Todd Caddy is the man behind the mirrored glass at Pittsburgh’s front door.

His job: tunnel manager for PennDOT.

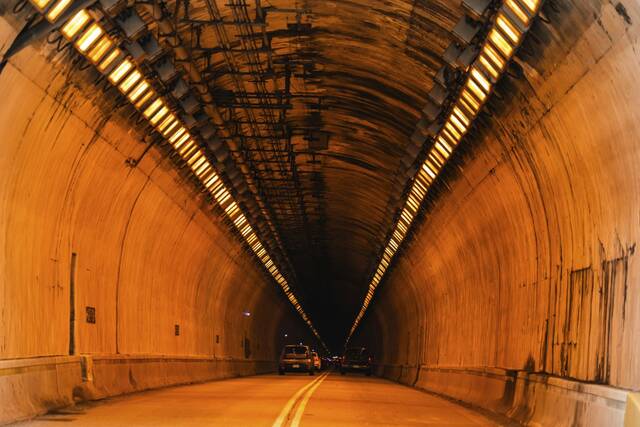

From his office on a recent weekday morning on the south face of Mt. Washington, Caddy watched as two lanes of cars and trucks approached, slowing as they descended Green Tree hill and entered the Fort Pitt Tunnel. If he turned around, he could see another two lanes of traffic headed out of the tunnel, accelerating to climb the hill away from the city.

From his computer, he also monitors happenings at the Squirrel Hill and Liberty tunnels, as well as the roads and bridges leading to and from each of the tunnels. PennDOT also maintains the shorter and less traveled Stow Tunnel nears McKees Rocks.

Caddy’s office is the central nervous system of the tunnel systems, where he oversees 75 workers who keep the tunnels open and respond to people in distress, whether because of a crash or a mechanical problem.

Caddy, 60, of Carnegie started as a snowplow driver in Monroeville. Since 1999, his office space has been the tunnels of Pittsburgh.

“The uniqueness of this job makes it special to me,” he said.

Pittsburgh’s array of tunnels are a keystone of its infrastructure and one of the things that set it apart from other cities. The tunnels in places like New York City and Boston are part of the complex transportation network of a metropolis. But in Pittsburgh, the tunnels create a grand entrance to the city that is unrivaled and recognized as something special.

The feeling was chronicled in a January 1988 essay about Pittsburgh in the Sunday New York Times by architecture critic Paul Goldberger that proclaimed:

“This is the only city in America with an entrance. You slide and slither into most downtowns, passing through gradual layers of ever-more-intensely built-up sprawl, and you do not so much enter the center as realize after you are there that it is all around you. Not Pittsburgh. Pittsburgh is entered with glory and drama. If you come to Pittsburgh from the airport, you do not see the city as you approach it. You see hills and valleys and the minutiae of suburbia, but no city. Suddenly the expressway dives into a tunnel through Mt. Washington — and on the other side, revealed all at once, is a skyline of striking power.”

The dramatic entry remains memorable to Goldberger now and he’s enjoyed several return visits, he told TribLive.

“It creates something that has a drama that exists in no other city in this country or the world for that matter,” Goldberger said.

In addition to the Times, Goldberger’s prose has graced the pages of The New Yorker, and he’s also written several books about cities and the beauty of their architecture, along with an appreciation of baseball stadiums, “Ballpark: Baseball in the American City” that was published in 2019.

Entering Pittsburgh from the Fort Pitt Tunnel seems like it was choreographed, Goldberger said, although there’s no evidence the design was intentional.

Inside the nerve center of the tunnel system

Inside the south end of the Fort Pitt Tunnel, PennDOT’s nerve center offers a view of traffic entering and leaving the city.

In the office behind the glass and in another workspace at ground level, Caddy and other PennDOT workers monitor the tunnels along with the traffic patterns on the Liberty and double-decked Fort Pitt bridges. The crews also drain the bathtub section of the Parkway East when the Monongahela River floods.

Each tunnel has two bores at each end, and the tubes are connected by those cross passages noticeable for their numbered doors: seven in Fort Pitt, eight in Squirrel Hill and 11 in Liberty.

“It’s a safety exit from one side to another,” Caddy said.

Four-person crews staff each tunnel around the clock. They have their own tow trucks and use cameras to monitor what’s happening inside and outside the tunnels and on the bridges.

If and when something happens, they’ll likely know about it even before the driver calls for help, Caddy said.

The best thing to do is pull over and wait for help to come, he said.

“We’ll get you out of there safely,” he said.

Each week, PennDOT responds to an average of 36 incidents at the Fort Pitt Tunnel, 34 at Squirrel Hill and 12 at Liberty.

The crews also track the air quality inside the tunnels, wash the insides and replace the more than 14,632 sodium vapor light bulbs (Fort Pitt: 3,576; Squirrel Hill: 4,624; Liberty: 6,432) that rack up an electric bill that totals nearly $1 million per year.

The ventilation systems for the Fort Pitt and Squirrel Hill tunnels consist of heavy-duty exhaust fans that pump fresh air into the tunnels as needed.

The Liberty Tunnels use a ventilation system atop Mt. Washington that consists of four brick chimneys and fans that remove exhaust fumes and replace it with fresh air. The system was recognized Sept. 4 as a National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark because it was the first of its kind in the nation. Its design influenced the Holland Tunnel in New York and Boston’s tunnel system.

A carbon monoxide alert will sound when the level is 35 parts per million — exponentially smaller than the 800 ppm at which point it becomes dangerous to people, Caddy said.

There are no fumes in his office, and atop the roof of the Fort Pitt Tunnel it’s windy from the fans and the traffic whirring. From above, the lanes look wider than they do from inside a vehicle, and the traffic blurs past, echoing off the roof.

The Squirrel Hill and Fort Pitt tunnels are similar in design.

The region’s other tunnels include the Armstrong, Cork Run, Corliss, Mt. Washington Transit, North Shore Connector, Pennsylvania Canal, Pennsylvania and Castle Shannon, Pennsylvania and Steubenville Extension Railroad, Schenley and Wabash.

The tunnels pair with the city’s bridges and roads to connect Pittsburgh’s 90 neighborhoods and Allegheny County’s 130 municipalities with the rest of the region.

“We had to drive around these hills before we had the tunnels, and that was a long trip,” said Arthur Ziegler, who has been active with the Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation for 50 years. “When I was a kid, it was a big experience to be able to walk through the Liberty Tunnels.”

The sidewalks were removed in the 1970s when the lanes were widened.

Gatekeeper

“The tunnels are somewhat the gatekeeper between us and the city,” Mt. Lebanon Commissioner Jeff Siegler said.

Siegler is an urban planner who worked as the coordinator for Ohio’s Main Street program that helps downtown areas. He’s founder of Revitalize or Die, a consultancy that offers advice to foster civic pride.

He grew up in Lima, Ohio — a section of the Buckeye State that’s “flat, brown and not real pretty,” he said.

He settled in Mt. Lebanon about a decade ago. He said he loves Pittsburgh, and the city’s topography and layout appealed to him.

The tunnels make entering Downtown special, Siegler said, echoing the sentiments of others that include regional historian and architectural expert Mark Houser.

Houser can quote Goldberger’s description of the city verbatim.

“It’s a fantastic (opening), and it’s true,” Houser said. “I’ve brought many visitors to Pittsburgh, and I always make sure to bring them first through the Fort Pitt Tunnel because there is nothing to compare to it, and it never fails to astound and delight.”

A former TribLive journalist and Robert Morris University spokesperson, Houser is an architecture and history buff who has written several books, including “MultiStories: 55 Antique Skyscrapers & the Business Tycoons Who Built Them” and “Highrises Art Deco: 100 Spectacular Skyscrapers from the Roaring ’20s to the Great Depression.”

He leads tours of notable buildings in cities across the country, including Pittsburgh.

South Hills-bred writer and filmmaker Stephen Chbosky also used the Fort Pitt Tunnel to dramatic effect in his 1999 novel “The Perks of Being a Wallflower.”

The 2012 film, also directed by Chbosky, gave those who have never been to Pittsburgh a chance to see its dramatic entrance.

Chbosky and his agent didn’t respond to interview requests.

Breaking through the hills

The shortest distance between two points is a straight line, and it took tunnels bored through Mt. Washington and Squirrel Hill to connect the South Hills and eastern suburbs with the city’s Central Business District and foster growth across the region.

At the 1920 census, Mt. Lebanon’s population was about 2,200. By the 1930 census, the population surged to more than 13,400.

“There couldn’t be a Mt. Lebanon without the Liberty Tunnel,” Houser put it.

Siegler agreed and said the area likely would have remained farmland without the access to the city the tunnels provided.

“I’d say for all that we complain about our tunnels, they are such a unique and iconic part of Pittsburgh that it would be a tragedy if we didn’t have them,” Houser said.

The only comparable view in the U.S. is upon exiting the Wawona Tunnel at Yosemite National Park in California, Houser said.

But El Capitan, Half Dome and Bridalveil Fall are all natural landmarks, while the Pittsburgh cityscape was mainly forged by the blood and sweat of the region’s industrial workers.

“Do they slow our traffic down? (Yes.) This is the price we pay for such a glorious feature,” Houser said. “Cleveland wishes they had a tunnel this cool.”

By The Numbers, tunnels

Fort Pitt

Length: 3,614 feet

Opened: 1960

Daily traffic: 108,240

Light Fixtures: 1,788

Bulbs: 3,576

Annual power bill: $284,000

Cross passages: 7

Squirrel Hill

Length: 4,225 feet

Opened: 1953

Daily traffic: 106,799

Light Fixtures: 2,312

Bulbs: 4,624

Annual power bill: $322,000

Cross passages: 8

Liberty

Length: 5,889 feet

Opened: 1924

Daily traffic: 66,232

Light Fixtures: 2,952

Bulbs: 6,432

Annual power bill: $202,000

Cross passages: 11