Holocaust survivors.

Much of his knowledge of his parents’ plight came from relatives of his generation. Marcus and Paula Last, who escaped after Germans slaughtered many in their Eastern Poland village, rarely spoke of their experiences, their son said. The couple did not know each other during the war, only meeting afterward in Austria as displaced persons.

“There is no shortage of documents,” Last said. “How do you digitize it all? There is so much … it is painful to actually study.”

Having online access to records will make it easier for future generations to study the Holocaust, long after the remaining survivors and liberators have passed, Bairnsfather said. She estimated only about 50 Holocaust survivors remain in the Pittsburgh region.

“It is absolutely important. A lot of people don’t know about it,” Bairnsfather said. “A lot don’t believe it happened — the most extreme case of anti-Semitism.”