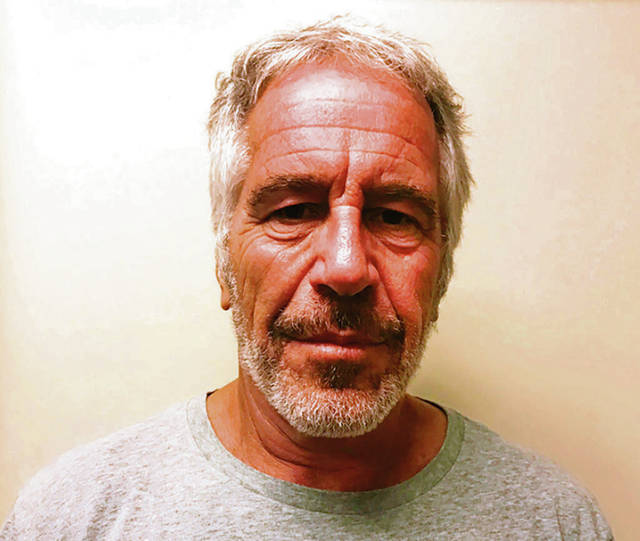

Fallout from the teen sex trafficking scandal of the late Jeffrey Epstein, a wealthy financier and convicted pedophile who hanged himself in a New York City jail cell, continues to plow a path of destruction.

Manhattan jail guards face federal criminal charges related to Epstein’s death and an alleged subsequent cover-up.

Britain’s Prince Andrew has been toppled from grace and stripped of his royal duties since an American woman publicly alleged that Epstein brought her to London, where she was forced to have sex with the Duke of York — when she was 17.

More than 20 women have sued Epstein’s estate, claiming he targeted them for sex as early as 1985, when the youngest of the alleged victims was just 13. Nine accusers — identified in court documents as Jane Doe I through Jane Doe IX — filed lawsuits this month.

An Irwin native began investigating Epstein years ago, long before the billionaire playboy was jailed to await trial on charges of sex trafficking in underage girls. When Epstein, 66, killed himself in August, he again robbed victims of a chance to heal and get justice, said Michael Reiter, who grew up in Westmoreland County and later served as police chief in Palm Beach, Fla.

“Seeing Epstein in person in handcuffs and prisoner apparel, or seeing him in court being sentenced to life in prison, would be therapeutic for some victims in a way that hearing reports of his death is not,” Reiter said.

His department investigated sex crime allegations against Epstein a decade and a half ago. Had prosecutors been more aggressive, more girls could have been protected, Reiter said.

“Epstein was one of the more prolific sex offenders of our time,” he said.

Early case

Palm Beach police investigated sexual assault allegations against Epstein as early as March 2005.

A woman told police her 14-year-old daughter had sexual relations “with a man named Jeff” who lived in a Palm Beach mansion. Detectives soon discovered “Jeff” was Epstein.

The more they investigated, the more they discovered additional underage girls who claimed to have had sexual relations with Epstein, said Reiter, 62, who still lives in Palm Beach, where he served as police chief from 2001-09 after rising through department ranks. Investigators rooted through Epstein’s trash, gathering notes related to the girls, staked out his house and interviewed alleged victims along with Epstein employees, records show.

“It was completely clear that he was offending hundreds, if not thousands, of girls. It was so clear, so obvious,” Reiter said. “(The girls) looked like children.”

The case detectives built against Epstein was strong, Reiter said. He wanted serious charges filed, which would have brought a long prison sentence with a conviction.

“We had to stop him,” Reiter said. “Prosecution on our charges should have resulted in a life sentence for Epstein.”

Prosecutors in Palm Beach County, however, were not as convinced.

“The state attorney simply wanted Epstein charged with a misdemeanor count of lewd and lascivious molestation,” Reiter said.

Realizing the state attorney’s office did not view the case as seriously as he did, Reiter asked the top prosecutor to remove himself and have the governor assign a replacement. The state attorney declined and ultimately presented just one victim to a grand jury, which indicted Epstein on a single felony charge in 2008.

“We had about a dozen cooperating victims, numerous fact witnesses and over a hundred counts of sex crimes,” Reiter said.

In 2007, he turned to R. Alexander Acosta, who then served as U.S. Attorney for Southern Florida, to get him to assume control of the investigation. (President Trump in 2017 tapped Acosta to serve as U.S. Secretary of Labor.)

FBI records indicate that Palm Beach police conducted a sexual battery investigation into Epstein from March 2005 through February 2006. In July that year, federal agents opened a child prostitution investigation into Epstein and others, issuing subpoenas — including through the help of the FBI office in New York City — for witnesses to appear before a grand jury, records show.

Investigators and prosecutors drafted a 53-page indictment to charge Epstein as a sexual predator.

Instead of filing it, however, Acosta brokered a deal in June 2008 that shielded Epstein from federal prosecution and instead had him plead guilty in a Florida state court to felony child prostitution charges. He served 13 months in jail — with a sweetheart work-release program and allowances to travel often to New York and his private island in the Caribbean.

After New York prosecutors in July 2019 charged Epstein with child sex crimes, Acosta publicly defended his actions, saying that he took the case from Florida prosecutors who were willing to let Epstein plead to a lesser charge. Scrutiny from Congressional Democrats over that deal led Acosta to resign as head of the labor department.

Pushing for justice

Reiter said it was obvious to him that Epstein’s wealth and influence provided him with the best defense lawyers and paved the way to a sweetheart deal from prosecutors.

Before the first victim came forward, Epstein paid for equipment for the Palm Beach police department and funded other government initiatives, Reiter said. But the donation was returned after Epstein was charged.

“Defense attorneys (for Epstein) persuaded local prosecutors that this case was not as serious or prosecutable as we saw it and that the sex was consensual. That had no bearing on the case, since under Florida law, minors can never provide legal consent for sex with an adult,” Reiter said.

Julie K. Brown, an investigative reporter for the Miami Herald, extensively covered the Epstein case. She credited Reiter for his dogged pursuit.

“There were only two people who risked their careers on this investigation — Mike Reiter and Joe Recarey,” Brown said. Recarey, who died in May 2018, was the lead detective in the Epstein case for the Palm Beach Police Department.

“There were so many people that really ignored the good evidence. It was very strong evidence,” Brown said.

Epstein’s high-priced legal defense team managed to convince prosecutors that the girls were prostitutes “coming from the wrong side of the tracks” and were not to be believed, even though investigators had phone records and the girls’ statements to back up the evidence.

“How do you get about 36 girls to give the same story?” Brown said. The majority of the girls were from the same high school, but the school was so big that everyone did not know each other. The girls told friends about Epstein and “recruited” them to go to his mansion, Brown said.

Epstein’s lawyers engineered legal maneuvers that made it impossible to bring the case to trial, she said. “They were going for a plea deal, to make (the case) go away.”

Irwin roots

Reiter grew up in Irwin’s Penglyn neighborhood and graduated from Norwin High School in 1975. His late mother, Elizabeth Rose Reiter, was the sister of Irwin mayor Daniel T. Rose, who served from 1986 to 2015, the year he died.

“My father (the late Raymond Reiter) and my Uncle Dan Rose modeled a sense of duty and honor that has served as an example for me to follow,” Reiter said. Both men were pilots who flew bombing missions in Europe during World War II.

“Those principles guided me through this difficult case and continue to inspire me every day,” Reiter said.

He studied criminal justice at Penn State’s McKeesport campus and worked as a campus police officer for the University of Pittsburgh. He also had an internship with the North Huntingdon Police Department while studying at Penn State. He later attended the FBI National Academy and did post-graduate study at Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government.

One of the main reasons Reiter went through the municipal police academy and became a cop was that his cousin, Daniel Rose, was a seasonal police officer in Ocean City, Md.

“We grew up living next door to each other,” Reiter said.

Rose recalled how Reiter became enthralled with being a police officer, while working for Ocean City in another capacity.

After leaving the job at Ocean City, Rose worked in Braddock and later with Reiter at Pitt.

In the midst of another Western Pennsylvania winter in January 1981, Reiter saw an opportunity to move south to a warmer climate when he learned Palm Beach was looking for police officers. Even though the job paid $2,000 less than he was making, he jumped at the chance.

“He (Reiter) was a dedicated officer,” said Rose, who owns a swimming pool business in North Huntingdon.

Six months after Epstein pleaded guilty, Reiter retired — after serving 28 years with the Palm Beach department.

“I had to get through the Epstein case,” Reiter said.

Today, Reiter operates his own security and investigative firm in Palm Beach, advising large venues and wealthy families. But he remains tied to the Epstein case.

Rose is convinced that Reiter’s upbringing in the small Western Pennsylvania town provided him with the moral underpinning to pursue the investigation against the wealthy Epstein when others might have turned away.

“If it had not been for someone of Mike’s character, from a small town, (the investigation into Epstein) never would have happened,” Rose said.