Activist's fight against segregation evolved into political action to push for voting rights

NEW YORK — Norman Hill was at the AFL-CIO office in Washington, D.C., in August 1965, and recalls cheering when he learned the Voting Rights Act had passed Congress. He then took a moment to remember the people “who were killed, literally, struggling to try to get Blacks registered to vote.”

Now 90, Hill started working in the Civil Rights Movement with the NAACP in Chicago before joining the Congress of Racial Equality in the early 1960s to work on its Route 40 Project.

Route 40 was the major corridor between Washington, D.C., and New York, but many restaurants along the highway in Maryland and Delaware served whites only. CORE staged sit-ins and was preparing a massive motorcade to fight the practice when several restaurants relented and desegregated.

That prompted the Maryland Legislature to pass a public accommodations law in 1963 banning discrimination in hotels and restaurants, becoming the first state below the Mason-Dixon Line to do so.

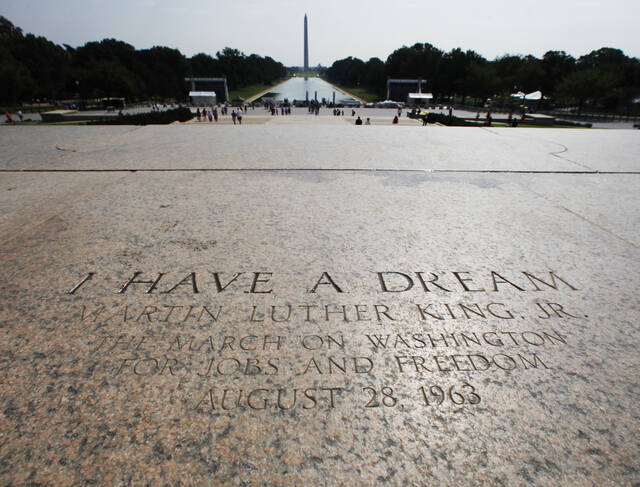

Hill then helped coordinate the March on Washington, where Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his historic “I Have a Dream” speech. Afterward, he decided it was time to change tactics.

“I left the Congress of Racial Equality in 1964 because I felt a transition needed to be made in the civil rights movement, from an emphasis on protests to engaging in political action,” he said.

He joined the industrial union arm of the AFL-CIO as its civil rights liaison and legislative representative, becoming involved in raising the minimum wage and working with the labor delegation on the Selma-to-Montgomery voting rights marches.

Related: Voter Rights Act Voices

• Voting activist killed during Freedom Summer in Mississippi believed country should be integrated

• Andrew Young was at Martin Luther King’s side throughout often violent struggle for civil rights

• Young lawyer who helped write voting rights bill ‘star-struck’ as he witnessed 1965 signing into law

• Voices from the violent civil rights era see attacks on voting rights as part of ongoing struggle

• Voting rights marcher recalls being clubbed, hearing fatal gunshot during pivotal day of protests

• LBJ’s daughter Luci watched him sign voting rights bill, then cried when Supreme Court weakened it

Hill said labor leaders were particularly interested in the voting rights struggle because they thought their own union movement would benefit from increased Black participation in the political process.

“The trade union movement thought that perhaps Blacks having their right to vote and actually voting might change the political climate in the South, where unions had struggled to organize because the South was not only anti-Black, but anti-labor,” he said.

There had to be mechanisms for registering, he said. Before the Voting Rights Act became law, Hill said Black residents in the South who tried to register faced tests, such as “how many bubbles are in a bar of soap or interpret a section of the Constitution.”

“And no matter how clear the interpretation was, Blacks were denied the right to vote by the registrar,” he said.

He did not anticipate, nearly 50 years after it was signed, the Supreme Court in 2013 striking down as unconstitutional the way states were included on the list of those needing to get advance approval for voting-related changes. The ruling was based on a conclusion that labeling states as discriminators by relying on information half a century old was not supported.

Now the country awaits a Supreme Court decision on whether the Voting Rights Act will be reinforced or further eroded.

If he could speak to the justices, Hill said he would tell them the ability to cast a ballot is the foundation of the country.

“Without the right to vote, the political process — and in fact the democratic reality — was not one that blacks could experience,” he said.

Remove the ads from your TribLIVE reading experience but still support the journalists who create the content with TribLIVE Ad-Free.