A grassroots group of scientists and researchers has brought together more than 31,000 volunteers worldwide — including from Western Pennsylvania — who are willing to take part in a human challenge trial to test potential covid-19 vaccines.

A human challenge trial in this case would involve participants being administered a candidate vaccine and then deliberately exposed to the coronavirus in a controlled setting, where they are monitored by medical professionals.

The idea is to faster test a potential vaccine’s effectiveness and ultimately speed up production.

“Our goal is to advocate on behalf of these volunteers,” said Abie Rohrig, a spokesman for 1 Day Sooner, a nonprofit recruiting people willing to participate in challenge trials.

One such volunteer is Ellen Kiley, 49, of Forest Hills.

“I was interested because there’s not really a lot I can do to help in this pandemic, other than be a good citizen and try to help my friends and neighbors,” Kiley said.

1 Day Sooner was co-founded by Josh Morrison and Sophie Rose. Morrison is the executive director for Waitlist Zero, a nonprofit that seeks to reduce wait times for kidney transplant patients and streamline the transplant process. Rose is pursuing a master’s degree in infectious disease epidemiology at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore.

Through Waitlist Zero, Morrison had advocated for living kidney donors. During the pandemic, he read an article that proposed the idea of accelerating vaccine development by deliberately exposing volunteers to the coronavirus.

No shortage of volunteers

“Josh thought, ‘Would anyone actually do this?’ ” Rohrig said.

In short, yes. A lot of people.

“Pretty soon after he launched the 1 Day Sooner website, more than 1,000 people had signed up,” Rohrig said. “Now there are more than 31,000 volunteers from 140 countries.”

Volunteers are not set to undergo a human challenge trial, but 1 Day Sooner is seeking those opportunities.

“We’re not involved in the production of any vaccine,” Rohrig said. “Our job is to advocate and connect volunteers with challenge trials, should they arise.”

Volunteers like Kiley would be administered a vaccine that has gone through the first two phases of testing, which focus on the vaccine’s safety and gauge the immune response.

“Challenge trials can happen in conjunction with Phase III trials, which are the big field studies for a vaccine, which can take anywhere from six months to a year,” Rohrig said.

In trying to balance risk and reward, volunteers should be younger and in good health, Rohrig said.

But the inherent risk is clear to volunteers like Kiley.

“It would be silly to say that I’m not concerned,” she said. “But I trust the people who are designing the trials are going to make it as safe as it can be.”

Rohrig isn’t just seeking volunteers — he is one.

“If challenge trials can accelerate vaccine development, volunteers are ready and willing to take that risk,” he said. “I’m one of them.”

Thomas Smiley, a volunteer from Cincinnati, said he hopes a human challenge trial will allow for a concentrated study of a potential vaccine.

“I understand the reservations associated, ethically and fiscally, about signing off on such a study, but it does not go without precedent. Human challenge trials have been used in the past for a number of infectious diseases with great success,” Smiley said.

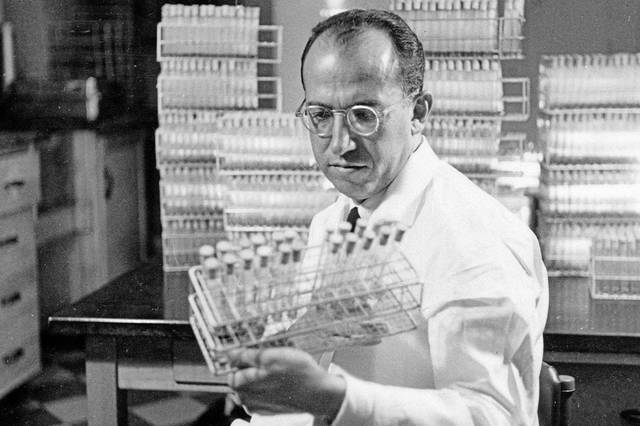

Salk’s shadow

Human challenge trials played a critical role in the battle against diseases like smallpox, cholera and malaria. Others, including Dr. Jonas Salk, have experimented on themselves to speed along medical discoveries.

In May 1953, Salk came home from the University of Pittsburgh and boiled some needles and syringes on the kitchen stove in his Pine Township home. His family — notably himself and his three sons — were among the first humans to get a test shot of his still-experimental vaccine against a mysterious virus crippling and killing children worldwide.

“I’m sure that my father told us (the importance of) what was happening,” said Dr. Peter Salk, a Pitt professor of infectious diseases and microbiology and president of the Jonas Salk Legacy Foundation.

Now 76 and living in California, he was 9 at the time.

“I … was just not happy at the notion of having another shot,” he told the Tribune-Review in April. “The point of that was to demonstrate my father’s confidence in the vaccine. But … it was also, from my father’s side and my mother’s side, ‘Let’s get these kids protected.’ ”

In 1954, nearly 2 million children received Salk’s polio vaccine candidate. By 1955, the pivotal public health experiment was deemed a success, with the vaccine proving to be safe, potent and 90% effective.

Marla Kruth of Hampton was one of the early ones to receive the vaccine.

Now, she has volunteered to be screened for vaccine trials through UPMC and the University of Pittsburgh. Researchers are seeking at least 750 people in Western Pennsylvania to take part locally in what is being called Operation Warp Speed, a national push to rapidly develop a vaccine that’s safe and effective.

“My mom was at Pitt when the Salk (polio) vaccine was announced, and I was part of the first generation to receive that vaccine, and I think it’s really cool to have research being done in Pittsburgh for something so important and so big,” Kruth said. “I want to do my part, is the way I’m looking at it.”

Risking uncertainty

1 Day Sooner sent an open letter to the National Institutes of Health advocating for human challenge trials, with signatories including medical professionals worldwide and Nobel laureates.

The letter urges the NIH “to undertake immediate preparations for human challenge trials, including supporting safe and reliable production of the virus and any biocontainment facilities necessary to house participants.”

In May, the World Health Organization published guidance supporting human challenge trials — if done ethically. In June, WHO published a draft laying out a practical roadmap for implementing such trials.

There are no human challenge trials scheduled, but Rohrig said he is hopeful the first might be feasible within months.

“I understand there’s a lot of uncertainty with the long-term risks of covid-19,” he said. “But I and others are willing to take that risk, because we think the potential reward is so great.”