(Editor’s note: This is part of an ongoing series marking the 250th anniversary of Westmoreland County’s founding.)

Signs of one of Westmoreland County’s 18th century founding fathers still can be viewed by those who know where to look.

A township in the northeastern corner of the county was named for original Westmoreland government official and Revolutionary War officer Maj. Gen. Arthur St. Clair. His name also has become associated with a park along Greensburg’s Maple Avenue, where he and his wife, Phoebe, rest beneath a granite monument.

But the story behind the name — St. Clair’s importance to the young county, state and country he served — may not be as apparent to those who focus on such leading figures of the time as George Washington.

A native of Scotland who settled in the Ligonier area, St. Clair can claim to have headed the fledgling American government before Washington took on the role of president in April 1789. St. Clair served as president of the Continental Congress in 1787 and the following year was named governor of the Northwest Territory — including the states of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois. Michigan and parts of Wisconsin and Minnesota.

“It’s just amazing how influential (St. Clair) was to the region and how little there is left of his existence here,” said Brian Robb, a seventh-generation descendant. “He is arguably the most significant resident in the history of Westmoreland County.”

Robb splits his time between Ypsilanti, Mich., where he moved to work as an auto engineer, and the local home near Acme where he was raised.

When the covid-19 pandemic hit in 2020, he became more interested in investigating his family genealogy. With the help of archivist Shirley Iscrupe, in the Ligonier Valley Library’s Pennsylvania Room, he researched his St. Clair lineage, which descends from the general through his daughter, Louisa, and her husband, Samuel Robb.

“It’s very exciting that (Arthur St. Clair) is only one step removed from the Robb family name,” he said. “It’s a very direct connection.”

Samuel Robb was born in 1773, the same year Arthur St. Clair helped get the newly formed Westmoreland County off the ground. Louisa St. Clair was born two years earlier.

St. Clair already had served with the British army in the French and Indian War and was assigned as civil caretaker of the Fort Ligonier outpost after it was decommissioned in 1766, following that war. According to Matt Gault, director of education at the reconstructed Fort Ligonier, St. Clair constructed a home and gristmill near the former fort.

In 1770, St. Clair was appointed surveyor of Western Pennsylvania lands on behalf of the colony’s founding Penn family. Three years later, when Westmoreland County was formed from Bedford County, St. Clair served the new political subdivision in multiple roles: prothonotary, clerk, register and recorder. He also sat as a justice of the first English court west of the Allegheny Mountains.

Formation of Westmoreland was desired by local residents, who no longer wanted to travel over the Alleghenies to conduct legal matters in Bedford. Some also saw creation of the new county as a tactic in Pennsylvania’s efforts to block Virginia’s claim to areas west of the Monongahela River, which initially were part of Westmoreland.

St. Clair was among Pennsylvania proponents who contended with a rival local government Virginia officials operated for a time out of Pittsburgh.

As noted in “The Planting of Civilization in Western Pennsylvania,” a 1939 volume by Solon J. Buck and Elizabeth Hawthorn Buck, St. Clair helped organize a company of about 100 rangers in 1774 to help protect Westmoreland County’s northern frontier from incursions by Native American foes.

He also joined other Westmoreland magistrates in an attempt to prevent formation of a Virginia-backed militia at Pittsburgh.

When nemesis John Connolly proclaimed his appointment by Virginia’s governor as commandant at Fort Pitt, St. Clair had him arrested and confined in the jail at the county’s first official seat — Hanna’s Town in Hempfield.

The following year, St. Clair took custody of Connolly at Ligonier when the “commandant” again was arrested, on a charge of disloyalty to the colonies. But, in each case, St. Clair ultimately backed down to opposition by the Virginia camp, and Connolly was freed.

St. Clair’s remaining military career was uneven. In the Revolutionary War, he was promoted to brigadier general, and then major general, following Colonial victories at Quebec and Princeton, N.J. He also surrendered Fort Ticonderoga to British forces in July 1777, but he was acquitted of any blame in a subsequent court martial.

During his term as governor of the Northwest Territory, from 1787 to 1802, St. Clair expressed sympathy for Native Americans as the U.S. government sought treaties that swept the earlier inhabitants out of the way of white settlement.

St. Clair wrote to Secretary of War Henry Knox: “Though we hear much of the injuries and depredations that are committed by the Indians upon the whites, there is too much reason to believe that at least equal if not greater injuries are done to the Indians by the frontier settlers, of which we hear very little.”

Ultimately, St. Clair led American forces against those same native people and suffered a disastrous defeat at their hands that claimed 630 of his troops and resulted in him being stripped of his rank.

When he returned to civilian life, St. Clair found debts catching up with him. By 1809, Gault said, the former general had to auction off his home, “The Hermitage,” along modern Route 711 north of Ligonier. The property had an estimated value of $50,000 but sold for just $4,000.

Pittsburgh businessman James O’Hara took over St. Clair’s Hermitage iron furnace near Ligonier as payment of a debt.

He retreated with his family to a log tavern atop Chestnut Ridge. On Aug. 30, 1818, he took the reins of a wagon for a routine trip down the west side of the ridge to Youngstown, Gault said, but he was thrown from the wagon, was knocked unconscious and died the following day.

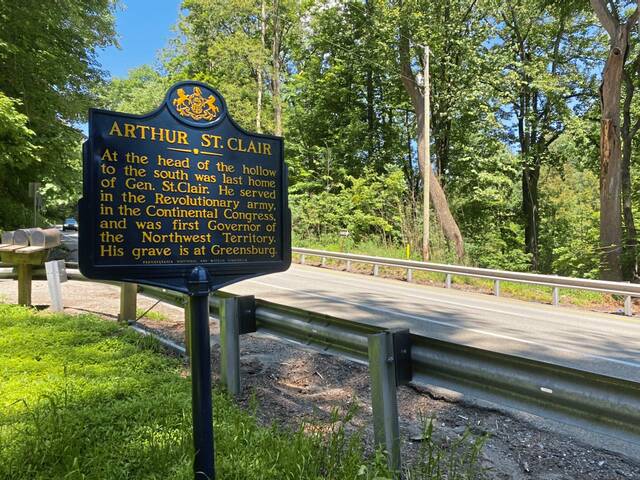

The parlor of The Hermitage has been moved to the museum at Fort Ligonier and has been restored with furnishings from the period when it was occupied by St. Clair. A state historical marker and a locally sponsored plaque referring to St. Clair’s later ridgetop home can be seen at St. Clair Hollow, along the eastbound lanes of Route 30 approaching the former Sleepy Hollow restaurant.

Robb faults federal officials, particularly the administration of Thomas Jefferson, for failing to properly reimburse his forebear for his services in the Revolutionary War and the Northwest Territory.

“St. Clair really is the forgotten founder,” Robb said. “His home on Youngstown Ridge Road no longer exists. All that remains is a marker on Route 30 that you pass at 50 mph.

“He died penniless, which was the start of bad luck for my family for 100 years.”