Therese Rocco, a devout Catholic, Pittsburgh native and trailblazing police officer who became a role model for women and embraced the saintly task of tracking down missing children as her life’s work, died Monday after several weeks in hospice care at West Penn Hospital. She was 97.

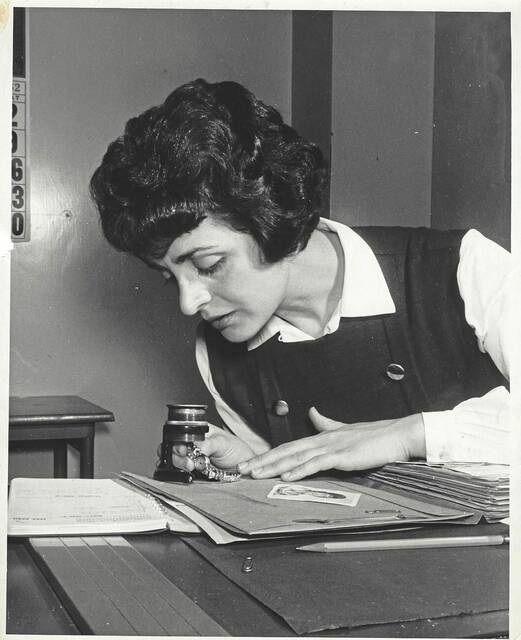

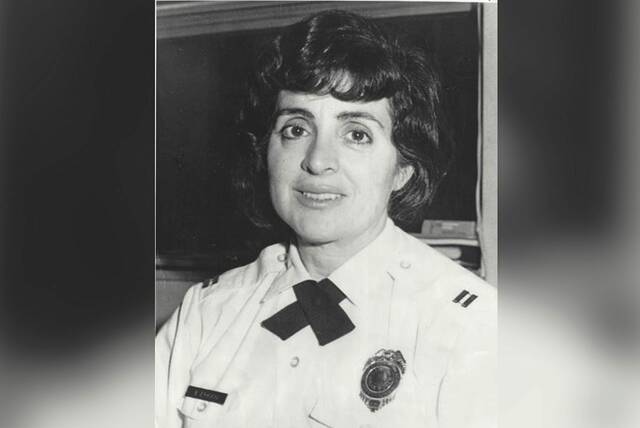

Diminutive and dogged, compassionate yet steely, Rocco became the first female assistant chief in the Pittsburgh Bureau of Police, steadily rising over a career of more than a half-century from a clerk in the missing persons bureau to the captain of the squad and ultimately one of the department’s highest-ranking leaders.

Along the way, Rocco worked countless missing persons cases, becoming known for her relentless perseverance and time spent working with bulldog tenacity in her off hours. She never married and had no children, though she said that she considered the missing youngsters her kids.

Long after her retirement, she remained a go-to resource for detectives eager to crack cold cases and reporters seeking information whenever tantalizing developments emerged. She would invariably invite inquisitive newshounds to stop by her house on Berkshire Avenue in Brookline, where she shared information stored in reams of personal files and her prodigious memory.

Related:

• 2020: '70s saw beginning of change for women in Pittsburgh police ranks• 2018: Answers still sought for 'lonely child' who disappeared from Pittsburgh in 1962

Beyond the success of reuniting so many missing children with their families, Rocco’s crowning achievement might arguably have been leading the charge to shatter the glass ceiling in Pittsburgh’s police bureau and buoying generations of aspiring female officers. She didn’t just survive in a man’s world; she excelled in it and proved to others it could be done.

One person who fell under her spell: Ophelia “Cookie” Coleman, Wilkinsburg’s longtime police chief, who served for decades as a Pittsburgh police detective.

“That’s what I call her, the legend, because Therese was a beacon of light that we younger, newer police women looked up to. We were rooting for Therese because we knew that if Therese made it, she would see to it that we would make it as well,” Coleman said. “She was about equality. She didn’t go for that, ‘We can’t do this because we have on a skirt.’ She felt that we had what it took to do the job, and she proved that each and every day that she came to work.”

Coleman’s squad room and Rocco’s were next to one another, separated by an open doorway. Coleman had easy access to the person who at the time, in the 1980s, stood out from literally every other city police supervisor because she was a woman.

“Working with her you got an up-close, front-seat view of what to do and how to do it,” Coleman said. “She had a work ethic that was second to none. She came in early in the morning and sometimes she wouldn’t leave until the next day.”

Rocco was the daughter of Italian immigrants who settled in the Hill District on Wylie Avenue. Her father worked for the railroad; her mother ran a boarding house, washed people’s laundry and did odd jobs. Rocco, the third of four children, grew up speaking Italian and would translate her mother’s broken English.

She graduated from a Catholic high school and went to the University of Pittsburgh. Her nephew, George Moneck, a retired priest in the Pittsburgh diocese, recalled his aunt telling an interviewer that she didn’t want to be a police officer. But at age 18 she was offered a position as a clerk typist with the Pittsburgh police.

“They’d ask her if she would help on a certain cases they were doing, and it just evolved from there,” Moneck said.

Evolution meant working as a decoy and assisting in prostitution stings – an unusual career choice for a woman who attended daily Mass and eschewed four-letter words. She stood – all 5 feet of her – as an equal to her rough-and-tumble male colleagues. Coleman recalled that Rocco could hand out zingers with the best of them and didn’t hesitate to give as good as she got, even if she kept it clean.

Moneck remembers hanging around his aunt as she worked her cases, mostly getting on her nerves, but watching with fascination as events that would sometimes make the news played out in the apartment upstairs from where he lived with his mother, Rocco’s sister.

“I think her faith got her through all of it,” Moneck said. “I used to call her Mother Teresa of Brookline.”

Rocco became a familiar figure in the neighborhood. She would walk all over it, lost deep in thought, likely about a case.

“The more she walked, the more she was thinking about her cases, I’m sure. She walked into a phone pole one time and she almost got hit by a car. Her mind was going a thousand miles an hour,” Moneck said.

All that exercise kept her fit – and kept her from behind the wheel. Rocco had a reputation as a lousy driver.

“She was tiny, but she had a shape that would knock out anybody,” Coleman said.

One former Brookline resident, also a police officer, remembered Rocco’s jaunts. She sometimes stalked Brookline Boulevard in high heels or wrapped up in a leopard-skin coat in the winter, recalled Catherine McNeilly, a longtime colleague.

McNeilly, a former police commander whose husband, Robert, was Pittsburgh’s chief for a decade, vividly recalled her earliest encounters with Rocco some 50 years ago.

Rocco was teaching a law enforcement class at what was then Carlow College, and McNeilly was a student. She was starstruck.

“I sat in the front row and was just enamored with every single thing about her – her looks, her knowledge, her voice, everything, and thought, ‘I want to be just like her.’ ” McNeilly said Tuesday. “I just looked at her, and I was in awe.”

Rocco and her ascent in a heavily male-dominated profession proved to a generation of young women that they had the mettle to work in policing. And Rocco was happy to share her wisdom, McNeilly said.

“Aside from every other wonderful saintly quality about her, the best thing about her was she never hesitated to hold women up,” McNeilly said. “I mean, sometimes we’re our own worst enemies, and we can hold other women down from getting ahead. But not her. Whatever she could do to lift you up she did.”

Rocco carved out a niche as an expert in missing persons. She became an authoritative figure who received honors and accolades.

William P. Mullen, Allegheny County’s former sheriff, worked with Rocco during his 37-year career with the city police, from which he retired as deputy chief. He said that she developed a potent network of sources and helpers as she strove to make the missing reappear. Being smart, gregarious and personable helped. She easily made friends among the various detective squads, he said, and was always willing to lend a hand.

It was no surprise that when it came time to promote Rocco, she was elevated to assistant chief by two other pioneers – Sophie Masloff, Pittsburgh’s first female mayor, and William H. “Mugsy” Moore, the city’s first Black police chief.

Women on the job paid attention.

“We loved the way she walked, we loved the way she talked. It was women watching her,” Coleman said.

“You learned a lot about what to do, what not to do, how to dress, how not to dress. Hair always immaculate, manicured to a T, clothing, she was just impeccable. And she was educated, she was very intelligent. She didn’t have to raise her voice.”

During a storied career that brimmed with success stories, Rocco also had a few failures.

The one that might have gnawed at her the most: the 1962 disappearance from Bloomfield of 10-year-old Mary Ann Verdecchia. Her remains have never been found.

“Until the day she died, she was wanting to solve that case,” Moneck said.

Another case that hit Rocco close to home involved the 2018 discovery of human bones in a backyard in Pittsburgh’s Garfield neighborhood. They belonged to Mary Arcuri, who had disappeared in 1964.

Arcuri and her husband, Albert, had been the Roccos’ friends and neighbors in the Hill District; Rocco was their daughter’s godmother.

Albert Arcuri, who died in 1965, had told people that his wife had left him. Police weren’t called, no missing persons report was filed. In 2019, Rocco said in an interview that she had always doubted Albert’s story.

Rocco’s legacy led the police bureau to name a conference room after her in 2009. She released a memoir in 2017. And two years later, a documentary about her debuted.

“She changed the whole landscape of policing,” Coleman said. “She was Pittsburgh’s treasure.”