Dressed in a blue suit and bow tie, Aaron Gibson looked pensive.

It was finally his turn to appear before the Pennsylvania Board of Pardons.

The regional executive director of three Pittsburgh YMCA branches — who oversaw the $7.4 million transformation of the Centre Avenue Y into housing for at-risk men and the $12 million construction of the Thelma Lovette YMCA, and who also has helped thousands of other people — was asking to have a conviction for drug sales erased from his criminal record.

To no longer be a convicted felon.

The hearing lasted only 2 minutes and 21 seconds, but it took 30 years to get there.

Serving his time

In 1992, Gibson, who grew up in Larimer, was working full time as a maintenance man. But then he lost his job, and his brother was killed in a domestic dispute.

Like so many others in his neighborhood, Gibson turned to selling drugs.

At the same time, he joined a program at YMCA of Greater Pittsburgh teaching at-risk men to build computers and how to start their own businesses.

“I wanted to try to find a way out of selling drugs, but the computer work didn’t pay enough,” he said.

He was supporting a grandmother who raised him and three children. So he kept selling.

But on June 3, 1994 — a week after he’d sold an individual 1.5 grams of crack cocaine — a drug task force showed up to search the house he shared with his grandmother in Homewood.

Gibson wasn’t home at the time, but a friend called to let him know the police were there.

“I decided to go home and tell them who I was,” he said.

When he arrived, police handcuffed him.

They found an ounce of cocaine, Gibson said, and $2,000 in a chair.

He was charged with three counts: possession with intent to deliver, possession of a controlled substance and possession of drug paraphernalia.

Gibson pleaded guilty in January 1996 and was ordered to serve a mandatory prison term of three to six years as a first-time offender.

He served about a year at SCI Laurel Highlands and then six months in a boot camp.

The worst part of incarceration, he said, was when his kids — who were 6, 3, and 2 at the time — visited.

“They couldn’t understand why I couldn’t come home,” he said. “That hurt me a lot.”

When he first arrived in prison, an older man said to him: “ ‘Young man, you don’t strike me the type of person to be in this environment,’ ” Gibson recalled.

He told the man that he would adapt.

Gibson clearly remembers the reply: “You don’t want to adapt to this environment,” the elder said. “If you adapt, you will become a part of it.”

The advice clicked. Instead, Gibson said, he decided to “adjust” to prison life — and commit to bettering himself when he got out.

Because of prison overcrowding, he was released after 18 months.

Jim Cimino, now 84, was the vice president of financial development for the YMCA of Greater Pittsburgh and ran the East End outreach program that Gibson had been a part of before his arrest.

“He’s been in my life ever since,” Cimino said.

Before prison, Gibson lived in a community where many young men sold drugs.

“It was the way these kids fed their families,” Cimino said. “They sold drugs and were into the streets.”

Still, Cimino also saw innate leadership qualities in Gibson.

“He motivated everyone around him,” he said.

Over the years they worked together, Gibson became like an adopted son, Cimino said.

He clearly remembers the day Gibson was sentenced.

“The judge said, ‘This kid should not be in jail, but I have no option but to put him there,’ ” Cimino recalled.

Throughout the 18 months Gibson was incarcerated, Cimino visited frequently. He drove Gibson home on the day of his release.

They immediately went to the central office of the YMCA and met with CEO Julius Jones. A towering man at 6 feet 6 inches tall, Jones was a larger-than-life figure.

Jones posed a question to Gibson: What do you want to do with your life? Go back to the streets or take a different path?

“ ‘You have a choice,’ ” Gibson recalls Jones telling him. “ ‘Nobody can make it for you.’ ”

Gibson chose a job at the Y working with the homeless.

“I’ve been with the YMCA ever since.”

Over the past 27 years, Gibson has served in various capacities with YMCA branches across the city.

He led the construction of the Thelma Lovette YMCA in the Hill District, which opened in 2012, and led the $7.4 million renovation of the Centre Avenue Y, which opened as Centre Avenue Housing in 2021 and provides housing for 74 men at risk of homelessness.

“Aaron truly leads by example. He won’t ask anyone to do anything he wouldn’t do himself,” wrote Carolyn Grady, the chief development officer for the YMCA of Greater Pittsburgh, in a letter to the pardons board. “I recall that when the Thelma Lovette Y opened, Aaron spent several months leading the cleaning crew to ensure they were cleaning to his standards!”

Applying for a pardon

Even though Gibson had risen through the ranks at the YMCA to become an executive and highly respected member of the community, the idea of applying for a pardon stuck with him.

“There’s still that stigma of being a felon that I knew could hurt me if I moved to a different city or applied for a different position,” he said.

Gibson also sees a pardon as a chance to show other young men of color that, even if they’ve previously gotten in trouble, they can walk the right path and clear their record.

“I am blessed to be able to do that — not only get my record clear, but it gives me a platform to be a voice for those others,” he said.

In Gibson’s work, he often hires people with felony convictions. In his capacity as a landlord, he rents to them, too.

“It’s important, because, if they’re not given an opportunity, they may go back to the streets,” he said. “When they have that scarlet letter on their jackets, that’s a part of who they are in some people’s eyes.”

In his quest for a pardon, Gibson submitted dozens of letters — from colleagues, other leaders in the Pittsburgh nonprofit community, politicians and those he mentored.

Lisa Reihl first met Gibson when she worked as a waitress in 2004. A single mom, she approached him with ideas for family programming at the Hazelwood YMCA, she wrote in a letter to the board.

They spoke one morning as Gibson continued to work and move through the facility. Gibson told her he was trying to find a program director and once he did he would be in touch.

A month later, as he was driving through the Hazelwood area, Gibson saw her walking along the street and pulled over.

“ ‘Remember me?’ ” Reihl said he asked her.

Gibson told Reihl he had hired a program director and that he’d like Reihl to come volunteer at the Y.

“I was hesitant as I didn’t have much self-confidence, but he can be very convincing,” she wrote.

Reihl began volunteering. When she lost her job as a waitress, she took a full-time job at the Y.

“This began my career at the Y, thus forever altering my path in life,” she wrote. “Mr. Gibson had faith in me.”

The letters describe him as a leader by example, driven and hardworking.

“He is overwhelmingly kind, gracious and patient,” wrote city Controller Rachael Heisler, who serves as the board chair for the Allegheny YMCA. “He works with children and seniors alike and shows everyone he meets profound respect. He is easy to get along with and, by every measure, he lives his values.”

In addition to citing his work ethic, the letters are full of references to the Thelma Lovette swim program that Gibson champions and notes he is a fantastic spin instructor — continuing to offer his “legendary” classes even during the pandemic, over Zoom.

But it is his way of showing by example, the letters said, that make Gibson a role model.

“He is neither reticent nor proud to share his personal story. Instead, he offers it freely as living proof of what can happen when someone is provided an opportunity to turn their life around,” Grady wrote in her letter. “Aaron is passionate about giving others the second chance he received so many years ago. He is a vocal advocate for former offenders and bravely and respectfully speaks out on their behalf.”

Gibson has been married to his wife, Kelretta, for 16 years. They have two sons, 16 and 11.

He credits his family as being a major source of support in his drive to impact the community.

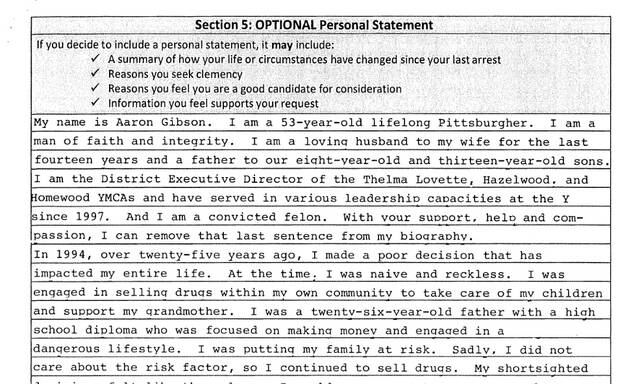

“In order to take the next steps in becoming the best husband, father and man I can be, I am seeking a pardon,” Gibson wrote in his application. “I will always regret my actions from 1994 and the pain that they caused. I am asking for a clean slate so that I can continue my journey to being the best man I can be and having the greatest impact on the most amount of people.

“I have worked tirelessly these past 27 years, and I will never stop working.”

The hearing

Gibson’s hearing Wednesday, like the others who go before the Board of Pardons, was held virtually. His was one of 36 scheduled for the day.

Gibson attended with his attorney, Scott Scheinberg, from the Jones Day law offices in the BNY Mellon building on Grant Street. The firm represented him for free.

“Aaron is exactly the type of person who deserves a second chance,” Scheinberg told TribLive. “For the past 30 years, he has dedicated his life to bettering the community, and he has succeeded.”

As the hearing began, board member Marsha Grayson, who serves as the victim representative and is from the Pittsburgh area, abstained from participating.

Pardons board members Dr. John P. Williams and Lt. Gov. Austin Davis told Gibson they had no questions.

Harris Gubernick, a corrections expert, asked how long Gibson sold drugs before his arrest, how he was caught and whether he’d ever been revoked while on probation for the four years afterward.

He had not.

Attorney General Michelle Henry asked how long Gibson served in prison and what he’s doing now.

And that was it. Gibson did not get the chance to recount all he has done in the three decades since his arrest.

Maybe he didn’t need to. A few hours later, the board voted unanimously to recommend Gibson for a pardon.

It now will be up to Gov. Josh Shapiro to either approve or deny the recommendation.

Last year, 395 pardons were recommended by the board. The governor granted 137 of those and denied 10.

The rest remain pending.