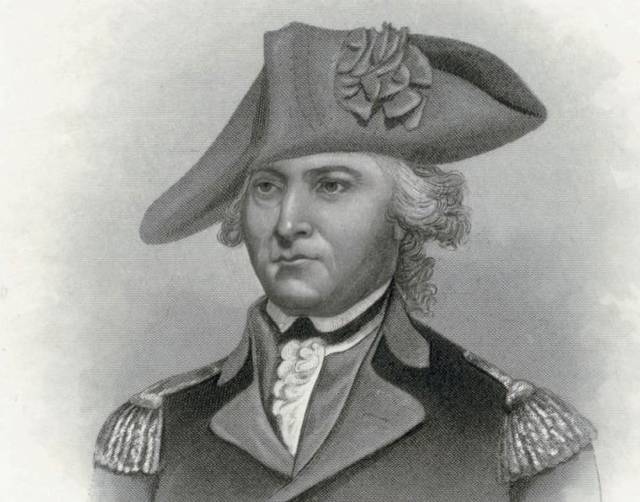

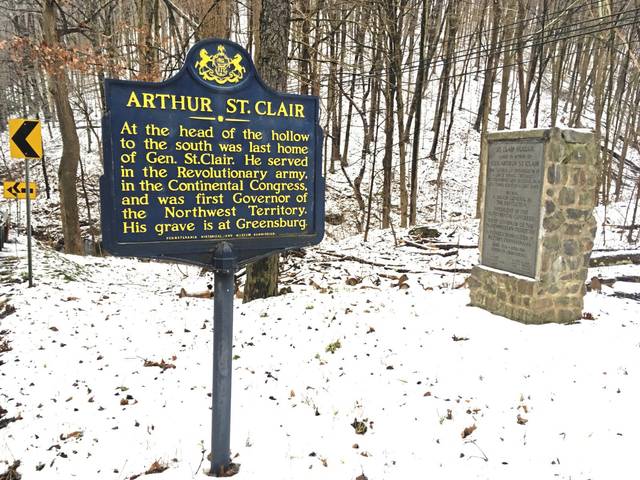

Local historians are familiar with the prominent roles Gen. Arthur St. Clair played in the early years of Westmoreland County, but many feel he hasn’t received the credit he’s due for his contributions on a national stage.

Caretaker of the decommissioned Fort Ligonier in the late 1760s, St. Clair served as justice for the area that would become Westmoreland and was the first prothonotary and clerk of courts when Westmoreland was carved out of Bedford County in 1773.

Perhaps less well known is the fact that the former British officer advanced from colonel to major-general while serving the American cause in the Revolutionary War — the only Pennsylvania resident to attain that rank in the war. Or that, as president of the Continental Congress in 1787, he preceded George Washington as head of the new American government.

He then served as governor of the Northwest Territory — including the current states of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan and parts of Wisconsin and Minnesota. But his fortunes took a downward turn when his army was routed by opposing Native American forces in the 1791 Battle of Wabash River.

St. Clair’s origins in Scotland have been the most obscure of all. But Susan Sommers, a history professor at Saint Vincent College, author and outgoing chair of the Westmoreland County Historical Society, plans to fill in some of those gaps Feb. 5 when she presents the annual St. Clair Lecture on the Pitt-Greensburg campus. Titled “Arthur St. Clair: Myth and History,” the talk will begin at 7 p.m. in Ferguson Theater, Smith Hall.

With the many documents that now exist online, archival research she completed in Edinburgh and having prepared an entry on St. Clair for a French volume on Freemasons, Sommers has compiled a more fact-based account of St. Clair’s formative years in Scotland than was reflected in an 1880s biographical sketch.

That 19th-century account relied heavily on “poems, legends, hearsay and family lore,” Sommers said. “Americans at that time were less concerned with factual evidence than with setting a heroic example.”

Those who attend Sommers’ lecture will learn about a criminal episode that occurred early in St. Clair’s life.

“If he ever went back to Scotland, there were grounds for hanging him,” she said. “It was not anything we’d hang him for today. He did not murder anybody.

“He wrote a letter home excusing himself. He was writing from Maryland, where he was beyond the long arm of the law.”

As for his choice of a career in the military, Sommers said it was logical for St. Clair, given the modest circumstances of his upbringing in a family of merchants in Thurso, Scotland.

“His whole career shows he was a very ambitious fellow,” she said. “He was from way up north, almost to the Orkneys. It was very sparsely populated and very poor. If he didn’t want to spend his life selling fish, there wasn’t a lot else to do.”

In 1757, when he was in his early 20s, St. Clair was posted to America, where he served in the French and Indian War.

Sommers also has delved into St. Clair’s activities in Massachusetts, before his May 14, 1760, marriage to Phoebe Bayard of Boston, daughter of the colony’s governor. That marriage came with advantages, including access to sizable funds. But there also were challenges, Sommers said, noting that St. Clair’s letters hinted at illnesses his wife suffered.

“George Washington let him go home to take care of his wife a couple of times during the Revolutionary War,” Sommers said.

Through her research into some aspects of St. Clair’s life, Sommers has learned that “there’s a lot more to be discovered,” such as “his relationship with land speculation. He was clearly doing something with the land that was not making it pay.”

Sommers’ lecture is free and open to the public. Those planning to attend are asked to call 724-836-7980 by Feb. 1 to reserve a seat.

Jeff Himler is a Tribune-Review staff writer. You can contact Jeff at 724-836-6622, jhimler@tribweb.com or via Twitter @jhimler_news.