Last week’s initial jobless claims, which tally up the number of people applying for unemployment benefits for the first time, were horrifying. The numbers present bad news and worse news. But if we can see through the devastating haze that is our economy, there might be some good news on the horizon, even if this is accompanied by a warning.

First, the bad news. This week’s initial jobless claims, 6.6 million, were twice last week’s of 3.3 million, which were 15 times the typical 225,000.

Unemployment numbers only come out once a month, and we won’t get the next batch of numbers until mid-April. But combining last month’s unemployment numbers with the past two weeks’ initial jobless claims paints a pretty clear picture of where we are right now. Unemployment is likely around 9%, which is just shy of its 10% peak during the 2008 recession.

And now the worse news. Pennsylvania was better than most states at getting laid-off workers on to the unemployment rolls. That’s part of why Pennsylvania is showing the second highest per-capita initial jobless claims in the country. Adding Pennsylvania’s initial jobless claims to its unemployment rate from last month puts the state’s current unemployment rate at around 17%. That’s Depression-level unemployment, and we’re likely to see numbers closer to this for other states as they process their own deluges of unemployment applications.

After all this, there is some good news. Because while we are looking at Depression-level numbers, we might not be looking at a depression. The difference between a depression and a recession is not just the magnitude of unemployment, but also the duration. The Great Depression lasted for a decade. Much of the unemployment we have today could be reversed instantly simply by allowing businesses to reopen. Most of the jobs people lost are still there, waiting for the workers to return.

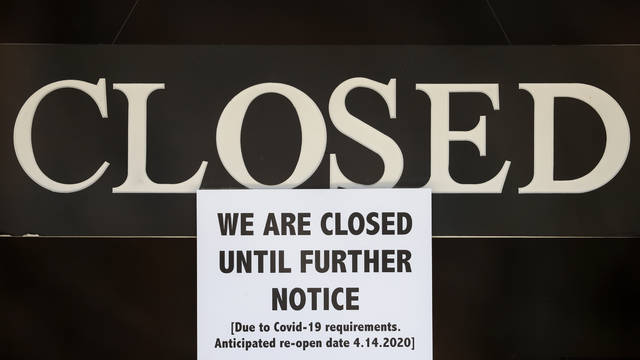

But herein lies the warning. Those jobs won’t wait forever. The longer we require businesses to remain shuttered, the greater is the probability that those businesses will remain closed permanently. And when they close permanently, the jobs will disappear.

Of course, the point of closing businesses is to prevent the virus from spreading and killing more people. But the longer businesses remain closed, the more deaths we’ll suffer from poverty, mental illness, domestic violence and any number of other things, all exacerbated by a prolonged economic downturn. We must be extremely careful that our solution for dealing with the virus doesn’t become more deadly than the virus itself.

And therein lies the rub. People seem to think that politicians can simply pull a lever and flip a switch and bad things will stop happening. What they need to realize is that politicians can only stop some bad things from happening, and in so doing, cause other bad things to happen. We live in a world of trade-offs, and it’s time to start asking which trade-offs are worth making. Epidemiologists offer one set of answers. Economists will offer another, social workers another still.

And however we ultimately decide to act in the face of covid-19, it’s time now to admit the complexity of the problem, and to start counting all the costs across all the ledgers.